In the above excerpt from Food Systems, Chapter 4: The System, Dr. Mindy Fullilove, Dr. Eva-Maria Simms, Brian Brown, Karen Abrams, Celeste Taylor, and Felicia Lane Savage discuss the trajectory of the Hill District, from a vibrant cultural center to a decimated community.

![]()

In many American cities during the 1940s, amid a spirit of modernism and under the banner of progress, urban planners initiated revitalization efforts in high-density, low-income neighborhoods. But instead of investment, “urban renewal,” as it’s known, delivered the demolition of buildings, housing blocks, and entire communities.

“Communities are the foundation of everything,” Dr. Mindy Fullilove, author of Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It, has said. “And when we have policies that rip apart communities, we destroy our society—and we have had such policies for many decades. … Many people agree that what [the directors of urban renewal] were doing was destroying the growing political power of Black people living in these neighborhoods.”

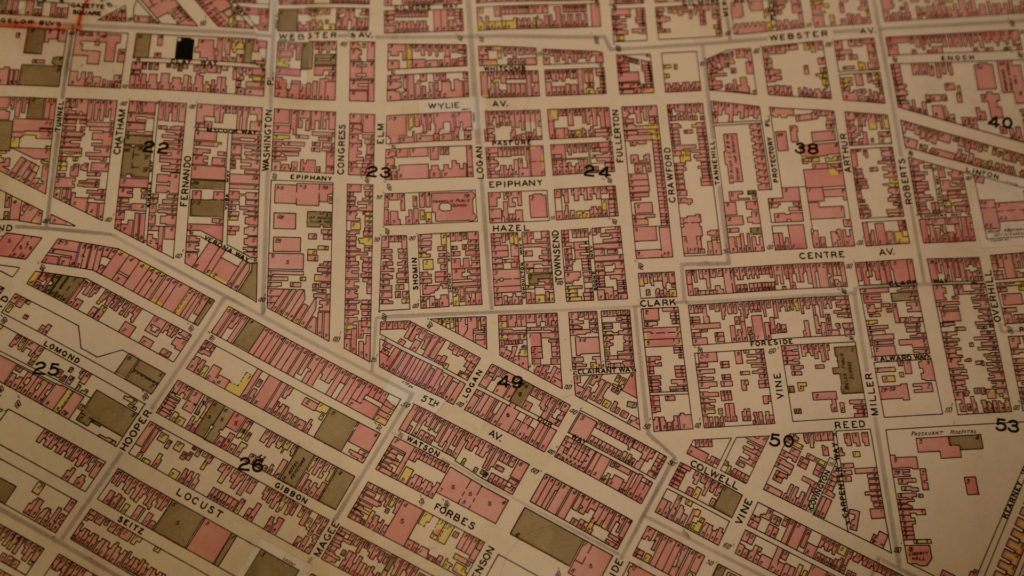

Pittsburgh went all in on urban renewal in the mid-1950s, initiating massive demolition and construction projects in the Hill District, East Liberty, and the North Side. In the face of institutionalized racist policies—one prominent example being redlining, the practice of denying services like real estate financing, public health resources, or even a car loan to residents of certain areas based on their racial or ethnic composition—these communities were nonetheless able to build vital cultural centers with strong social networks. Urban renewal broke those social bonds. To make way for the Civic Arena and a tangle of highways in the lower Hill District, 1,300 buildings were demolished in 1956, displacing 8,000 residents.

In a sense, the Hill District never recovered from the impacts of urban renewal. And with broader widespread deindustrialization, the neighborhood’s population continued to decrease, gutting its commercial core; over four hundred business closed or relocated as a result. “In the absence of industrial jobs,” Dr. Fullilove recounts, “drugs are coming in and becoming the great new employer. Under those conditions, there’s a violence outbreak, and people are driven further apart.” Yet, community activist Brian Brown adds, “Now you are telling people … to go to school, get a good education, and you’ll get a job. We know for a fact that that is not happening. How can we afford education if we’re not making enough money? It’s this generational cycle of poverty that we find ourselves in that the city is not talking about.”

Yet there remains a strong core of activists working to revitalize the neighborhood from within the community. The Hill House Association is a stronghold that promotes the cultural and artistic history of the Hill District, provides an alternate path towards a high school diploma through their Hill House Passport Academy Charter School, and directly assists older residents with finding housing, careers, and clothing. The Ujamaa Collective are a group of women building sustainable channels to sell locally-made goods, promoting entrepreneurship for women of African descent and the creation of infrastructure that circulates this activity and wealth within the community. And the Hill District Consensus Group is an umbrella organization that advocates for economically and racially just community development, having been involved in negotiations regarding the site of the former Civic Arena.

This video segment is an excerpt from Food Systems, Chapter 4: The System.