“Free countries are great, because you can actually sit in somebody else’s space for a while and pretend you’re a part of it. You can sit in the Plaza Hotel and you don’t even have to live there. You can just sit and watch the people go by.” —Andy Warhol

Are you here to see Pittsburgh, or just each other?” We were in the front office of the Fort Pitt Motel, a one-story motor inn tucked among the green lawns and postwar houses of small-town Oakdale, just west of Pittsburgh. It was our first visit to the city, and we were checking it out for a possible relocation. Our guidebook had mentioned nothing about the heart-shaped jacuzzis or the “Little Taste of the Poconos,” only that this was a clean, independent motel that ran $30 a night. Our own room was unassuming enough, with Tudor-style walls and a 25-cent mattress massager. The huge, healthy pine tree in the center of the gravel parking lot made me feel like I was “somewhere else,” some remote Appalachian cottage I’d never imagined. When a Port Authority bus drove past the motel through the otherwise residential enclave, my impression flipped again.

“The best thing about downtown Pittsburgh is the suburbs!” The woman checking us into the Fort Pitt was a cranky character, but once we moved here (a decade ago now) we started to notice these aspects of her character were not so unique. There was something of a simultaneous pride in, and defensiveness about, Pittsburgh. The natives thought it was the best city in the world but were almost unanimously skeptical that we would decide to move here. We did so for no binding reason—no family, no jobs, not for school, not even because we had friends here. Even the temp agent in her matching separates couldn’t believe we’d come “out of the blue”: “No one moves here, they just move back here.” But there have always been people passing through.

The Fort Pitt Motel should not be confused with the Fort Pitt Hotel, once one of the most renowned guest houses of downtown. Built in 1905 in purposeful proximity to the train station, in the days when passenger trains were at their peak, the 12-story hotel hosted fancy guests and well-heeled locals. There were numerous dining rooms of elaborate decor: the Empire Room, the Rose Room, the Vine Room, the French Room, and the celebrated Norse Room, a lower-level dining hall covered entirely in painted clay tiles, from the floor, to the ribbed, vaulted ceilings, to the murals depicting Viking sea sagas. In 1916, sleeping quarters were priced at $1.50 a day “and up,” and the hotel operated like most on the “European plan,” billing room charges separately from meals. A few Pittsburgh hotels, like the sprawling Hotel Kenmawr in Shadyside, offered the “American plan” of one all-inclusive price.

The Fort Pitt Hotel went into a post-war decline once the automobile took over, but the establishment had a long second life as a fleabag frequented by horse betters, card players, newspapermen, and a man named Art Rooney. Before he was The Chief, Rooney, who spent a good portion of his life in American or Mexican hotel rooms studying daily racing forms, and his partner Barney situated their Rooney-McGinley Boxing Club headquarters in a first floor suite at the Fort Pitt. Their cronies visited at whim, walking in through the eight-foot-high windows which met the sidewalk at 10th Street and were always wide open in the summer.

Does anyone recall that welterweight sensation Sugar Ray Robinson may have been the first African-American guest to cross the unspoken color line of Pittsburgh’s downtown hotels? His peers stayed at Bailey’s Hotel in the Hill District and trained at the Centre Avenue YMCA, but Robinson insisted that Rooney twist arms to get him into the Fort Pitt while he thrilled successively larger boxing crowds three times during three separate visits in 1946.

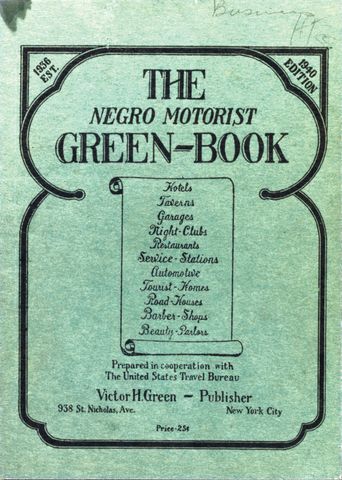

To be sure, segregation restrictions were once common in the hotel business here in Pittsburgh and across the U.S. African-American travelers in the Jim Crow era often relied on the annual Green Book to steer them to hotels and other businesses that welcomed their patronage instead of shunning it. The Green Book listed Hill District hotels and rooming houses on its short roster of friendly Pittsburgh accommodations, like The Avenue Hotel, The Ellmore, the Flamingo, and the Ellis Hotel, where Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington slept. The University Club in Oakland had modest rooms available for any university graduate—unless they were Jewish, a woman traveling without her husband, or not white. The handsome Concordia Club on O’Hara Street welcomed Jewish businessmen but did not admit women until the 1970s. Many small, no-frills hotels were “stag” back in the day, from Cousin Harry’s Stag Hotel on Smithfield, to the Stag Hotel on the North Side, to the Ship Hotel, a riverboat that docked on the North Shore of the Allegheny and offered “cool, clean rooms” for “gentlemen only.” Two YMCAs were opened in the late 1800s for boarding white working women, but a (separate) YWCA boarding facility for African-American women didn’t open until 1920.

“Here’s to our wives and sweethearts, may they never meet in Murphy’s Stag Hotel.” —A toast, circa 1914

The second time we stayed at the Fort Pitt Motel, it was on a mission to secure an apartment for our impending move. This time, our room had mirrors on the ceilings, and I was sick with strep throat and laryngitis. Of all the old Pittsburgh apartment buildings we toured, the one that charmed us the most was a former “apartment hotel” in Squirrel Hill called the Morrowfield. The story we were told was that Borscht Belt performers would stay there when they were booked at the nearby Squirrel Hill Theatre (before it turned movie house)—Fanny Brice, Al Jolson, and the Marx Brothers had all been guests at the Morrowfield Hotel. By late 2005, a spacious one-bedroom was ours, with all the high ceilings and 1920s closet space I could have dreamed of—three walk-ins for two people, not including the old linen closet out in the common hallway. On days when I missed my former life, I cheered myself up by picturing my favorite Harpo Marx scene, the one from Room Service where he’s chasing a wild turkey around his hotel room with a baseball bat. He misses the turkey but lands a swing squarely into the lamps and vases. Gobble-gobble-SMASH! Gobble-gobble-SMASH!

Along with the endless red-carpeted hallways, the crystal doorknobs, the mirrored lobby, and the gilded mail chutes, one of my favorite of the Morrowfield’s fixtures was our superintendent, who lived, out of all nine wide floors, in the unit right across the hall from us. Victor had come to the States from Ecuador to be a soccer player, but after a bad deal in New York, he’d landed in Pittsburgh. The thing about him was that he still moved with his own energy. No matter how long his day had been, or how hard he’d worked, the world had not wrestled him into a straitjacket. Some people are spared life’s beatdown because of money and support; some people are fighters and resisters; others succumb completely. Victor fought life’s indignities and won a little each day.

Within a couple months of our move, I was working a temp position in the former Hotel Schenley, an 1898 establishment that was created for Pittsburgh’s industrialists to discuss the new civic center they were helping to build. The Hotel Schenley, known as the Bellefield Hotel during its construction, was plunked down on the edge of sloping cow fields as developer Franklin Nicola and his industry titan friends (the likes of Carnegie, Frick, Heinz, Mellon, and Westinghouse) plotted Oakland’s transition from a Victorian suburb to a bustling cultural district with some breathing distance from the thickest factory smoke. Now a student union for the University, the old hotel held offices for the many student services, and I was stationed at one of the desks there.

I was still adjusting to the new-economy meaning of the word “temp,” which meant all the duties and none of the benefits. My supervisor was a regal beauty named Evelyne. She was very mean. Not normal mean like in reaction to things, but unnecessary mean, saying surprising things. She’d often chastise me for not doing things she hadn’t asked me to do. She went to a staff meeting that, as a temp, I wasn’t allowed to attend, and she signed me up for two committees, saying, “It’s time you took some responsibility around here.” Evelyne was very pregnant. I associated her mean streak with her pregnancy, as if she were angry to have a stranger renting a room in her body and needed to take it out on the nearest person, on the new girl.

During that cold winter, I brought peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to work and ate them downstairs, in the beautiful lobby that harkened back to the hotel’s heyday. I marveled at the leftovers of Beaux Arts opulence. I climbed the marble stairs that went to nowhere, just up to the framed photograph of “Pittsburgh’s Billion Dollar District” and back down again. I sat in the plush chairs among the squared columns and wrote in my journal. I read the plaque about Eleonora Duse, world-famous tragedienne of the Italian theater, who died of pneumonia in her fifth floor Schenley suite two weeks after her last performance at the Syria Mosque one rainy night in 1924.

“‘We’ve sat in hotel lobbies all over New York and all over the world, and it’s always nice, I said. The lobbies are always the best looking place in the hotel—you wish you could bring out a cot and sleep in them. Compared to the lobby, your room always looks like a closet.” —Andy Warhol

Not every Pittsburgh traveler slept in such luxury. In Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, playwright August Wilson introduces us to characters in a Hill District boarding house to tell a tale about restlessness, searching, and hopeful journeys. It’s 1911, and African-American men and women are flocking to Pittsburgh and other industrial cities from farms all across the former slave states of the South. Looking for work, looking for family members, looking for a new life, looking for a furnished room they can stay in for a little while until they get their bearings. Seth and Bertha Holly offer rooms for $2 a week, including baths and modest meals (and 25 cents extra if you don’t have your own towel). Their newest boarder, Herald Loomis, has been searching for his wife for years and can’t seem to move on from his past before he locates her: “I been wandering a long time in somebody else’s world,” he says.

Across the river in Homestead, typical boarding houses in the same era cost $3 a month for immigrant workers making $1.65 a day in the steel mills. This rate bought a slender sleeping spot in an overcrowded tenement home, plus the most basic meal, mostly meat stew and bread. In one such house, a Bulgarian family of four, plus twenty Slovakian boarders, shared a space of just two rooms. The bars of Homestead’s Eighth Avenue were full of immigrant workers trying to drown their exhaustion and homesickness. In another part of town, railroad workers slept in dormitories made out of box cars.

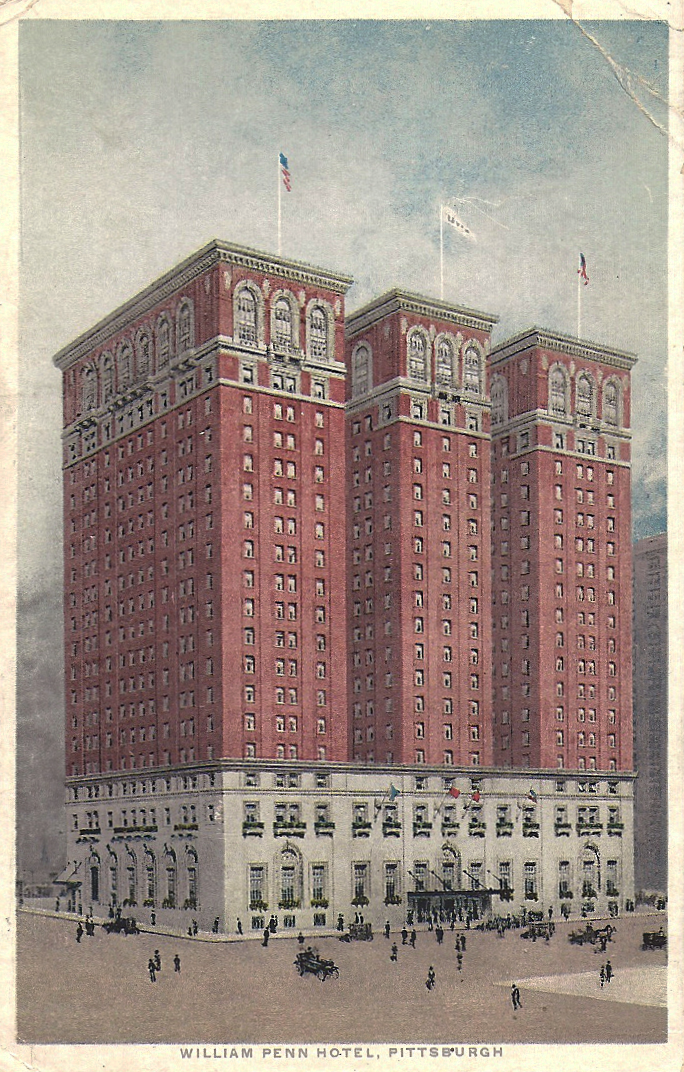

It was something like homesickness that led us to serve turkey dinner to the needy one Christmas Day early in our new Pittsburgh life. We took a 61C down to the Omni William Penn and were shown through a service entrance to the Three Rivers Room on the lower level. The standard, low-ceilinged banquet facilities were dreary compared to the opulent lobby and enormous Christmas tree we’d caught a glimpse of above. Down-on-their-luck families and single men wore their Sunday best as we refilled their water and bread baskets. We cleared away their dinner plates when they were ready for dessert.

The William Penn Hotel opened in March of 1916 to much fanfare, earning the nickname of Pittsburgh’s “Grand Dame.” To draw visitors to downtown Pittsburgh, early advertisements stressed that “all air for restaurants and public spaces [were] to be thoroughly washed.” The William Penn lured presidents and entertainers to its deluxe suites and attracted Pittsburgh’s high society to the Georgian and Italian dining rooms flanking a main lobby lined in French walnut. Company meetings and society weddings were held on the 17th floor. Here Charles Lindbergh was feted in the Grand Ballroom; John O’Hara fell for Bob Hope’s future wife as she sang in the art deco Urban Room; Lawrence Welk debuted his bubble machine when his orchestra played their Saturday night radio show to a Pittsburgh audience. Even today, the E-shaped floor plan and soundless, thick carpets lend an air of mystery and luxury to the sleeping corridors of the hotel. On lower floors, the stenographer’s services are no longer available, but you can still buy a newspaper or get your shoes shined.

In the earliest days, a Pittsburgh hotel was a tavern or an inn run by a keeper or a couple out of their home, back when travel was slow and difficult and meant battling rivers full of insects, nascent roads full of pitfalls, and forests full of thieves. By the time he got to Pittsburgh, all a traveler wanted was a stable for his horse, a hearty meal, flowing alcohol, and a bed to pass out in, even if it already contained four other men asleep with their boots on. Pittsburgh’s innkeepers were a lively bunch who competed with each other via colorful wooden signs and overseas newspaper ads.

The Monongahela House opened downtown in 1840, convenient for steamboats arriving along the Mon Wharf. The 210-room guest house was Pittsburgh’s first version of a new American concept—a full-service luxury hotel for VIP travelers. But with an abolitionist sympathizer as its proprietor and 300 free Black employees on staff, the hotel gave wealthy Southern guests an unwelcome surprise: If they were traveling with slaves, the waiters, cooks, and chambermaids of the Monongahela House tried to “kidnap” the captives and help them escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad.

“It is unwise to leave the choice of a hotel to a hack or a taxi-cab driver.” —Pittsburgh: How to See It, 1916

I ran into Victor more often than other residents of the Morrowfield. He’d keep me guessing over his odd stories, tales about watching a wild turkey wrestle a hawk in the middle of Murray Avenue, or about the Russian fight club that went on at night in between the Morrowfield and the Alderson apartments behind us. One day he showed me the empty ballroom of the old hotel: In the mid-century, a bright and glamorous room for weddings, bar mitzvahs, company banquets, and society dances; these days, just a darkened storage area.

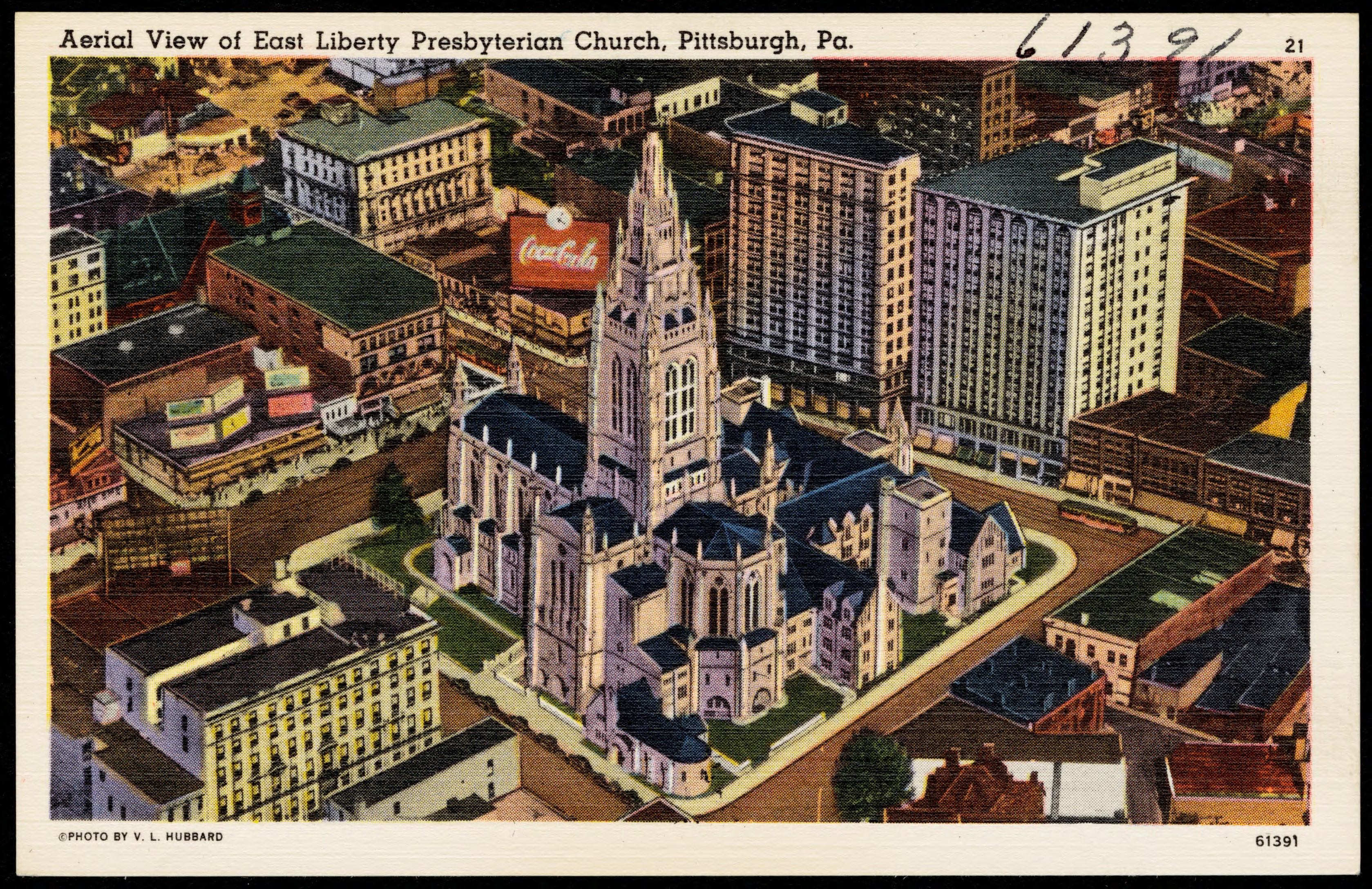

When the Ace Hotel arrived in East Liberty in late 2015, it christened Pittsburgh as an It City among the boutique hotel’s short roster of It Cities—not a small honor for a city that got used to being an American punchline. But the Ace also returned to us the old idea of a hotel: a chic place to see and be seen; a place for cutting-edge professionals to sleep, drink, and network; an establishment that experiments with trendsetting decor and food; a venue that hosts fashionable events aimed at discerning locals. The Rooftop Biergarten at the Hotel Monaco and the glass-walled Andy’s at the Fairmont are other examples of this return to courting local aesthetes, but the Ace in the East End may be the best situated for it—and its emphasis of “hip” over “luxe” can attract a younger crowd. Perhaps fittingly, the Ace opened with an exhibit of the photography of Teenie Harris. Harris is known for his prolific snapshots of African-American day-to-day in Pittsburgh, but especially for capturing the vibrant nightlife of the lost hotels and clubs of the Hill District, where through the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s all of Pittsburgh came to drink, dine, gamble, and swing to the city’s unparalleled jazz scene. In those days, Gus Greenlee could buy up a corner flophouse and turn it into a legend.

“We all three went to Man Ray’s hotel. It was one of the little, tiny hotels in the rue Delambre, and Man Ray had one of the small rooms, but I have never seen any space, not even a ship’s cabin, with so many things in it and the things so admirably disposed.” —Gertrude Stein in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, 1933.

Victor left the Morrowfield in a hurry one night and never came back. We left for work one morning and saw his door flung wide and a room full of overflowing ashtrays, strewn beer cans, and an empty safe. We, too, left the Morrowfield soon after and bought a house on the other side of town. Closer to the Allegheny, closer to smaller hotels—to Brewer’s, a residential hotel above a gay dive bar; to the Eden House Short Stay, a row house hotel where artists involved in Pittsburgh collaborations or actors in local film shoots park themselves for weeks-long projects; to the Round Corner Hotel, which was once the “town stopping place” of choice for many farmers and their horses from as early as the 1860s.

“The only room in the hotel was not comfortable. Etta bade her sister put up with it as it was only for one night. Etta, answered Doctor Claribel, one night is as important as any other night in my life and I must be comfortable.” —Gertrude Stein in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, 1933.

After my years on the seventh floor of the Morrowfield and an adulthood of revolving apartment houses, it’s unsettling to live on the first floor again. After a lifetime of relocations, it’s baffling to own a home and a backyard. A part of me is grateful for the sense of stability. Another part of me is compelled to seek the two-star guest houses of other cities and to haunt the lobbies of Pittsburgh’s grand hotels, old and new.