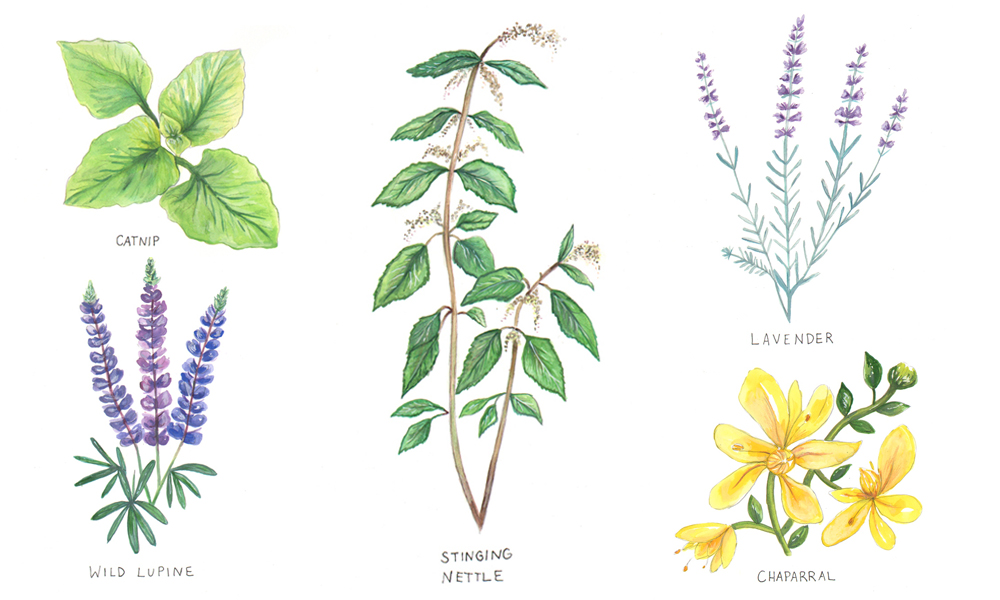

Anise hyssop can be used to treat heartbreak. Steep the pulverized herb in hot water to make a tea that will resolve the imbalance between head and heart. Cherry bark suppresses coughs. Dandelion returns a lost appetite, treats swelling and ailments of the liver. Stinging nettle contains histamine, which can be used to treat asthma or reduce joint inflammation. Chaparral can stop the development of tooth decay.

Michelle Soto, who started Cutting Root Apothecary last year, had a bin of chaparral on the top shelf of her stock. She took it down so I could breathe it in deep. It’s sharp and pungent, a bit like sage. She gathered it from the Sonoran Desert where it grows so abundantly that the smell pops out every time it rains.

Soto told me that chaparral is a plant of endurance. It survives by restricting the access of other plants to water. It shares a name with the ecosystem found throughout Southern California, which includes sage and ceanothus, chamise and manzanita. Under the right conditions—when the heat is high and humidity low—these plants can burst into flame. The other name for chaparral is creosote, after the chemicals formed from distilled tar, commonly used to treat railroad ties to prevent them from rotting. Chaparral “kills shit,” Soto says. It stops not only decaying teeth, but maybe even the development of tumors.

The herbalist gathers the chaparral twice a year, in April and November, when she and a small group of other herbalists and medical workers go to Arizona to organize a free health clinic for the elders at Black Mesa. Black Mesa is the site of the Peabody coal mine, constructed on land sacred to both the Hopi and the Navajo, or Dinai, people. As a consequence, it is also the site of the largest 20th century government-sponsored relocation of a people in the United States. Eight years ago, the reservation asked for alternative health medicine for the elderly members of their community. The clinic provides elders with treatments to last them for the months in between visits.

“We are caring for the people who are caretakers of the land,” Soto said as she snapped shut the lid on the chaparral and returned it to its designated place, the place from where everything had connected to everything else.

![]()

Soto grows as many of the herbs for Cutting Root Apothecary as she can at her farm in Butler County, about an hour north from Pittsburgh. I drove up with two friends one morning at the end of May, turning left at the sign for Mazzanti’s Beans and Cream onto a private drive hemmed in by towering purple clusters of wild lupine. Something about the property—the lupine, the ram’s skull by Soto’s cabin door, the heavy-headed peonies in the garden—lifted me in a way I had not felt since a premature Pittsburgh summer had arrived.

The property is owned by a man named John, who lets Soto grow her herbs and flowers there so the land can be used for a good purpose. She and her business partner, Meg Graham, raised the fence to their plot on Easter Sunday a year ago with the help of some neighbors. They planted each row of herbs as soon as it was prepped: yarrow and nettle, valerian and elecampane.

When I arrived there were rows of seed trays by the garden gate, slender catnip seedlings putting forth silvery-green leaves. Soto showed me where to plant them, the rows that needed cleared of weeds, the volunteer nettle and lavender and dandelion that I should not pull out. I thought about a poem Emily Dickinson wrote on a scrap of gift-wrap, describing how a dandelion slips away a bit at a time, scattering itself into two thousand seeds. Emily Dickinson associated certain flowers with certain people and wanted desperately to believe in paradise. She wrote the cycle of the garden, its births and decays and rebirths, in pursuit of it, and used poetry to alleviate the pain she felt upon witnessing spectacular beauty.

Dandelions are hated for their long, grasping roots, their clenched grip on the earth. More often than not they have to be cut, and I wondered why more gardeners didn’t honor this resiliency. Despite all the death a garden contains, dandelions are always coming back. I finished planting the row of catnip, then carried water to and from the spigot in a metal can, sloshing it all over my clothes.

Dandelions are hated for their long, grasping roots, their clenched grip on the earth. More often than not they have to be cut, and I wondered why more gardeners didn’t honor this resiliency. Despite all the death a garden contains, dandelions are always coming back. I finished planting the row of catnip, then carried water to and from the spigot in a metal can, sloshing it all over my clothes.

At noon we broke to eat lunch in Soto’s cabin, piling anchovies, mayonnaise, cheese, and avocado on homemade bread. She took us for a walk in the woods that edged the property. She showed us the wild plants that would flower and bear fruit, and I forgot their names almost as soon as she spoke them. Every now and then we would come upon a patch of white fleece blanketing the ground, a lost sheep from last year’s flock. I unraveled a single vertebra from the wool and carried it by its two wingtips.

As we left the farm, my friends stopped to gather some of the lupine to take back to Pittsburgh. The flowers scattered all over my back seat. Weeks later, after the lupine died, I learned that each lupine flower contains six edible golden seeds, known to aid in digestion, boost immunity, and strengthen the heart; that there is a small, endangered blue butterfly whose life depends entirely on the presence of wild lupine; that this endangered blue butterfly was first classified by Vladimir Nabokov, who wrote about them fluttering “…and revealing the celestial hue of their upper surface…like blue snowflakes before settling again”; that this passage is recognized as the loveliest description of butterflies in literature. When I saw the lupine, I didn’t consider these obscurities. I only knew they were beautiful.

In the documentary Juliette of the Herbs, herbalist Juliette de Baïracli Levy describes treating a patient who had been in a horrific car accident and developed gangrene in her injured leg. She says she wrapped the woman’s wound in huge nasturtium and marigold leaves, which blackened as they extracted the poison, as though mirroring the injury. When the patient’s wound healed, the leaves peeled away painlessly. “If every hospital had its garden growing these plants instead of their shelves and shelves of chemical medicine, there would be so much less pain in the world, and successful healing,” Baïracli Levy says.

Herbalism is the systematic study of relationships, and for this very reason it is regarded with skepticism. In its earliest form, herbalism relied upon the notion of sympathetic magic, or the idea that a plant’s connotations revealed its properties. For example, a mushroom gathered from a rotting tree could put life back into a corpse. Although it was flawed logic, the methodology relied upon the understanding that people are a part of nature, and that the way plants grow mirrors what they do in the body, because both the body and the plant are in a symbiotic relationship with the world at large.

When the pharmaceutical industry was first developing in the early 19th century, scientists extracted and modified active ingredients from plants. They began to make their own chemical versions of the plant compounds, resulting in drugs that worked faster and were perceived as easy fixes for physical ailments. Herbalism is more complicated than a prescription because it is about observation and finding and maintaining a balance. It takes time and patience, requirements that aren’t necessarily suitable for every patient. Even still, nearly a quarter of modern medicine still uses botanical ingredients as the basis for its formulas.

![]()

Soto’s apothecary, which she runs out of her apartment in Wilkinsburg, was full of light. She had fifteen varieties of lavender growing in seed trays in the window, and shelves of glass bottles, dried and sorted flowers and herbs. When a customer comes for a consultation she meets with them for about two hours, talking about everything that could possibly ail them. Most people aren’t used to talking about their health for that long, but each ailment contains layers, Soto told me, roots, which need to be understood to determine a course of treatment. Herbalism treats the source of the issue, not only its symptoms. While there are many herbalism schools, the ones that are rooted in folklore link the manifestation of symptoms to elemental properties: metal, fire, water, wood. Imbalances in different kinds of people lead to the presentation of different kinds of ailments.

I asked Soto how open her clients are to talking in this nontraditional language, and she admitted that she doesn’t always offer everything up the first time they meet. Her consultation involves evaluating what people are accustomed to, which includes their history with doctors and prescriptions. If a client is used to taking pills, she recommends capsulated herbs instead of tinctures or teas. Even though the expense of healthcare means that more people are turning to natural medicine than they were in prior years, most people have only a superficial understanding of the properties of plants, and only a few become absorbed enough to expand their knowledge further.

Soto used to have a somewhat superficial understanding of herbalism herself. Gathering plants was a pastime for her as she traipsed through the woods with a paperback field guide and Alvarez, her dog. She liked herbalism’s autonomy, the fact that she could teach herself how to fix her body the way someone else might teach themselves how to fix a bike. In 2011, she started enrolling in courses, and since then she has studied in Vermont, Colorado, Alabama, and elsewhere under chemists, botanists, and indigenous practitioners. She visits a new place and investigates a different practice every year. She told me that one of her teachers was a sixth-generation herbalist who had learned primarily from her Cherokee grandmother, and who had not found anyone within her own family to teach. The knowledge is going to go away, Soto was saying, unless more people learn.

She offered to sell me one ounce of the anise hyssop, the herb to treat heartbreak, but I asked for two. She spooned the pulverized flowers and leaves into a paper sack for me and included two muslin bags for steeping. Later that night I boiled water to make the tea. As I waited for the kettle to sing, I did some light Googling about the herb, which only turned up its uses to treat coughs, fevers, wounds, and diarrhea. Well, I thought, I’ve had some of those too.

She offered to sell me one ounce of the anise hyssop, the herb to treat heartbreak, but I asked for two. She spooned the pulverized flowers and leaves into a paper sack for me and included two muslin bags for steeping. Later that night I boiled water to make the tea. As I waited for the kettle to sing, I did some light Googling about the herb, which only turned up its uses to treat coughs, fevers, wounds, and diarrhea. Well, I thought, I’ve had some of those too.

When it was ready, I drank the tea. It tasted slightly sweet, a bit like chamomile. I paged through the herbalism books I borrowed from Soto’s library but couldn’t find a mention of the herb. From my own bookshelf, I pulled down Prescription for Nutritional Healing, probably the most well-known book about natural remedies. Anise hyssop was not listed in its index, either. I drank the tea and kept turning through the book, its indexes of ailments. As I did, I thought about a woman I met the summer before, a former veterinarian assistant who came out to the farm where I was working once a week to weed in exchange for produce. One night a chicken had become caught in the wire of its coop. The others had started to attack it and by the time we found it in the morning, half its breastbone was exposed. Its crop, where chickens store their food, was sliced, and I thought killing it would be the kindest thing. But the woman stitched up the bird with a sewing needle and thread and treated the wound with a poultice made from goldenseal – a practically magical herb, she told me, that killed any infection. The chicken survived, protected in the greenhouse for the rest of the summer among the lettuce and microgreens.

If a chicken could be brought back, why couldn’t a person, I thought. When I asked the woman how she had learned about the goldenseal, she recommended Prescription for Nutritional Healing to me. I ordered it immediately, and a few weeks after I returned from the farm I found it waiting on my porch, heavy as an ancient tome. I looked up black cohosh, butcher’s-broom, cayenne, chickweed, horseradish, ginseng, rhodiola. I was trying to save somebody I loved, believing that every illness could be cured, not yet knowing that reconciliation with loss can be a kind of healing, too.

Since I could not find the anise hyssop listed, I closed the book and replaced it on my shelf. When Soto gave me the tea, she told me that time was the most important component of any herbal treatment. Part of the healing occurs in the time it takes to heat the water. The time to soak the tea. The time to sit with the tea until it is cool enough to sip slowly. So I sipped my tea slowly, so slowly, that it took a few long minutes for me to notice the slight lessening of my wound-up ache.