Pardon, je ne parle pas français. I fumbled through my new mantra, buttressed by two years of high school French. I’d joined my wife during a business trip this past June, but our expectation for a tranquil tour of France was dashed, thanks to the convergence of the worst flooding of the Seine River in sixty years, a labor strike that complicated travel, and swarms of Euro 2016 football hooligans. So we fled Paris for the tranquil Loire Valley city of Amboise, in what’s called the “Garden of France,” driving past charming vineyards and farms.

Our initial drive was estimated at two-and-a-half highway hours, but after a self-induced detour onto single-lane roads through castle towns, the trip grew to more than five hours. Halfway through this trek, a familiar feeling arose—the creeping realization that though you haven’t covered as much ground as you thought, there is nothing left to do but move forward. With my hands on the wheel, flipping through unintelligible talk radio stations, a connection to my recent artistic practice sparked: As my creative goals have progressed, it’s necessitated a greater amount of work, I theorized. Before, I was blissfully ignorant, but now—realizing I’d run through a number of great ideas, and faced with a rising personal standard which in turn increases the amount of investment of time—now, things are different. Envying how easy it used to be, I knew there’s no going back.

In the spring of 2013, I set up a camera in the Mine Factory studio of encaustic painter Stephanie Armbruster. I filmed Armbruster carefully pulling a large canvas off the wall, laying it flat on a table, and applying a layer of wax. She smoothed the rough edges with a razor, adding more layers of powder pigment, and then more wax. An hour later, I had solid footage for Ongoing Box, a documentary film about artistic process. Two hours after I returned home, I completed the edit for a five-minute section of the film. Today, I’m happy with it. It’s one of my favorite scenes in the film. Roughly three hours of work equated to five minutes of movie magic. Not a bad ratio in the filmmaking world.

For the past two yeas, I have been documenting different aspects of Pittsburgh-area food culture for my Food Systems documentary series. To deal with nuance in conversation about restaurants, the environment, labor, gentrification, and hunger, I’ve needed to consider more storytelling options, film more interviews, weave together discussions and arguments, and find B-roll to edit around the many ums and uhs and likes. With each film, I’m getting closer and closer to a more representative story of Pittsburgh food. But now I’m lucky if five minutes of footage equates to 15 hours of filming, editing, color correcting, sound creation, and narrative revision. I don’t have an interest in the admittedly easier, non-narrative documentation of a process. I’ve already done that. I want to tell complex narratives. There’s no going back, and there is so much more to do.

Armbruster seemed to relate. “I’ve always been very prolific,” she told me, “but in the past couple years, I’ve found that I need to take breaks between series, shows, and major works. It’s become important to fully realize a series for what it should be, and then step away long enough to contemplate what comes next.”

Since our video shoot three years ago, Armbruster has had a solid streak of solo and group shows, each documenting developments in her work. The 2013 Pittsburgh Center for the Arts exhibit Hungry Ghosts was a beautiful example of how encaustic painting can transform a canvas. Her recent work has integrated her background in graphic design and street art with abstract landscapes, and though relatively silent in 2016, she has participated in a number of group shows this summer, including John Riegert at SPACE Gallery, the Global Day of Discovery pop-up, and the Future Tenant group show New Order: Collage Now.

“I’ve started granting myself time for creative exploration and a fresh perspective when I feel it’s needed,” Armbruster told me, “even if that means going six months without producing finished works. It’s hard to get over the anxiety of not-making at first, but the work that follows is ten times more inspired than if I hadn’t taken that break. It keeps my studio practice fresh and fulfilling and removes any sense of obligation.”

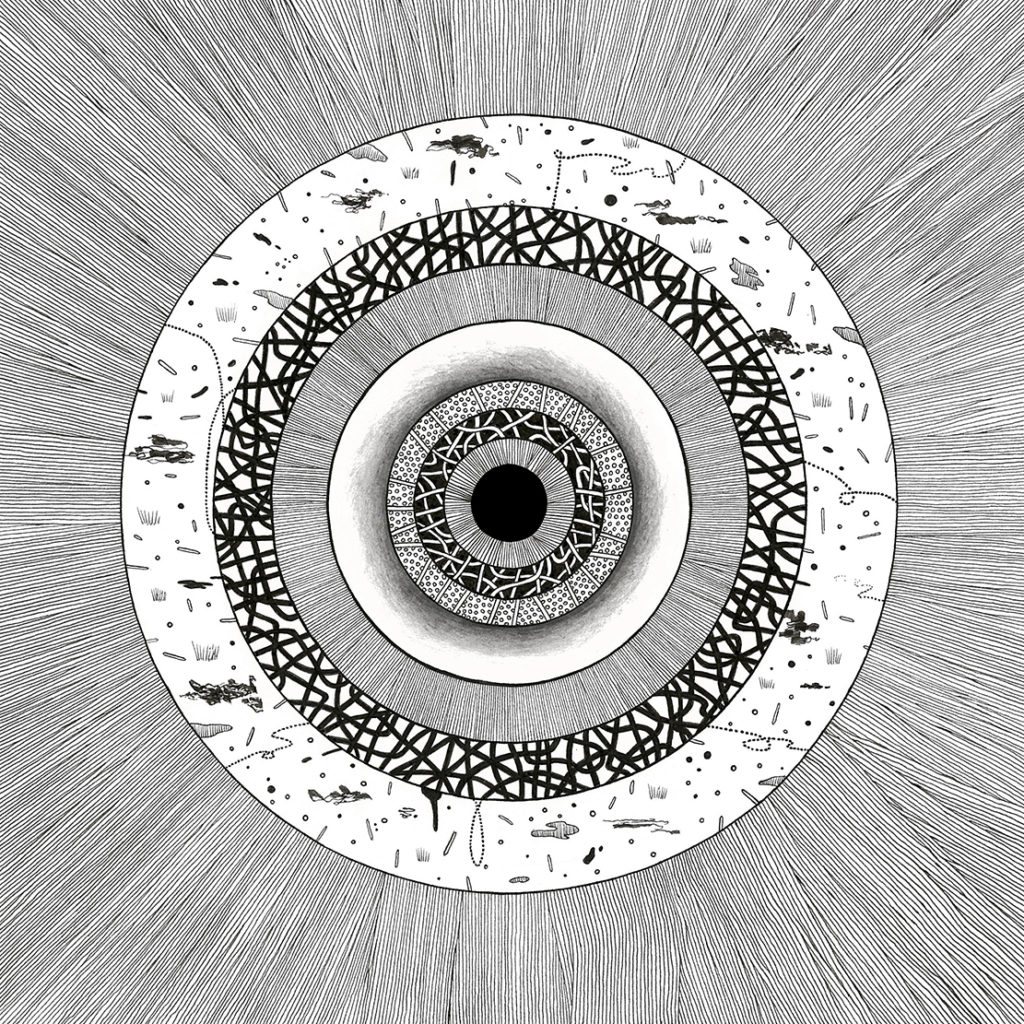

Packed with painstaking line-and-dot intricacies, Johnstown native and New York-based artist and musician Brandon Locher‘s Mazes to the Motherlode series requires drawing sprees that can last upwards of 40 hours a week. And as he adds more and more to this long-running series, “Composition and ideas for new pieces sometimes take as much time as physically drawing and executing them,” he acknowledged. “With each new piece I’m always constantly trying to become more introspective and connected to my own individual journey. My method of working is generally always very premeditated and doesn’t allow much room for chance.”

Locher has been releasing creative work on his label My Idea of Fun since 2007, from albums of sonic experiments like his phonebook-random call recordings of Conversations, musical projects with his groups The Meets and Stage Hands, and handmade photography books and physical art pieces.

“Because I’m not interested in repeating myself compositionally and want this journey to stay fresh and exploratory, making new works takes much more time and direct attention than in the past,” Locher said. “As my work expands, my ambitions become larger, and as a result, I find myself working slightly outside of my own means. Making these works will never get easier and will only continue to present more additional challenges in the months and years ahead.”

Documentary filmmaker Chris Ivey has logged over ten years on his East of Liberty documentary series. Ivey was hired to film the 2005 demolition of the East Mall high-rise and found that longtime residents did not share in what was, to some, a celebration. Since then, Ivey has transformed from commissioned videographer to documentarian on a mission. With two additional films on the way, East of Liberty: Youth Rising and East of Liberty: Communities Without, the five-film series details the redevelopment of East Liberty neighborhood, the impact of the interests of public and private institutions, and the associated issues of racial and class inequity.

“When I make a documentary, whether for a client or myself, I have come to realize that you cannot rush it, period,” Ivey said. “You can have all the elements of beauty—dolly moves, damn drone shots, etc.—but if it doesn’t have a soul, what do you have?”

As Ivey framed it, sometimes this moment of “no going back” relates to balancing your own expectations of what the project should be with the expectations of an outside party, often in the form of a funder. You become aware of the need to analyze the work you did, refine it, and make it as potent as it can be. This can take time—time to think, time to try different options, and, in the case of filmmaking, time to pick the best solution to the endless possible editing paths.

“I remember several years ago when I got funding support from a foundation for a project and I had to keep pushing back their deadline for completion,” Ivey told me. “The film did not feel right. It was incomplete, and I knew I had a lot of work ahead to get it right. At the time, I was trying to work in the Pittsburgh Public Schools. The individual school administrations were ready but the head PPS administration in Oakland was non-responsive. After what turned out to be a couple of years of silence, I felt under pressure to show something to the funders who were constantly asking when the film was going to be completed. And then it hit me: Forget about the damn deadlines. Why was I killing myself to get this done? I had to remind myself that I was not making a project for a client but making a project that will be a unique tool for teens. A tool that will hopefully inspire and motivate teens to think more critically about their environments becoming more gentrified. I had to remind myself who the work really was for and that kids were all that mattered.”

Much of documentary filmmaking is a tool for education and activism, and with that comes responsibility. Finding interviewees and working to uncover a fuller story can seem like an endless task. You can always go deeper, but you need to find a balance between telling the story and taking care of yourself in order to be able to continue the work. “I think it’s easy for independent filmmakers to run ourselves into the ground,” Ivey said. “It’s always important to take a step back, look it all over and feel accomplished to a degree. There is still a lot to be done, but you’re doing the work… Feel good about it when you can.”

“Begin not from preconceived idea of what to say about image,” Beat icon Jack Kerouac once advised, “but from jewel center of interest in subject of image at moment of writing, and write outwards swimming in sea of language to peripheral release and exhaustion… Never afterthink to ‘improve’ or defray impressions.”

But “there’s debate about how true Kerouac was to the ‘never afterthink’ rule in his own writing,” David Leicht told me. “In other words, he might have edited himself more vigorously than legend would have us believe.” Leicht, who performs and composes for the band Pairdown, crafts songs that may not include a wealth of words, but the lines that do emerge from the intense, harmonically-rich music are elegant, often humorous, and completely captivating.

“More relevant to me, though” Leicht continued, “is the advice to begin from ‘jewel center of interest,’ which I take to mean ‘have a clear and evocative idea from the outset.’ My standards over the years have not changed as much as the rate at which I can identify song ideas has slowed.”

“My early lyrics for Pairdown, a ten-year-and-counting collaboration with Raymond Morin that now includes Sue Powers and Jeff Berman, centered on ideas that were natural or obvious to me. For example, I wrote ‘Nonlinear Lions’ in 2005 after visiting friends in Southern California regularly for years. The title was coined by native SoCal theorist Mike Davis in his book Ecology of Fear. He discusses the seemingly never-ending outward expansion of Los Angeles and the adverse effects a wealthy Californian might endure after building a trophy home at wilderness’ edge (fires, slides, lion attacks). After driving and hiking around there a good bit, it was easy for me to see what Davis was talking about, and the song idea came naturally. Fleshing out lyrics around it was probably slow, because I like to tinker with words, but also steady and joyful. When I listen back to the recording, I may wonder about the performance but am happy to hear the central idea coming across clearly.”

But after more than a decade, Leicht said, “I’ve written lyrics for about twenty songs, and the obvious ideas have been used up. I don’t want to repeat myself, so I either have to think harder (which doesn’t work) or just wait for new ideas to dawn on me. Unsurprisingly, I write fewer songs these days.”

Of course, fewer songs still means that songs have indeed been written. For his track “The Salmon” on Pairdown’s forthcoming album, Leicht described identifying and building around a “jewel center.” Embracing the limits of creative output can provide a kind of built-in quality control. “Having a clear idea for guidance brought joy and ease to writing the lyrics,” Leicht said. “And while I concede that [“The Salmon”] is an oddball song idea, I don’t expect to be cringing or second-guessing when I hear it ten years from now.”

![]()

One luxury of vacation is time, and last month I used it to review, analyze, and plot. Part of the reason that I flip from film to music to art to dance is out of a need to take the time to digest what I created in one medium before returning to it, I decided back in Pittsburgh, sitting in my eternally cluttered office. The artists I spoke to described a drive to originate and not repeat oneself while managing a lower volume of output, or mandating time for reflection before starting new bodies of work, or acceding to the external pressures of the artistic markets. But in the end, it all comes down to the work. Acknowledging changes in your creative practice allows you to adapt to new environments or interests. And whether or not it takes a longer amount of time, or whether it is harder to make, the work must continue. There is no other option except to create.