“At the Seder it represents the bitterness of slavery,” Rabbi Sharyn Henry of Rodef Shalom explains. “If you eat something bitter, then it could make your eyes water. So there’s this idea that you would have the empathic response to someone being a slave or if you were a slave yourself—you experience that bitterness, and you would have tears.”

The brassica root Armoracia rusticana is an ideal tearjerker. Its pungent smell hits you first. It opens your nasal passages but takes your breath, and, like a punch, it can feel as if it’s physically knocking you back a bit. Botanically related to broccoli, cabbage, and mustard, the horseradish root contains self-defensive enzymes and chemicals that are activated by saliva and air to create the intense, bitter-heat gustatory kick that is often associated with home-cooked, old-world cuisine.

On the side of the Heinz History Center building in the Strip District, a giant digital bottle of ketchup pours, refills, and pours again: The name “Heinz” is practically synonymous with the sweet, red condiment. Today, after a merger with Kraft, Heinz represents a super-company with a global portfolio of thousands of products. But in 1869, it was all about the horseradish.

Horseradish was the bedrock of Heinz Noble & Co, the Sharpsburg-based company co-founded by Henry J. Heinz in 1869. The son of German immigrants, the teenaged Heinz recognized the need—and opportunity—to manufacture quality horseradish during a time when food safety was a major concern. Fresh, grated horseradish sold in clear bottles, unlike competitors who used dark bottles to hide the questionable quality of their product (which could be cut with turnips, wood fibers, or other unwanted fillers), represented honesty and integrity—a keen marketing pivot.

Horseradish may still exist under the radar today, having largely avoided the spotlight of earnest hipster acclaim, though Collinsville, Illinois—located in the Mississippi River floodplain known as the “American Bottoms,” where the vast majority of American horseradish is grown, does host an annual festival dedicated to the root. There may never be a group of young farmers tilling horseradish fields, soaking their beards in horseradish oil whilst sipping horseradish tea. All the better. Instead, horseradish’s qualities are appreciated more quietly, and Pittsburgh chefs like James Street Gastropub and Speakeasy’s Jon Dulude, are exploring the ways this powerful condiment can complement a meal:

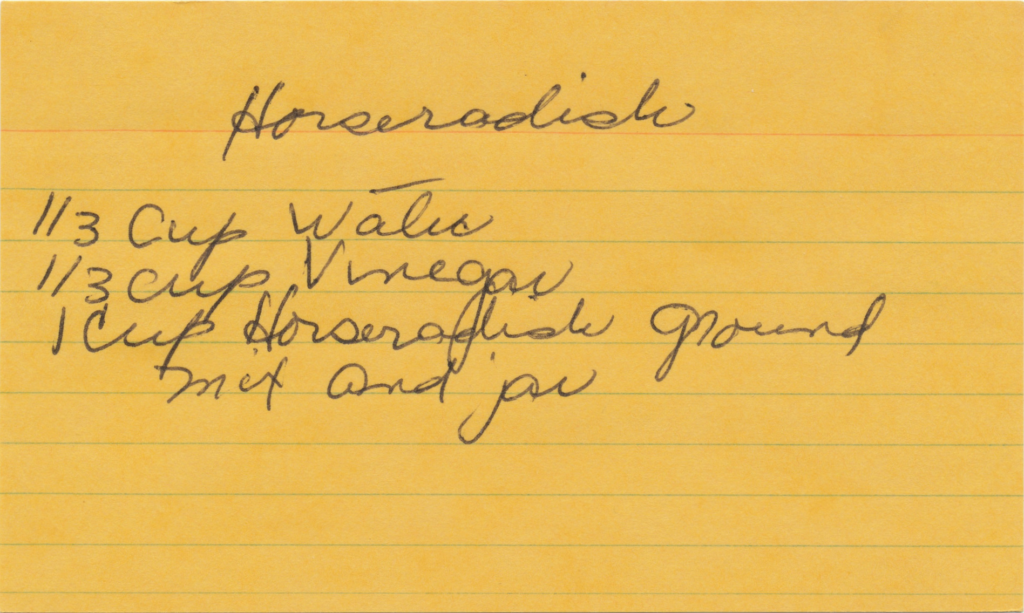

At Legume in North Oakland, Trevett Hooper uses prepared horseradish in sour cream to pair with wurst. Legume has also recently offered horseradish butter, with prepared horseradish and anchovies mixed together and served with warm mushrooms on rye toast. In the spring, Hooper sources fresh horseradish from an Amish farmer based in Somerset so that Legume can create the condiment by hand—which becomes something of an event.

“When you prepare it at home yourself it’s pretty intense,” says Hooper. “I mean, it’s noxious. The whole kitchen just gets this horseradish gas and people on the other side of the kitchen will start coughing depending on the air flow. It’s really crazy.”

![Horseradish leaves. [Edsel Little/CC BY-SA 2.0]](http://theglassblock.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/7322462730_4dfaeef044_k-225x300.jpg)

“I grew up with a lot of horseradish,” says Skowronski. “Poles have a lot of horseradish—and they have good horseradish. I find that horseradish in the United States has more of a bitter aftertaste than in other places. In Poland you have a lot more wild horseradish, so it’s brighter and bigger. We actually planted some [in Pittsburgh] and we’re trying to have them take hold. We’re really intent on using horseradish because it has such big, bold flavor. ”

Skowronski, whose family is from Warsaw, recounts summer visits in Poland pulling fresh horseradish from the family garden and, with the oversight of his grandfather, grating the horseradish with apples and lemons and serving it over cream.

“When I drive on the road and see a horseradish—especially in Poland, they have very recognizable leaves, big, like burdock, and you see them on a lawn or garden or somewhere—I always think, man, I should dig that thing out and just have it because who knows when I’m going to need it. It’s got such a big, bright flavor [and] I think a lot of people aren’t sure what to do with it.”

Apteka has plans to use horseradish in cordials and liqueurs, which Skowronski explains comes from traditions in Poland and Ukraine. The process involves soaking horseradish in grain alcohol or vodka while adding spices like black pepper, dill, coriander, or allspice. Though it sounds great as a Bloody Mary mix, Skowronski explains that it’s traditional to drink it straight: a true taste of the Old World.

Oftentimes with a food like horseradish, there’s a deep sense of home and family history. In Pittsburgh, that history helped build a nationally recognized brand. Today, Pittsburgh chefs are tying in traditions that go back centuries with contemporary twists. Buckle up, breathe deep, and embrace the punch.