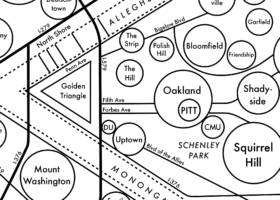

If every city is a text then Pittsburgh is the one I’ve read most intimately. It’s the one I keep revisiting, this book of lives overlapping as they unfold, some of them synchronously, some wandering off the page, some picking up where others have ended, going on, changing into something else, the way women like Eliza and Carrie became the names ascribed to industrial furnaces and dynasties like Carnegie and Frick became museums and trolley tracks became the divide felt underfoot, a split through the street. To move through the city—with its helicopters and its hospital roofs, its bus routes and bridges, the old river barge laid up against the shore—is to move through its memories, some as peripheral as a colonial fort clinging to the frontier’s edge. Even so, I trace the old outlines. I insist upon their existence.

The Rialto Street staircase is one place of importance. Now most of the trees are bare from winter, but a lacy carpet of green is spreading over the hillside, white blossoms on probing stalks. A bush erupts in flowers the color of cautious hope. Old house foundations litter the slope, still in the shape of the lives they were intended to hold. Corroded pipes, once the channels for gas and water, rise out of the earth like periscopes.

Two years ago, I first learned the stairs by following behind Joe. I remember how he bounded up, balancing his fixed gear bike on his shoulder with ease. The incline stretched so high above me I could not see where the stairs ended, but I hefted up my blue ten-speed and climbed after him.

When we first met I was always racing behind him. Earlier that afternoon he had met me at my apartment in Polish Hill and we had flown on our bikes down Herron Avenue to Liberty. Across the 31st Street Bridge, the wind caught and flung away our words to one another. Joe’s long legs outpaced me no matter how hard I pedaled, but I kept pushing on because that summer I had something to prove about strength and desire.

We were taking the stairs to see the house in Troy Hill where he would move later that summer. I would climb them many times throughout that season. Each time I carried my bike up the staircase, the sweat pooled at the base of my spine and heat climbed my neck to flush my face. Rialto is not the steepest street in Pittsburgh—it doesn’t even place second—but the stairs left an ache in my legs, and by the time I reached the top I had just enough left in me to pedal the last few blocks to Sally’s house.

We called it Sally’s house after the woman who had owned it for decades. Even though she had sold the property, it still felt like hers because she had left it full of her possessions. By the time I arrived, Joe and his housemate had already cleaned out the frozen food and stacked newspapers. They had picked through the fragile trinkets and left them spread out on the heavy dining room table: porcelain horses and seashells and children, crucifixes and ceramic eggs and crystal candy dishes. They had opened up the windows to air out the rooms, pulled the clothes out of the closets and wardrobes, and piled them in heaps in the living room.

My first day at the house, I sifted through the piles of baby rompers and silk slips, polyester blouses and sensible skirts, a teenager’s neon jacket with the Nike swoosh embroidered over the heart. Sally’s husband, who had been a minister before his sudden death, had worn button-downs and heavy wool coats. Sally had pressed his slacks, encased them in plastic sheets, and hung them on wire hangers in ordered rows in the basement’s cedar-lined closet.

At first, the house’s emptying was more of an excavation. We bagged up Sally’s belongings in thick black garbage bags and set them on the curb for the garbage trucks to haul away. The house’s foundation leaked, and we discovered that water had seeped into the cedar closet in the basement. Some of the clothes were spotted with grey mildew. Friends came by and picked through what was salvageable, and now and then I would see somebody wearing a knee-length skirt or sensible cardigan and ask: Is that one of Sally’s? We went through the trinkets too, and her costume jewelry, gold-plated bracelets, angel brooches, and hummingbird earrings. She was still alive, I would remind myself now and again, even though it felt like we were giving away her estate. I wondered whether she approved of us in what had been her space.

One day Joe and I found the sheets of paper on which she had written the story of her life. It took up the front and back of four sheets of paper, written in spidery script. We lay on the floor and read it aloud to one another: where she had been born and what she had hoped for, how she had loved. It accounted for years and lasted only a few minutes, and after it was over Joe folded up the paper and put it in a safe place, and I never saw it again.

Later on, the cleaning of the house became an ordering. When we opened the kitchen’s wood-paneled cabinets they breathed out the scent that had saturated the clothes, the smell of pent-up time. Sally’s husband had kept pamphlets on subjects that included Christianity, puberty, abstinence, and the occult. Joe propped them on windowsills and pantry shelves with irony. We gave the house a different hue, painting the upstairs bedroom clean white, one wall a shade of periwinkle. The old living room carpet, thick with dust, was ripped up. The first night the house was completely emptied I slept on the old couch and Joe on the floor beside me and I held onto his hand with mine.

Rialto Street itself is only 20 feet wide, and more than the grade, its narrowness is what makes its descent risky. As they creep down the hillside, vehicles have to hug the shoulder to give opposing traffic room to pass. After weeks and months walking up and down the staircase my body became accustomed to the rigor of the ascent. I began to know its features thoroughly: the tags scrawled on the concrete and shattered glass in the undergrowth, layers of shale beneath the ivy clinging to the cut-away hillside. I could anticipate the body of a pigeon lying on one of the steps about halfway up, could negotiate the terrain so my foot would avoid its soft corpse. Even so, the street’s confined nature meant that it never stopped feeling perilous. One hot afternoon in late July, Joe decided to ride his bike down Rialto. As I watched him tip forward over the hillside, tapping on and off the brakes, anxiety welled up in my chest. I did not think he would tumble all the way down but I knew there was nowhere else to go. I took the stairs and met him at the bottom.

![]()

By August a couple had moved into the rental next door to Sally’s. From the upstairs window I would watch the woman, Esti, as she put in a garden for the end of summer. With a shovel she stripped away long sections of grass from the soil, then sprinkled in seeds: Sunflower, she told me, Swiss chard, kale. Whenever Esti went walking around the neighborhood she would look for other plants to add to her garden, and as the summer ripened into fall, she took trimmings from succulents off the sidewalk and planted hen-and-chicks, tightly wound rosettes that promised to multiply. She broke off seedpods and dried husks, keeping them in glass jars until the next planting in spring. Sometimes she went out to the backyard to pick her orange nasturtiums and eat them with her fingers.

Esti had lived many lives, she told me, past lives compressed into one, and she doled her stories out to me like sweets pressed into my palm. There was the time she had lived in an empty storefront with only a sleeping bag and a Bunsen burner. Another year she had lived out of her car, a hulking SUV she fantasized rolling down Rialto, shot full of arrows and set aflame. Esti had recently moved back to Pittsburgh from Asheville, and she talked about her mountains, how much she missed them, along with the fireflies and their secret flashing codes. When she first moved back to the city she said it was like the buildings and streets had moved too fast and she could feel the air reverberating at an unbearable decibel, a pent-up bottle of summer heat relieved only when the sky opened for a good rain.

Rialto Street is also called Pig Hill, after the animals that were herded up from Herr’s Island to be slaughtered in the packing plants on Spring Garden Avenue. At the time, Rialto was called Ravine Street, and in photographs from a century ago it looks like slurry. In the background of those pictures one can see the smog from the oil refineries and saw mills on Herr’s Island. Now Herr’s Island is called Washington’s Landing, and it is the site of identical condominiums, each one adorned with a red turret, and a marina with boats bobbing on the pier. That first spring we were together, Joe and I had ridden our bikes along the length of the island and I had seen swallows flitting over the water. The following year I went back alone. Only the shouts from a rowing team punctuated the quiet, and the enveloping silence seemed to amplify my solitude. I was in a place that was not intended for me.

A few weeks later, Esti had a yard sale and invited all the neighbors. I set up a clothing rack that teetered on the uneven ground, heavy with clothes I had imagined were suited to my body but I never wore. I sat on the clean grass and watched as Troy Hill women stacked cardboard boxes of books for people to peruse, bags of yarn tumbling forth, house plants and rolled-up rugs and records. Esti flitted back and forth from her house to the yard, handing out plates of food and bottles of beer, and bringing out more of her belongings to sell: old cooking pots and jewelry and biscuit tins. I wandered over to her table and noticed a bracelet made of interlinking stones shaped to look like scarab beetles.

“It’s beautiful,” I commented, picking it up and admiring it in the light.

Esti took the bracelet from me and fastened it on my wrist. “This was my grandmother’s,” she said. “You can have it.”

She waved away the money I offered her. I smiled, touched the bracelet on my wrist, and looked over at Joe in his yard. He stood next to a table where he had set out the last of Sally’s things: a few books, dusty lamps, and a broken turntable. I watched him for a long time, waiting to see whether he would ever see me.

Eventually, Esti and I would move away from Sally’s together. We became housemates in a blue three-story with morning glories trumpeting in the yard and a horseshoe above the highest window for luck. The neighbors say the man who used to own the home had grapevines stretching over a trellis in the backyard. They still grow along one of the fences and in the abandoned yard next door, bursting with sweetness even though they are less flesh than seed. The birds like the grapes that have gone rotten on the vine, and on warm dusks they fill up the yard with their chatter, flirting and fluttering and swaying drunk until nightfall.

The last days I was with Joe, I bought crocuses and gave him half to plant in Sally’s yard. They were scattered carelessly with only some loose soil cast over them, and I doubted they would make it through to the other side of the year.

As I thought only of what I had given away I failed to remember my own bulbs I had planted in my own backyard. Then one spring morning I found them, purple and yellow, coming up from the mud. When I stooped to look at them more closely I noticed their insides resembled the architecture of cathedrals, and I remembered how I had been careful to plant them deep enough to protect them from frost, yet not so far below that they could not find the light. As I dug I had found other bulbs that had been planted there before, tulips and hyacinth and daffodils, and I was careful not to disturb them, not to destroy them through my imposition, in a small act I only realized later had brought me closer to my reality.