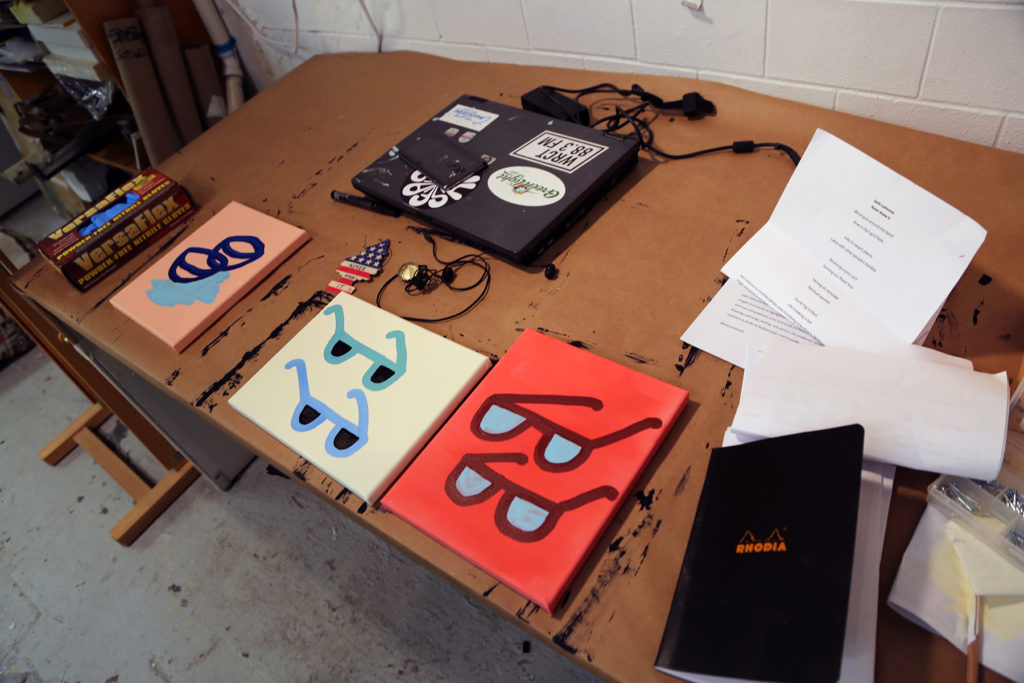

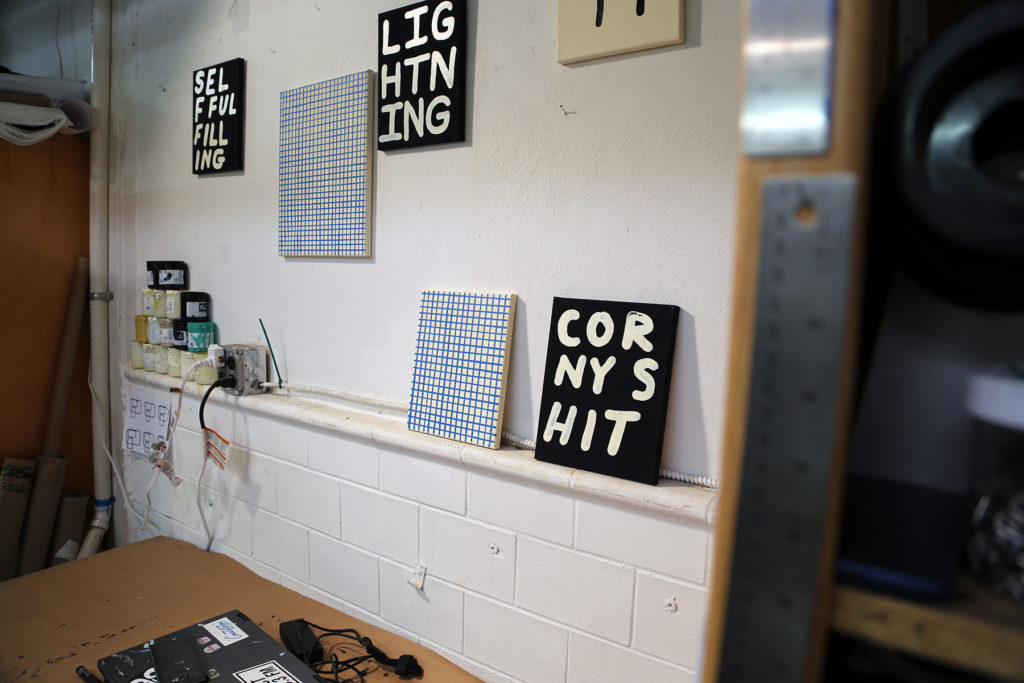

SO OVER IT. CORNY SHIT. RILLY GOIN 2 B OKAY. SELF PRESERVATION. Alongside graphically simple renderings of mountains and rivers, glasses and contact lenses, it’s the deceptively straightforward phrases, applied in a uniform, rounded font, that dominates the recent paintings of artist Seth LeDonne. Drawing on a history of zine making and self-publishing, LeDonne’s new work is intimate and inviting, accessible and approachable, and often funny through a sometimes acerbic wit.

On January 7, 2017, LeDonne will exhibit new work created over the winter in How To Get Back, a solo show at The Mine Factory. We dropped by Radiant Hall in Lawrenceville for a Studio Visit with LeDonne to discuss his recent exhibit at Bunker Projects (a two-person show with Natalia Gomez, The Glassblock’s The Object contributor), the appeal of using language in art, and the painting paths that sometimes lead to unintended phalluses.

David Bernabo: You are just coming off a two-person show at Bunker Projects. Can you talk about the inputs to that installation?

Seth LeDonne: With the Bunker Projects show, I was taking advantage of the chance to do an install. Oftentimes, I’ve hung things pretty conventionally. With the work [for that show], I was taking the chance to pull from a queue of ideas I had for writing and put them into a visual form—things that might have been segments of longer poems, but also might have been half of a tweet. I was trying to let those things be as special as they could be. A lot of times I don’t fully commit to those ideas. Even if people laugh at it or share it, it is not accumulating. I’ve used an app to delete my entire Twitter before. So, you have zero. I don’t work things to end up there. That’s why I don’t use Snapchat. I’m not going to produce content that’s temporary.

But there is an importance to everyone’s creative web presence. If you feel that you’re a non-artist or if you feel that you are a creative person, who you are on the Internet is a weird parallel to who you are in real life, because you can still amplify good things and say fuck off to shitty stuff.

“I’m careful with my language. A lot of it is walking a line between being vulnerable and being a hot mess.”

DB: With the Bunker Projects show, did it help that you were able to place so many pieces side-by-side? Did the setting of Bunker let you play with simplicity in designing the installation?

SL: Though I had an entire room, it is still kind of a limited space. Some of the ideas that I initially had about compartmentalizing the space—I had to accept that [the installation] was going to be a fluid space, way less formalized. It became more decorative, but that gave me more freedom to hang the work. But that’s a decision that I made the night I started painting gallery. I like when major decisions are made very clear by someone else’s revelation and not your own. You can really suck at collaborating, but really good at taking advice.

DB: What is appealing about using language?

SL: I do write; I’d say I’m a writer. There’s this way that people combine words and images with sequential art—I totally can’t and won’t do that—but I like to see words as objects. I don’t have the patience for real hand lettering, but I do like all the civilian graffiti or endearing signage. I do connect with that earnestness. The “font” that I’ve been working with for a while took a lot of failure to arrive at. I know why the roundness matters. I know why I’ll never be a person that uses serifs or the chisel-tip marker. I want my lines to be very MS Paint. I want the aesthetic feel of text to be the feel of my hand, but also sort of mechanical.

The words—I’m always looking for a chance to use them. Maybe I can create an image and use a word with that. That’s sometimes worth the risk, but often not. In the past, when I was doing a lot of drawing, a lot of times [text] was a punchline to repair something or to validate the drawing. Then you’re like, why don’t I just use the punchline. When it’s just text, that’s all you get to focus on.

Putting words on a canvas is the second phase for validating a text. I’m careful with my language. A lot of it is walking a line between being vulnerable and being a hot mess. I like catchphrases. I like slogans. I like texting. There is that quality to [the work]. Casual conversation and applying that to something a little deeper.

DB: I like the openness of the phrases that you write. It’s a little self-help-y.

SL: Yeah, it’s often self-help-y. I try to balance that out sometimes. It’s odd. The self-help-y ones are often expressing the deeper—they’re the ones that are coming from darker places. And the ones that might seem bitter, they’re the funny ones. There’s a catharsis in some of them.

DB: Whenever I sit with the work, there seem to be a number of paths that could be leading to it, and it’s easy to fill that in, allowing for a very personal path to the work.

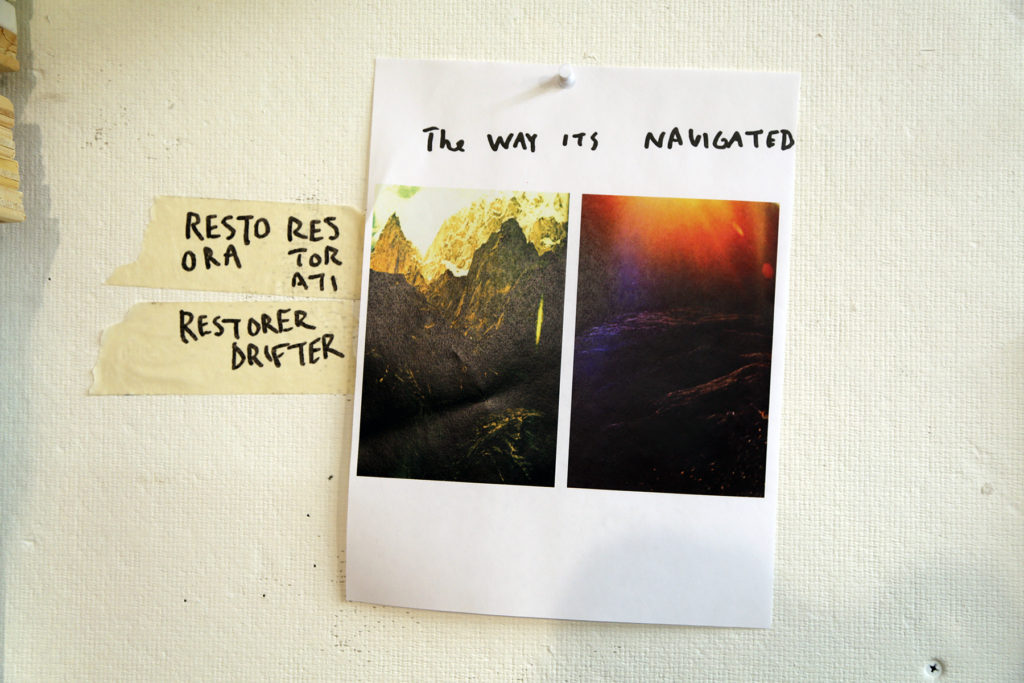

SL: I relate to that in two ways. The title of the [Bunker Projects] show is Never Knew It. My parent’s generation, at least where I’m from, even if someone wasn’t super patriotic, they would feel that of course the government is good, of course our country is great. I feel like in our generation, fewer people are blindly patriotic or patriotic by default or are without questioning. Being patriotic, I never remember feeling that way. So, I thought that was a good name for the show since it can allude to other things.

The next show is called How to Get Back. I mean it in a directional way, but a day later I was wondering if someone would interpret that as how to get back at somebody, how to get revenge. I never would think that. It’s like when you draw something and it ends up looking phallic, but you didn’t think it would. Like someone points out, “hey, that clock tower looks kind of phallic,” and you’re like, “fuck.”

At the artist talk at the closing of this show, I touched on how I hung the show the Friday before the election. The artist talk was two weeks later. At the time of hanging, I was happy with the work. By the time the artist talk came around, I realized how much of myself I put into it and how the work was reflective of who I want to be as an artist and who I want to be as a person. The messages were things that I was comfortable having serve that purpose.

DB: What kind of messages?

SL: Though the messages may not have been intentional, they were oftentimes light-hearted, restorative, and consoling.

Seth LeDonne’s solo show How To Get Back opens at The Mine Factory on Saturday, January 7, 2016 from 6:00 to 9:00 p.m.