Since its founding in 2010, the always-potent VIA Festival has shaken Pittsburgh with its pairings of cutting-edge electronic and dance music with video and installation art, lectures, and diverse technological adventures. In collaboration with some of the city’s most exciting cultural organizations and institutions, this year’s VIA—the seventh for co-founders Lauren Goshinski and Quinn Leonowicz—is rolling out four days of avant-garde programming: A master class workshop led by Brooklyn duo FlucT, who use exaggerated physical movements in performance art that “[meets] the male gaze [and] then violently [pokes] it in the eye.” A Mr. Roboto Project barrage of experimental sounds that ranges from droning to abrasive (cue up Henry Mallard’s “Modern Artsy Noise For Pittsburgh People Under The Age of 12” for a taste). A riff on the classic “Exquisite Corpse” parlor game in which participating artists use coding languages to “anticipate and subvert” each other’s work. Not to mention a futurist film collage screening, a sculptural garment tableau performance, and, of course, a three-night-long main showcase featuring, among others, legendary hip-hop artist Rakim performing 1987’s Paid in Full in full, Brooklyn DJ and trans activist Juliana Huxtable’s queer New York party Shock Value, and the Pennsylvania performance premiere of post-punk group ESG, whose 1981 track “UFO” stands today as one of the most sampled songs in history. And this is just a slice of the schedule.

This year, VIA’s collaboration with CMU’s Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry has produced Weird Reality, a symposium dedicated to “virtual, augmented, and mixed realities“—think VR headsets—that has captured a lot of attention.

But another program, Saturday’s artist talk and sound showcase Mothership: The Future Is Female, in partnership with the zine Women in Sound, and taking place at the Ace Hotel in East Liberty, is a particularly shining star in the festival’s constellation. We spoke with four Pittsburghers involved with Mothership, from curating to presenting to performing, to learn more about the impetus behind it and the work they’re doing in the city. Read our conversations with Lauren Goshinski, Anqwenique Wingfield, Madeleine Campbell, and Molly Burkett below—and grab your tickets for all of VIA’s scheduled events here.

![]()

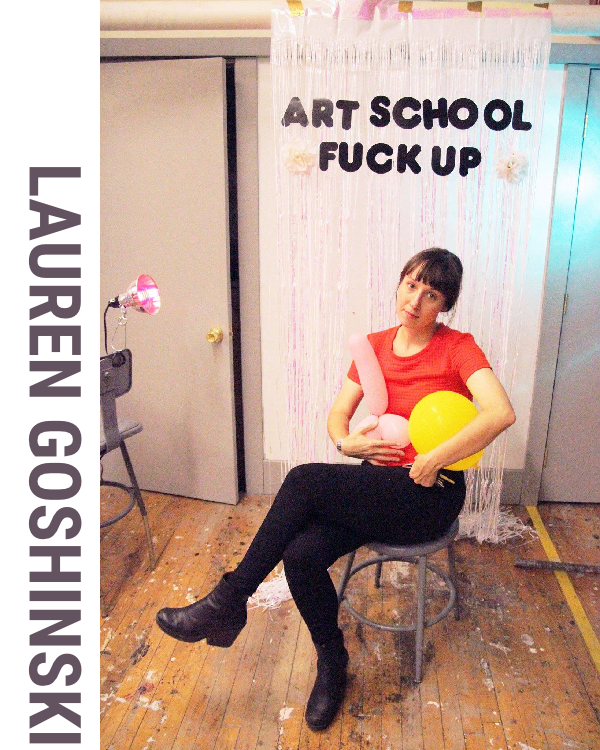

Lauren Gohsinski is a curator, event producer, and artist. She is co-founder/director of VIA.

Adam Shuck: Why did Mothership: The Future Is Female and the VR salon Weird Reality come to the fore for you this year?

Lauren Goshinski: They’re both extensions of projects I’ve been working on for VIA, or for events that I’ve put together over the years, and they’ve crystallized in a really big way this year.

Mothership is an extension of an industry women panel that we started last year as part of VIA. There are a lot of us who agreed that it’s time to start getting Pittsburgh women in the music scene together to have more of a public presence, and Mothership is a larger extension of that. This year it seems to be such a powerhouse line-up, but it’s coincided with the research and reissue of Betty Davis’s Columbia Years record [The Columbia Years 1968-1969, from Light in the Attic Records]—there are a lot of things that were all happening at the same time, kind of like the stars aligning, for this big daytime event.

I’ve been working closely with Madeleine Campbell—we featured her launch of Women in Sound as part of VIA Festival last year—and that’s a partnership we’d like to continue. [Read below for our conversation with Campbell]. She curated the Women in Sound showcase of the Mothership extravaganza and helped curate some of the local artists who are part of the panel discussion, which she wanted to make sure was a day-time event that families could come to, that it was donation-based, and so on. The panel is definitely inspired by the legacy of Betty Davis, [who] still resides right outside of Pittsburgh, and if you know the history and legacy of Davis and the difficulties that she’s gone through, then a lot of the other speakers make sense.

This is something [for which] I’m actively trying to put pieces together every couple months to gather energy around it, and as far as larger groups of women in Pittsburgh who work between music and nightlife and digital and interactive arts, we’re all talking on a regular basis.

AS: What are you hoping VIA attendees get out of the Weird Reality VR salon?

LG: Weird Reality is co-curated between me and Golan Levin [who is, among other things, director of CMU’s STUDIO for Creative Inquiry], and it’s part of my fellowship there. We’re definitely trying to come at it from two different ends: The first is just access to this gear—because not everybody can just go drop $600 for an Oculus, you know? But it’s not just about access to cool, emerging technology, but about being engaged in conversations like: What are the stories that we’re telling with this technology? What are the artistic potentials of it? And who’s creating it? Who’s being brought to the table?

I think we probably have one of the more, if not most, diverse line-ups [among] tech and VR conferences. There are a lot of amazing artists and filmmakers who are doing this—it’s just that a lot of conferences just, kind of, pick the white dudes at Google. We reached out through our networks to find people who are taking experimental approaches, or trying to address certain issues, through the platform of VR, which is still inherently a technocratic, white, male-driven industry. But VR is at a really interesting tipping point right now because it’s expanding so quickly. We want as many people as possible to help push and drive where this tech is going [and] be a part of this conversation about what it’s used for and why it would be meaningful in people’s lives.

![]()

Anqwenique Wingfield is a classically trained singer who performs in a range of genres, the studio manager of BOOM Concepts, education director at the Opera Theater of Pittsburgh, and a board member of the Pittsburgh Center for Creative Reuse.

Adam Shuck: Tell me a bit about your work and your career in Pittsburgh.

Anqwenique Wingfield: My career has, I think, taken a non-traditional path, crossing genres and creating new works that bring audiences together to meld and blur the lines that we place between different kinds of art—they separate people, as well. My work is [about] trying to reverse that, to bring those artists and audiences together.

One example is an artist collective I started about three years ago called Groove Aesthetic. It was created as a platform for performance artists, and those across disciplines or who are versatile across genre, to have a space for collaboration to play around and blur those lines. One of our performances, Bach Boom Box, was an intentional meld of classical music and hip-hop. We did everything from Bach duets with free-style hip-hop, to contemporary ballet styles of dance, to string players improvising and playing to a more hip-hop beat, and all kinds of things in between.

I like to take a classical repertoire and juxtapose it with other genres, like jazz and hip-hop, and play around with instrumentation, instruments usually used for jazz versus classical music, mix them together and see what happens. But I’m also a working musician in very traditional ways: performing for weddings, or really traditional jazz gigs, or roles with smaller opera companies here in the city.

AS: VIA offers a lot of programming around the idea of pulling up unrepresented or underrepresented people and practices. How do you see that prompt, and how does your involvement with VIA speak to that?

AW: I think it’s really important to always be considering marginalized voices. In my work at BOOM Concepts, we specifically try to create a space where people who have been marginalized, who feel like their voices have not been heard or who do not feel safe, can create work that represents them.

Coming from a classical, operatic background, I always felt like I wanted to see more representation of myself, people like me, or people of color, in opera and classical music as an art form. Many classical art forms struggle with that, from opera to ballet to chamber music, and so on. Within our creative ecosystem in Pittsburgh, I’ve felt like a bridge to help connect people with organizations and companies, and as someone who lives between different communities, I can help carry people along that bridge, helping to make sure that we have representation of people of color, women, queer people, trans folks, at the table—not just in creative spaces and spaces where we’re creating art, but in policy making and in activism and [in positions] to make decisions about people’s lives.

Most recently I’ve embarked on an endeavor called Sirens & Queens, which is typically a concert recital series celebrating Black women in classical music—celebrating great singers like Leontyne Price but also, especially, celebrating Black women composers. I’ve done a lot of research, pulling out tons and tons of repertoire written by Black American women composers that’s just so beautiful but that doesn’t get performed and doesn’t get celebrated as much as our traditional composers. This concert series intentionally pulls forth this work and talks about these women, their lives, and their motivations to write these works. That’s my little space, an ode to Black women on whose shoulders I stand, and to make sure that we’re making space for this work just as much as we do for Bach, Mozart, Copland, and all these other great composers.

It’s so important how VIA—not just this year, but over the years—made a point to make sure that women have a voice and that we are expressing ourselves freely. I think people have a lot to say, and I think there’s been a trend traditionally of just not listening to people of color or to women, or not valuing their voices as much. There needs to be an intentionality around how we create that space for people to have a seat at the table.

AS: What has the response been locally to the work that you’re creating?

AW: I’ve found that people respond positively to my work, but I also accept and welcome other artists or other people who are very critical of work as well. Fortunately I’ve never had anyone come up to me after a show to say, like, “I hated it!” [Laughs].

My goal in performance as an artist is to always give of myself as much as I can in the best way that I can, and that means that I’m very serious about bringing a well-prepared and well-thought-out product to my listeners. I care about how they receive the work and in what context they receive the work, [including] the ambiance and the environment that they’re going to walk into to experience the work. This is all part of being a creative entrepreneur, an artist—be considerate and think about your audience in that way.

Now, there’s also the other piece to this, where the content is concerned: You can’t care too much what people think, right? You have to be able to create freely, and whatever comes out, comes out. [It may not] satisfy, or be for, everyone who receives it, and you have to be open to that as well.

I’m working on a new project composing an opera, something I’m really excited about, because I’m learning to be a composer; I’m learning about composition and what that means for me and my creative process. But I’ve definitely had moments where I’ve been scared to put something down on paper, and I’ll have to tell myself, “No, people need to be accepting of all that I have to give [even though] it may be different from what people have traditionally heard from me.”

AS: On Saturday you’re participating in the Mothership: The Future Is Female artist talk but not performing, right?

AW: It’s kind of an intentional choice. This is a transitional season for me: I’m doing more creative writing and have been intentionally not doing a lot of performing. My schedule’s changing and I’m readjusting my life in different ways. But I’m excited to be able to talk about my experiences, which is rare. People often see me perform around the city at different events, and not often am I very comfortable talking about my experiences—but I’m trying to be better about that. I want people, especially young people and young women, to know that there is so much possibility and agency that you have, so many ways to get support for your work. So I’m happy to be sharing my experiences with that.

![]()

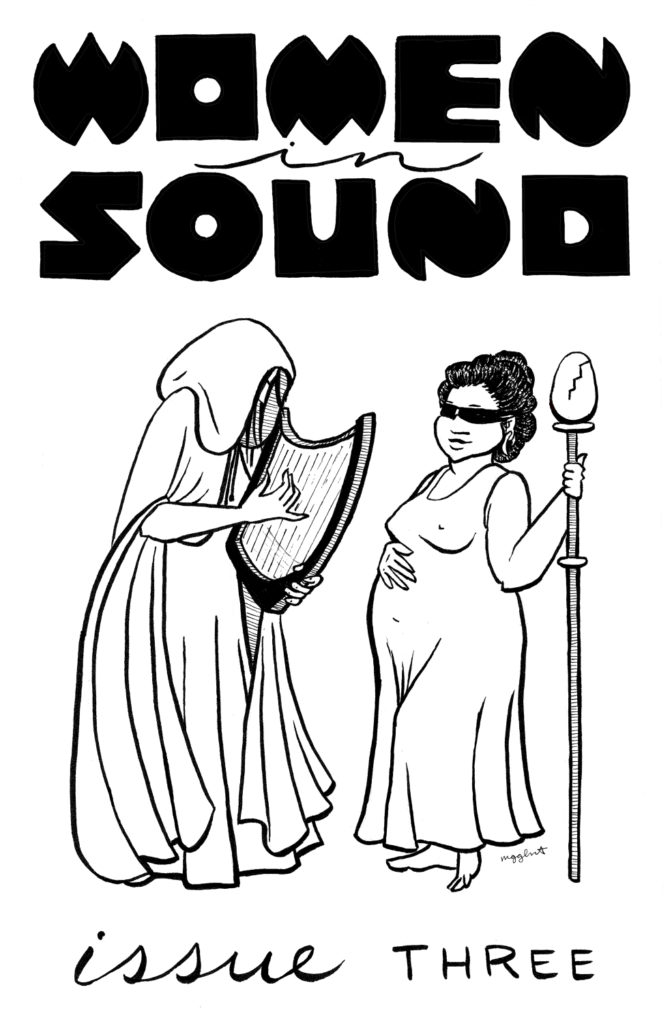

Madeleine Campbell is a recording and mixing engineer and founder of Women In Sound, a zine whose third issue is being released in collaboration with VIA. Campbell co-curated the Mothership: The Future is Female showcase.

AS: How did you come to be involved with VIA?

MC: I started Women in Sound last year in an effort to recognize and celebrate some of the women in my field. I kept getting the question, “Wow, why are there so few women in the studio or running soundboards at venues?” And I got kind of frustrated because I realized that there are a lot—they’re just being totally ignored. So I mentioned [Women in Sound] really casually to Lauren Goshinski, and she was the one who suggested that we do a showcase for it at VIA last year. The first issue came out with VIA 2015, another issue came out this past May, and then we knew we wanted to collaborate again this year. So for the past couple months Lauren and I have been putting our heads together and thinking about how we can incorporate some of the themes of VIA with some things that are going on in her head, in my head, and are reflected in this issue of the zine.

[Goshinski and I] had started talking about the Betty Davis documentary that’s in production now, and a dear friend of mine, Danielle Maggio, who’s a PhD candidate in Ethnomusicology at Pitt, has been studying and teaching on the music of Black women in the United States. She’s really knowledgable about the history of and the impact that Betty made on music throughout the 21st century. So the three of us got together to talk about the documentary and what’s going on with Betty. And we just realized: Betty is a Pittsburgh resident; and she’s been living here for the last three and a half decades! People either immediately know who she is—and recognize her genius and brilliance, that she was truly one of a kind, and paved paths for so many artists—or they have no idea who she is, and they think I’m talking about that actress named Bette Davis.

So often, women’s creation and labor and the work they bring into the world is unrecognized, uncelebrated, and often uncredited. So, without focusing too much on, like, “Wow, a lot of women have been truly fucked over”–we don’t really want to frame it like that, but instead celebrate the brilliance of so many women creators around us, so that Pittsburgh is being represented, and connected [into conversations] on a national and international scale.

AS: Is the focus of your zine women who are in audio production and management, or also women in performance and artistic creation?

MC: It’s definitely a mix and has been consistently for all three issues. There are audio engineers, live sound engineers, producers, beat-makers, DJs, performing artists—it’s a big range of women. I really want to focus on all facets of live and recorded music and also at all levels of production, whether you’re recording albums in a garage with two microphones, or at great historical, legendary studios. To me, it’s all beautiful, and it’s all interesting. I just want there to be a lot of representation: a lot of different women and a lot of different places doing a lot of different work within the field of sound at all different levels.

AS: Women in Sound seems to be about representation of—to share and amplify—women who are working and producing and creating. But how do you see it as inspiring new women to come to this field?

MC: I’ve worked in large studios and am currently in the process of building out a small studio of my own. And a lot of audio literature—not only is it not encouraging and welcoming and inclusive to women, but really to all beginners in general. It assumes a really advanced level of knowledge, and that’s intimidating. I don’t know how you can encourage more women to become active in this field if they can’t even cross the threshold of knowledge to get in the door. A lot of audio literature speaks in a language that even I still struggle with, and this is my job! I can’t speak for all women, but I still battle these feelings when reading gear reviews, or when I’m reading about someone’s process and I’m like, “Oh. I don’t know what that means.”

My dear friend Heba Kadry, who’s a master engineer in Brooklyn, she was in the first issue [of Women in Sound] and one of the first questions was, “What is mastering?” Because you can’t really gather much from a master engineer’s interview, talking about their process and their work and their achievements, if you don’t even have a base level knowledge of what it is they do. I just want to demystify as much as I can right off the bat to establish a more even playing field for people to even begin having conversations and start generating their own ideas.

I just want my field to be more inclusive, ultimately. I feel like even in my short time working in professional audio, I do see a lot more representation, but that’s because I’ve worked really hard to find it. And the audio field has a lot of work left to do. There’s so much focus on the history of the greatest albums ever recorded, or glorification of gear, and I get that, you know—I also love gear. A lot of it is really beautiful and worthy of extensive analysis and critique. However, I want to refocus the power back into the hands that are using the gear rather than just the machine. I think there’s so much dwelling on achieving sounds that already exist, and I’m more interested in looking forward and trying new techniques to find what hasn’t already been established yet.

AS: I don’t know the audio field at all, really. Can you give me a sense of what that ecosystem is like in Pittsburgh right now?

MC: I really feel like it’s on the come-up. I feel like good things are happening, and I think the VIA Festival is a huge reason for that, and for music production in Pittsburgh in general. I’m really excited with the direction that it’s going. There are some really beautiful, well-established, large, high-cost studios. I’ve also recorded several albums in my friends’ Polish Hill garage on Gold Way this year with very little resources. So both ends of the spectrum are represented. My hope is that we can bridge the gap between those two, and I feel like we’re moving in that direction generally. I’m moving into my own studio space in November, and it’s called Accessible Recording, for that reason—I want people of all means to be able to make meaningful recordings that are important to them.

![]()

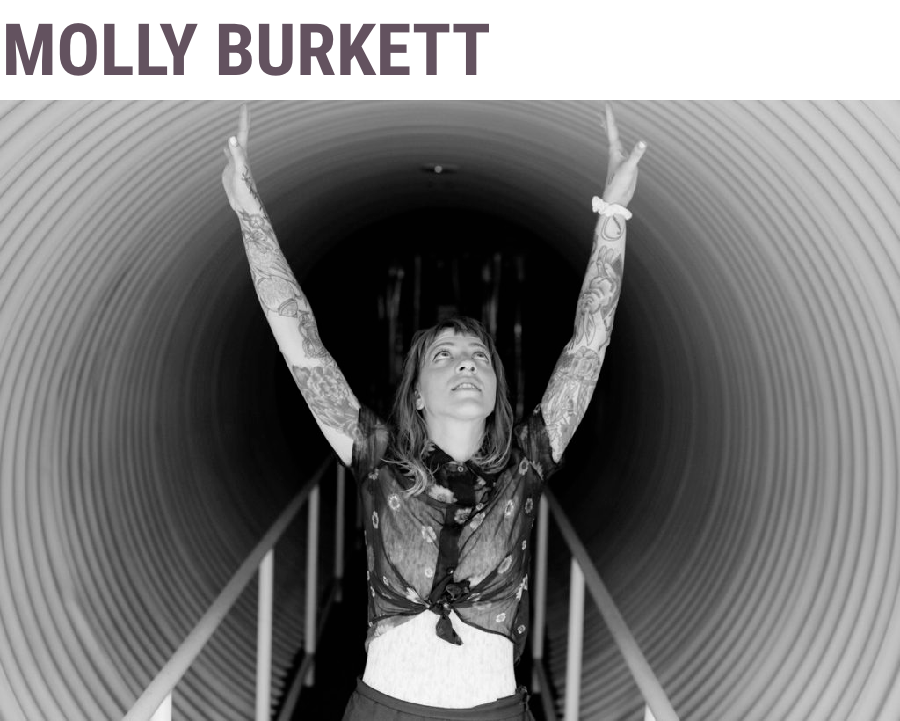

Molly Burkett is a musician and sound producer who performs as Nancy Dr0ne. Her EP Subformation was just released on La Squadra Records.

David Bernabo: How did you get involved in music and sound?

Molly Burkett: Music has been a huge part of my life. I started piano lessons when I was super young, and then I picked up a guitar, but it seemed like I wasn’t satisfied with what I was making. A lot of it had to do with not feeling confident enough with expressing myself: I thought that I had to be conventional and that I had to do things in a certain way. As I’ve gotten older, and the more I got into electronic music, it’s been very obvious that I can do anything. It feels so much better than trying to fit within certain standards.

DB: Does your Subformation EP, released by La Squadra Records this past August, consist more of live playing and layering or edited sounds?

MB: It’s a lot of live stuff. The editing process isn’t too huge. I edit the sounds, I use effects—bend them, morph them. But I like to edit live. So I’ll map different effects to different MIDI controls on another controller that has knobs and have the freedom to give each set a different flow—to feel to it versus having one song that sounds the same every time.

DB: Are the songs more templates than highly structured works?

MB: Yeah, definitely more template format.

DB: Can you describe the creation process?

MB: When I open Ableton, I usually pick a sound. I’m familiar with keyboards so I’ll use [them] to map something out that I like. Or I’ll start with a drum track. I like really dissonant drum tracks, so I’ll make a few that I like and mash them together and then build off of that with melody. But all the pieces have those few elements to them. I usually have 50 MIDI tracks open at one time. They’re pretty big files: I’m surprised the computer hasn’t crashed terribly.

DB: That’s always the risk, right?

MB: That’s the one frustrating part between the hardware and the way I learned music. I can’t always trust it. I can’t always expect it to not fail on me.

DB: I’m used to more acoustic instruments, but when I mess with electronic equipment, a lot of times the tools control what I can make. And then the process becomes how you can extract things that weren’t intended from the tools. How much do the tools control the range of possibilities for what you want to do?

MB: I feel like I’m maxing out from the pre-loaded samples that are in Ableton [Live, the music sequencer software], but there are still so many possibilities with it. Recently I added vocals to a lot of my songs. That’s one way that I went outside of the range that Ableton has to offer. I grew up singing a lot, so that was one thing that I was able to add that the computer can’t do. It makes the song very personal.

DB: Is it a gut feeling when you know an edit is done?

MB: Yeah, it’s an internal feeling. It’s like a meditative process for me. Whenever it feels like something is finished, I get a light feeling, a really good feeling, and it lets me move on to other things. Because I get really stuck on things when they are not perfect.

That happens when the translation is difficult from what I’m hearing in my head and what I want to get out. When it’s not coming back at me through my hands, it’s like, “What is between me and this software that is blocking me from producing the thing I’m hearing?” Sometimes it’s just about going with it and letting it be the feeling that you didn’t expect it to be. Then the song becomes entirely different than what I tried to make. So I try not to get hung up on the technicalities, but focus on the emotive quality in the music, and that’s usually when I have the most success.

DB: How did you connect with La Squadra for the release of the Subformation EP?

MB: I started playing [as Nancy Dr0ne] in February, playing two shows a month. I performed with friends from Aud Art and the Future Body Sound group and another friend, Kevin Bednar, performed that night. Kevin put me on Cosmic Sound, and we became friends and started swapping music. He asked me for a guest mix for his radio show. Then [La Squadra founder] Dario [Miceli] e-mailed me and said, “I heard your radio show. Can you give me a release?” So, it was really organic and out of the blue.

Getting to be released alongside people who are doing modular synth stuff and live coding, I think it’s a really cool showcase of Pittsburgh talent. It was great to be a woman on that label, too. I know Anna from slowdanger, and Alexis Icon was just released this month. So, we’re coming in and taking over. It’s really cool what Dario is doing.

DB: How do you find the local electronic scene?

MB: I feel really accepted as a woman in electronic music right now, and that’s an awesome feeling, because I came from a punk and hardcore background, and that was really masculine territory. I was finding that I wanted to do music but was hitting dead ends all the time. I would find these bands, we’d practice once, and stop. I was thinking, “Why can’t I just do this?” Even though [Nancy Dr0ne] is a world of isolation since I’m doing everything myself, it’s an extension of myself. It’s great to be a woman and just do this. I want women, especially young women, to know that they don’t have to be intimidated by this guy knowing more about sound engineering than her. A lot of it has to do with what resources you have. So, I want to be a resource, too, if I can. I like being hands-on, showing people things.

I want more women to be booked for shows. I want Pittsburgh to showcase more Pittsburgh female artists. And that’s why I’m so excited about VIA. It’s such a showcase of all kinds of arts and people and expression.

Women artists have so much to fight for just by being that gender. You have to fight against preconceived notions. And I’m not a very political person as far as music politics go, but I’d like to see Pittsburgh be a place where more women artists feel like they can play. I grew up as a woman struggling with disordered eating and disordered body image and mental health issues based on what the world expects of women. So, being able to go to this panel and see people who are successful and have done these amazing things with their music—it’s going to be a really awesome and safe space to have these discussions. A lot of people are fighting each other for no reason, but I don’t want to waste my time being angry. I want to put my time into important conversations.