Everything in the room is soft. Fabrics cushion the walls, painting them a palate of soft earth tones. The scent of burnt matches and patchouli hangs softly in the air. We sit cross-legged in a circle on a rainbow rug, my classmates’ faces still dusted with dirt from a rousing game of Red Rover at recess. We end the day with the usual send-off song to thank all of the good spirits… or something like that. After, I run to meet my mother in the carpool lane outside, my brother a few strides behind. The first fifteen minutes are a breathless sharing of every detail of the day: “And then Willow and I built a fort and wouldn’t let anyone in but Wesley tried and we had to run away from him and make a new fort and—” My mother listens patiently, sipping a kombucha. The car smells strongly of fermented grapes. I wonder if she’s made one explode again.

“Did you finish your lunch today?” she asks. Paul and I both explain that we don’t like brown rice and we wish she would stop giving it to us.

“It has vitamins you need as growing kids,” she explains, turning the car off the busy intersection into a suburban Louisville strip mall housing a liquor store, a wine and tapas bar, and a Chuck E. Cheese’s.

I am the model Waldorf child. I wear dresses, sing songs to “fire fairies,” and only watch TV on Fridays. I am dramatic and sensitive and very insecure. I’m six, and my Waldorf education has permeated every part of my being—almost.

“Thank you for choosing McDonald’s! Can I take your order?” The smell of kombucha is replaced with the salty, fatty aroma of ketchup and french fries. We eat in silence the rest of the ride home.

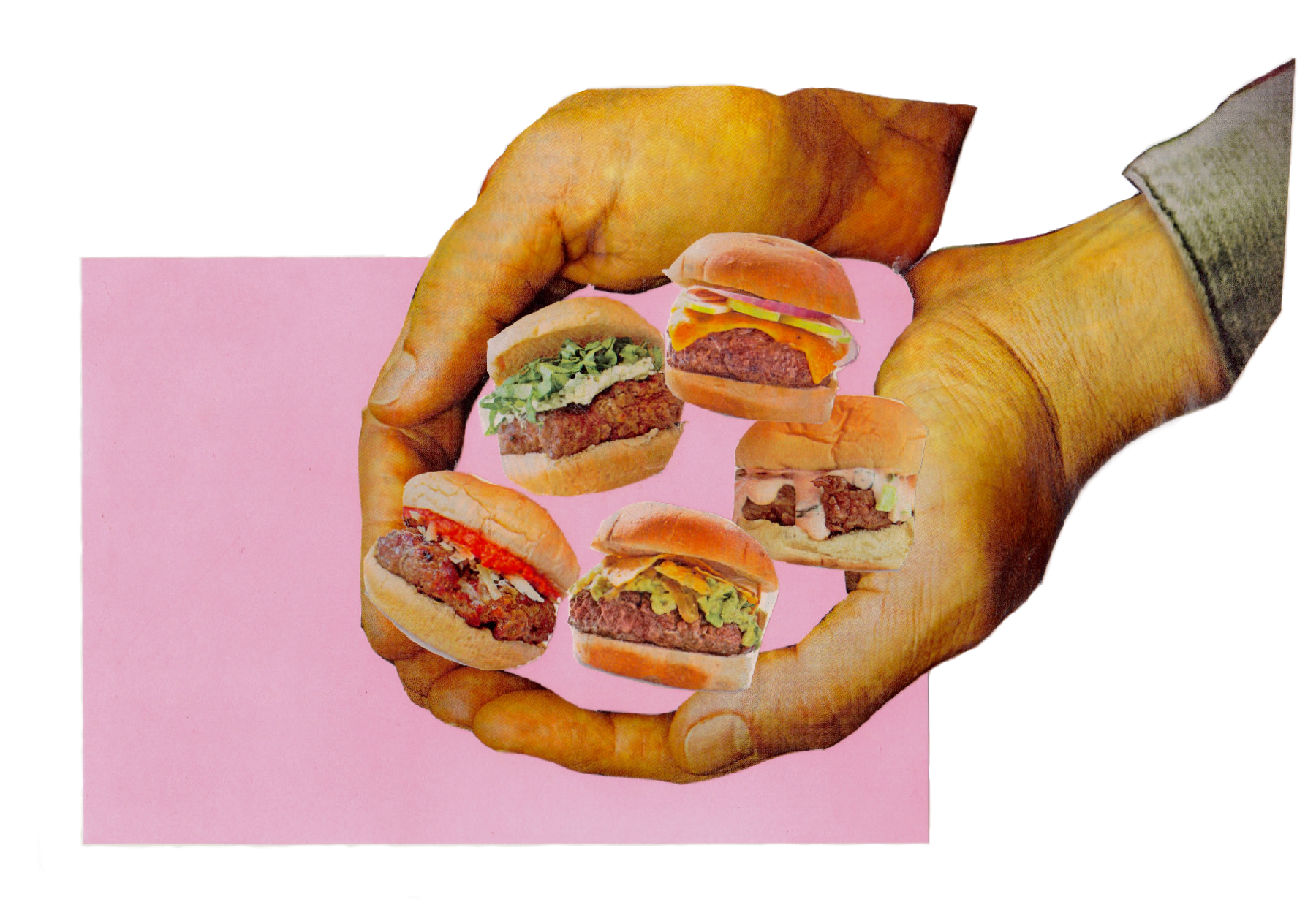

Junk food was a secret affair in my life, never spoken of but always loved deeply. Throughout my childhood, many things were hidden: televisions hidden in armoires, Disney movies hidden behind books on permaculture, frozen pizzas hidden beneath homemade chicken stock or leftover tempeh. In my family, we hid junk food—a rule that taught me how to be a sneaky kid. I would stash gummy bears under my pillow or Oreos in my t-shirt drawer, but cross the threshold and I was back in the land of green tea and Newman’s Own. I used to long for nights spent at my Dad’s house, eating Nutter Butters and watching MTV, or sleepovers where we would sneak out to eat Taco Bell and pretend to smoke cigarettes.

My mother, a woman who would speak at length about the benefits of spirulina, would sometimes forget to throw away wrappers from her secret cache of Dove chocolates. I once hid a package of cookies in my closet, only to find them all eaten by the next morning, unsure if I had gotten to them in my sleep or if they had fallen prey to my mother’s chocolate spidey senses. Meals in my house consisted of brown rice, tofu, and leafy greens, followed by a late night Dairy Queen run for Blizzards and french fries. One meal at the table, one meal in a moving car.

Sugar tastes better when it’s contraband.

![]()

I made myself break up with junk food my senior year of high school when my mom got sick. Our pantry was stocked with bulk brown rice, seaweed, and bushels of beets, and raw food dinners and dark green smoothies filled my mother’s stomach as her body fought the cancer. The late night DQ runs were replaced with homework or bike rides or anything that took the image of my slowly balding mother out of my head. I began to see that food could be as much of an enemy as it was a friend. My mother, the woman who took what felt like a hundred vitamins each morning and drank enough kombucha that if you pricked her finger, I’m sure the blood would smell of fermented tea leaves, still got sick. Had those french fries poisoned her body? Were they poisoning mine? Would things have been different if I hadn’t asked for that late night Blizzard? These questions plagued my eighteen-year-old mind as I choked down unseasoned seaweed. Around the same time, a boy used the word “chubby” to describe me. I looked in the mirror and saw every french fry.

Nearly a decade later, I’m back together with junk food, armed with a deeper understanding that my young adult insecurities were products of tumultuous relationships and not what I chose to dip in ketchup. I ate potato chips on a park bench in Istanbul while contemplating a move 5,000 miles away from home to “find myself.” I cried into a box of cake donuts on the floor of my Austin apartment the first time my heart was broken. And the week I moved to Pittsburgh, I lived almost exclusively on pepperoni pizza, cherishing the familiar pools of grease as I once again started over.

Food is what brought me to Pittsburgh. I made the choice almost two years ago, moving another 1,000 miles for a graduate program in Food Studies. I weighed down my blue Honda Civic with all of my worldly possessions and, nervous and excited, emerged from the Fort Pitt tunnel for the first time, devouring the skyline of the city I would call home. Buried beneath boxes of knick-knacks and trinkets was a blue gift bag filled with peach rings, original Lay’s, and peanut M&Ms, just in case.

Even now, as someone who thinks, reads, and writes about food all of the time, I find myself unconsciously grabbing that piece of candy in the Giant Eagle check-out line. This food I’d chosen not to analyze, nestled between a bag of kale and a carton of almond milk, greets me like an old friend, its industrial regularity familiar and reassuring. In a world where harmony and stability are often hard to come by, it’s undeniably comforting to know that some foods will always taste the same. Popcorn will always taste better with Raisinettes; the artificial flavors of Fritos or Cheetos will bring me back to childhood summers at the swimming pool; French fries will soothe a broken heart. Comfort foods, yes, but also consistent foods.

There is an unspoken expectation that a scholar of food shouldn’t enjoy these things, that they should know better. But thinking so purposely about food can be exhausting, demanding a critical eye to scan every supermarket purchase. Junk food can be a respite from all of this. And I hide junk food in a different way now, bringing handmade carrot cake donuts to a Food Studies potluck instead of a box of sticky sweet glazed Dunkin’ Donuts, or choosing poutine at Franktuary instead of french fries at McDonald’s.

“Chocolate is a vitamin,” my mother proclaims as we eat spoonfuls of soft serve ice cream on a California beach, a far reach from her past self. After nearly ten years of cancer-free life, my mother gleefully owns her love for chocolate. Now, when I visit, we pinch pieces of cookie dough and take sips of red wine together, allowing them to comfort and connect us. “Chocolate is a vitamin,” she says, and regardless of my food studies education or my own complex personal history with “junk food,” as we sit there, warm in the sun together, I agree with her.