Since the 1960s, speech local to Western Pennsylvania, referred to as “Pittsburghese,” has been tightly tied to regional identity, although exactly what it is and what it means to speak it have varied over time and from group to group. Pittsburghese emerged in the local imagination when Pittsburghers, once relatively isolated both geographically and culturally, became mobile—and thus in a position to notice that they spoke differently than people elsewhere, and that the way they talked could be linked with where they were from. Linguist Barbara Johnstone of Carnegie Mellon University has been studying Pittsburghese since the early 2000s and is the author of Speaking Pittsburghese: The Story of a Dialect. In her Pittsburghese Expertise series for The Glassblock, she examines the different facets of our local lingo, providing a deeper insight into why yinz talk the way yinz do.

![]()

It’s said that if Shakespeare’s Hamlet had been a Pittsburgher, the opening phrase of his famous soliloquy would be rendered as “or not”: Pittsburghers, after all, drop “to be.” Whoever thought this up was onto something about Pittsburgh speech, but it’s not that Pittsburghers don’t use the construction “to be” across the board—it’s that in some specific contexts, some native Pittsburghers use a grammatical structure that does not include to be, whereas many other Americans use a structure that does. To wit, the specific contexts are when using the verb need (and, for some speakers, want and like), and the grammatical structure is that of a verb “complement.” Let’s explore what this means.

You know more about the verbs you use than you may realize. You know not only what a verb means but also what is needed, grammatically, in order to use it in a sentence. To be more specific, you know whether or not the verb needs a “complement,” and what kind. You may be familiar with the difference between “transitive” and “intransitive” ways of using verbs: When it’s transitive, a verb must take on a direct object as a complement (“She walks the dog”), but when it’s intransitive, it doesn’t (“No, thanks, I’ll walk”). But these aren’t the only two possibilities.

Take the verb need. Normally, need requires a complement: We don’t generally hear need without either a direct object—“I need a drink”—or, in Standard Written American English, with a phrase on the model of to be verbed—“Coincidentally, this ten-year-old bottle of Bordeaux needs to be opened.” But in other varieties of English, there are alternative options for complementing need. In some parts of England, you’d hear people use a phrase on the model of verbing: “The wine needs opening.” In other parts of Britain—and in a swath of the United States that includes Pittsburgh—you’d hear verbed: “The wine needs opened.” What Pittsburghers (and other people throughout the Midwest) are doing when they say things like “The car needs washed” is using what linguists describe as a non-standard complementation pattern with the verb need. To say that a language form is “non-standard” simply means that it is not the choice we would normally see in carefully edited, formal writing—not that it is “wrong” in everyday speech.

Buses speak #Pittsburghese now, too. "Need vaccinated." pic.twitter.com/36HzDuobTz

— C Dubs (@c_dubya37) June 9, 2016

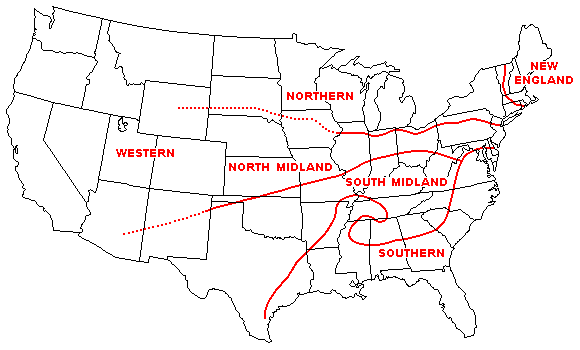

This need verbed non-standard complementation pattern found in Pittsburghese is often referred to as “dropping the to be,” suggesting, erroneously, that people first learn to say “The car needs to be washed” and then, out of laziness or sloppiness, leave a segment out. But people who say “needs washed” did not say “needs to be washed” in some previous phase of their lives. Indeed, many are not even aware that there is another way besides verbed to complement the verb need. The same is true at a larger timescale: In the history of American English, the need verbed pattern did not arise because people started dropping to be in the need to be verbed pattern. Rather, as the dialects and varieties that descended from older Germanic languages evolved separately in different places, they drifted apart. Settlers from other parts of the English-speaking world brought with them both need to be verbed and need verbed, and need verbed was the form that those settling in the Midland region of what became the U.S. brought with them from Scotland and Northern England.

Some elements of Pittsburghese have fallen by the wayside: You don’t hear “diamond” used to mean town square any more. Some elements are in danger of extinction: Even people with noticeable Pittsburgh accents don’t say “dahntahn” or “aht” as much as they used to. But the needs verbed construction is alive and well, in Pittsburgh and elsewhere. The woman staffing the home improvement kiosk at the farmers’ market asks if your place needs renovated; a plumber’s invoice notes that the circulating pump needed replaced; a neurologist talks about symptoms that need treated. People who use it are largely unaware that it sounds non-standard to anyone. And if needs verbed users do find out they’re in the minority, it often happens when they go somewhere outside of the needs verbed area—to move for a new job, or to attend college, or on vacation, for example—and a bemused friend or colleague points it out.

In fact, it’s possible that you are just now learning, from this article, that needs verbed isn’t the way everybody says it. And if so, keep right on using it. Needs verbed needs preserved.