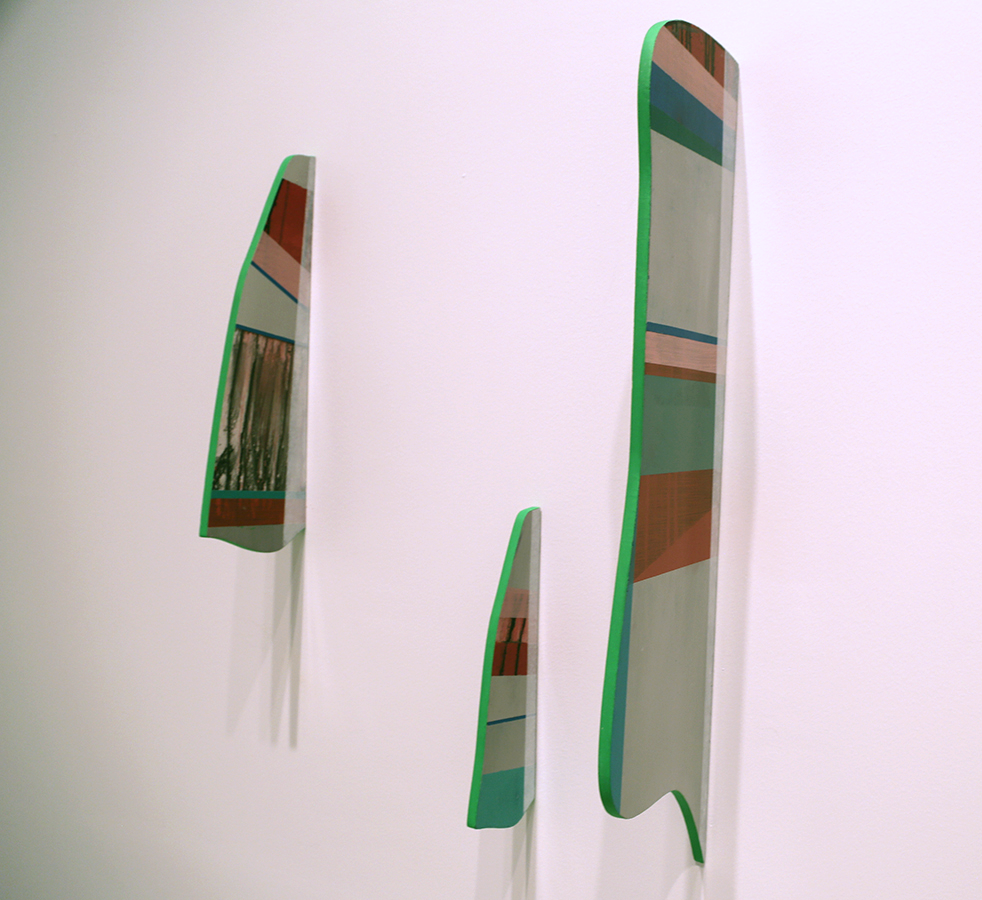

Facing the entrance is Laurie Trok’s clever suite of wall pieces, thin fins of wood projecting straight out, creating the illusion that their neon green edges are mere lines applied directly to the wall. Its neighbor, Katie Murken’s Continua, uses phone books dyed with rich, bright colors and stacked high into columns. Seen at a distance, they appear minimalist in conception; up close they reveal velvety, rainbow surfaces. To me they suggest core samples taken from sedimented layers of historical information, rendered archaeological by the emergence of digital media.

Bright, saturated colors continue to punctuate the show, appearing in abstract paintings by Mark E. Weleski and Mia Tarducci, and in sculptures by Michael Walsh and Daniel Roth. Roth’s large floor piece is serious in intent and humorous in execution, resembling a finely-crafted piece of space junk. Its surfaces are painted cool colors but its edges are trimmed in fake fur, which animates and anthropomorphizes the work. Roth described imagining the black tufts as an alien life form, a mold or parasitic moss, finding this hulking, broken object and calling it home.

Bright, saturated colors continue to punctuate the show, appearing in abstract paintings by Mark E. Weleski and Mia Tarducci, and in sculptures by Michael Walsh and Daniel Roth. Roth’s large floor piece is serious in intent and humorous in execution, resembling a finely-crafted piece of space junk. Its surfaces are painted cool colors but its edges are trimmed in fake fur, which animates and anthropomorphizes the work. Roth described imagining the black tufts as an alien life form, a mold or parasitic moss, finding this hulking, broken object and calling it home.

There are many other strong works, including satisfying paintings by David Stanger and Todd Keyser. But it is precisely the power and variety of these formal achievements that bring out most forcefully the overall conservatism of the AAP selection. Among sixty-three artworks, not one deploys new media. There is no film, video, VR helmets, or screens of any kind. There’s no hint whatsoever that the internet exists. As my editor put it, “There’s nothing plugged in.”

To anyone familiar with the Annuals, this will come as no surprise. Curator of the 2005 Annual Terry Smith—the éminence grise of contemporary art—observed that while AAP members produced quality work in traditional mediums, they offered little or no installation, process work, performance, or digital media. “Much more of it should be encouraged in the AAP competition if the exhibit is to maintain its contemporaneity,” he counseled. Earlier still, in 2001, David Carrier juried and made virtually the same assessment: “Relatively few videos and installations were submitted, and there was very little openly political art. Oddly little of the art submitted was rooted in this place or its history. On the whole,” he concluded, “the Pittsburgh art community is conservative.”

Obviously, it would be risky to generalize from one AAP Annual to “Pittsburgh art” at large; still, it’s worth pausing on Carrier’s point. We might assume that in a Pittsburgh context, “conservative” art would imply “regional” art, realistic representations of identifiable local landmarks or activities. But in the current Annual, the art has been scrubbed of regional identity, leaving formal qualities—form, color, scale, texture—to dominate. And it is precisely this absence of rootedness in place and history that, paradoxically, makes this Annual feel so conservative: The exhibition celebrates formalism and abstraction at a time when global contemporary art in general is moving in the opposite direction, towards realism, embodied experience, and historical and geographic specificity. This shift began in the 1990s, crystalized around documenta 11 (2002) and has intensified since, driving some of the most important work of the past decades, including Rachel Whiteread’s House (1993), the photo-journeys of Emily Jacir in Palestine (2002-03), and Jeff Wall’s quasi-documents of Vancouver’s exemplary banality. We live in a globalized age, but as Arjun Appadurai and others have shown, globality produces locality. Understanding how our localities intersect and complicate each other is urgent cultural work, and it’s an area where artists excel.

Attending to the specificity of place is important not only to connect local art more thoughtfully with art around the country and the world, but also to connect it with Pittsburgh itself. Our city is undergoing major changes—not all good, and some much worse for certain people. In this context, high formalism, however elegant, risks calcifying into indifference, or at minimum, of being received that way. All this isn’t to say that I am advocating for an Annual dominated by the likes of explicitly political artists such as Jonathan Horowitz. I’d settle for the gentler social critiques of David Hammons.

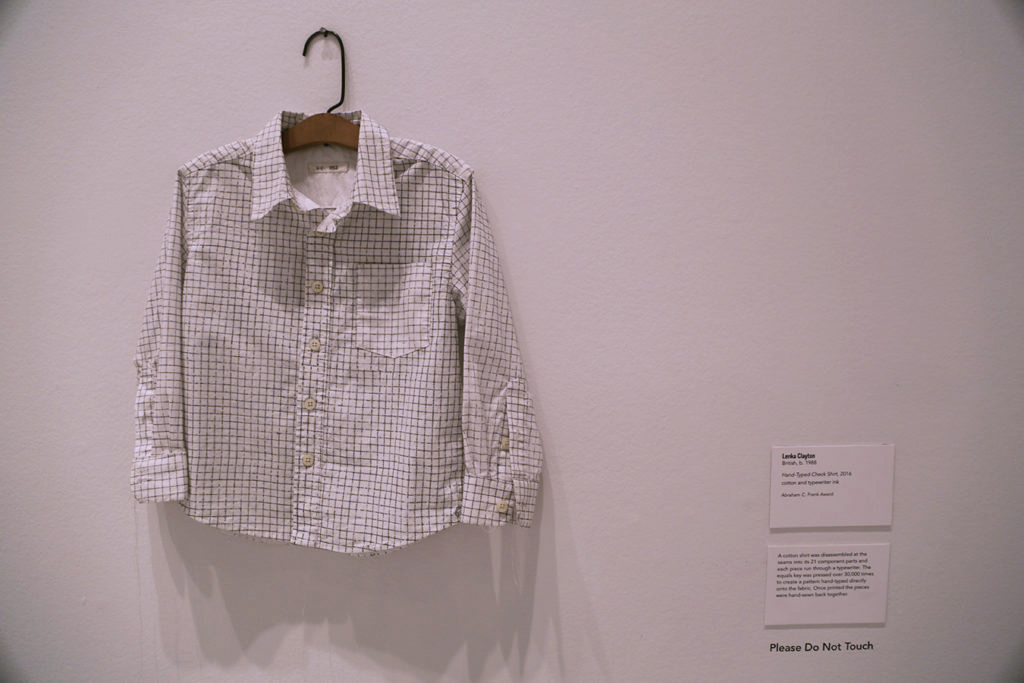

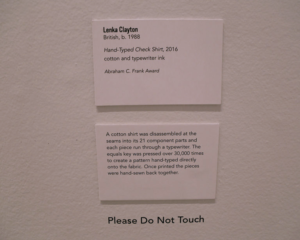

Otherwise, a little contextualizing information would go a long way in guiding visitors through this vast and eclectic exhibition. Apart from a prefatory statement from juror Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, no didactic panels are provided—with the notable exception of one for Lenka Clayton’s Hand-Typed Check Shirt. The wall card explains that the artist disassembled the child-sized shirt, passed it through a typewriter to create a checkered pattern with over 30,000 strokes of the “=” key, and sewed it back together. That minimal information grounded and enlarged my viewing experience, evoking repetition and ritual, the invisibility of labor in garment manufacturing, and the work of mothering.

Otherwise, a little contextualizing information would go a long way in guiding visitors through this vast and eclectic exhibition. Apart from a prefatory statement from juror Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, no didactic panels are provided—with the notable exception of one for Lenka Clayton’s Hand-Typed Check Shirt. The wall card explains that the artist disassembled the child-sized shirt, passed it through a typewriter to create a checkered pattern with over 30,000 strokes of the “=” key, and sewed it back together. That minimal information grounded and enlarged my viewing experience, evoking repetition and ritual, the invisibility of labor in garment manufacturing, and the work of mothering.

During the opening reception I caught up with Danny Bracken, an accomplished North Side artist who has used projectors and iPads to create intimate, multi-sensory installations and sculptures. He is not an AAP member. To him the organization always just seemed like an old club for Pittsburgh painters. But the high quality of the current exhibition impressed him sufficiently to make him consider joining. “I’ll try anything once,” he said. Of course, by the time the next Annual arrives, the iPad may be obsolete. But, as the saying goes, if at first you don’t succeed, try, try, try again.