I forgot the way a car defines you here, in Western Pennsylvania.

In New York, cars didn’t matter. Not to my group of friends, a pack of writers, teachers, and artists. We liked when someone had a car, and for that someone to be the kind of person who offers rides to Costco just when we needed three dozen rolls of paper towels. If a particular kind of wanderlust hit, we’d rent a car and drive upstate to pick apples on a farm, or out to Long Island to the beach, or to IKEA. For the most part, when we talked about cars, it concerned what a pain they were, how you had to pay outrageous sums to park them in the neighborhoods where we lived: $500! $1,000! Cars were status symbols, we knew, but also burdens, and we wanted to be free.

On trips home to visit family, on the rare occasion that cars would come up as a topic of discussion, everything would go blurry for me, as when people discuss wine. I couldn’t identify anyone’s cars anywhere. I would wander off through parking lots, completely unaware that I’d passed right by my brother’s car. “It’s taupe!” he once yelled across three lanes of a movie theatre lot. I shrugged, and the next time, I forgot again.

I grew up in Johnstown, where cars were both necessary and treasured. My parents gifted me their 1978 Plymouth Arrow when I was a senior in high school in 1991, and I drove it and relished the autonomy. The car looked as if the Dukes of Hazzard had painted the General Lee orange but stopped just before adding the Confederate flag. It wasn’t as nice as the little SUVs that a few of my classmates had, but it got the job done, allowing me to transport myself, my brother, a friend or two, and our cellos, to and from school and rehearsals. It died a noble death after my graduation, having completed its life’s mission of getting me where I needed to go for 18 months. I still miss it.

I started college in Ohio car-less, but my parents soon tired of the five-hour drive to fetch me for visits home, and a 1989 Chevy Corsica was procured for me. I hadn’t enjoyed having to rely on my dormmates for rides to the grocery store or the movies, so when I first parked that Chevy in the lot by my dorm, it felt like something wrong with the world had been righted. I could drive to Kroger’s, or Meijer’s, or even all the way to Gambier to see a high school friend now at Kenyon if I wanted. I could offer a cute boy a ride. The Chevy was nothing fancy, but who cared? I was 19 and had wheels. The world was in my grasp, again. So, yes: There was a time when I knew, and even cared about, cars.

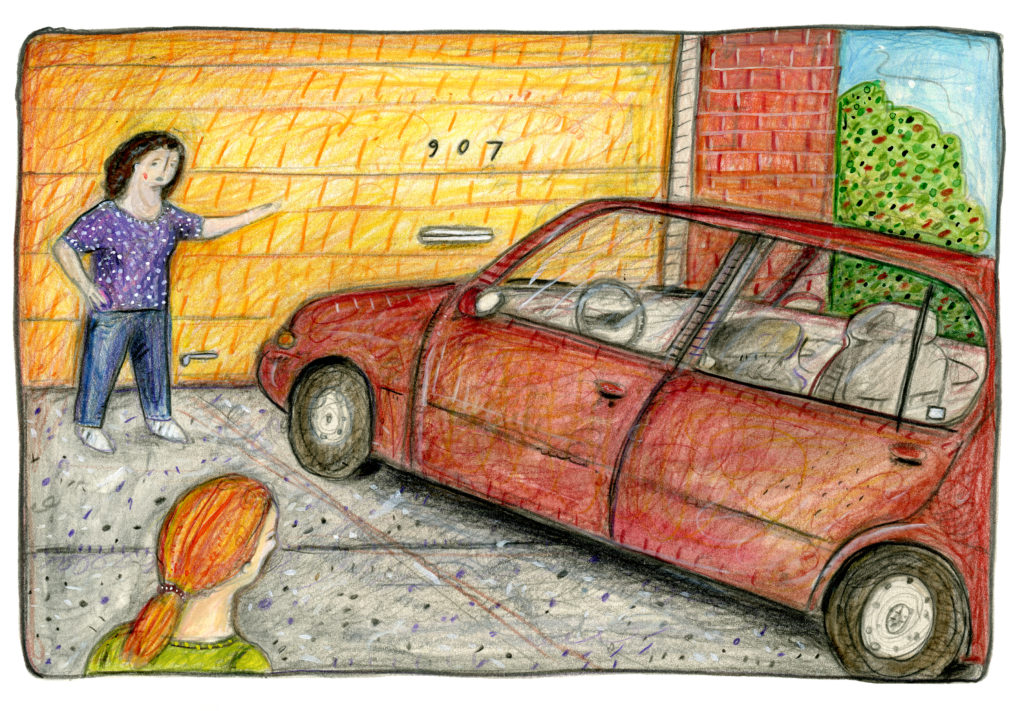

The idea of buying and owning a car seemed so perplexing in New York; all I could imagine was how much of a pain it would be to find parking in Park Slope. But when I moved to back to Western Pennsylvania to work on my MFA and teach at the University of Pittsburgh, to travel frequently between my apartment in the suburbs and Pitt’s campus, or to my hometown, two hours away—suddenly, a car was necessary. As they have so often done in the past, my parents came to my rescue, this time with their old 1997 Nissan Altima as a homecoming gift. The car had been intended for a charitable donation until I accepted Pitt’s offer. It might have been as baffled by this turn of events as I was: But when I moved back, it was waiting for me in my parents’ driveway, maroon, in exquisite condition, and about 15 years out of style.

“It’s a good car,” my mom says when I drive it to their house and she comes out to look it over. And it is. It had spent its entire life garage-pampered, until I came to take it off to the hinterlands and leave it outside all night, every night. It’s needed some repairs, sure, but it’s never failed to start up for me. Given its age and how poorly I treat it, it is remarkably persistent.

What it isn’t, though, is a status symbol. It offers neither the vintage cool of a 1978 Plymouth Arrow nor the sporty cool of my friend Gretel’s little 2013 Nissan Versa Note. When I moved back, I thought I had a pragmatic, city-dweller’s attitude about this. Good, I thought. I don’t want a stylish car. I want a car that, if it gets sideswiped from street parking, I won’t be sad, I’ll barely notice. I don’t want to worry about it being stolen, or keyed. I want a car that isn’t a target. And whenever I felt I missed the groovy Arrow, or envied the sparky little Versa Note, I told myself that the Altima was utilitarian, that it might fit the 19th century designer William Morris’s brilliant suggestion that we own nothing that we do not know to be useful or feel to be beautiful—the Altima is no great beauty, especially as rust starts to mosey up the sides of the car, but it is, however, endlessly useful. My Altima is a workhorse. It is completely unmemorable. I have walked past it in a parking lot.

During my first few months at home, the car proved to be a gift, but also a terror. I hadn’t driven much for more than a decade, and certainly never in a city. In New York, I’d always left the job to a friend. In Pittsburgh, behind the wheel, I was skittish. After offering rides, I’d subject guests to my Car Rules. In brief: Do not distract me. Also, all conversation is to be considered distracting.

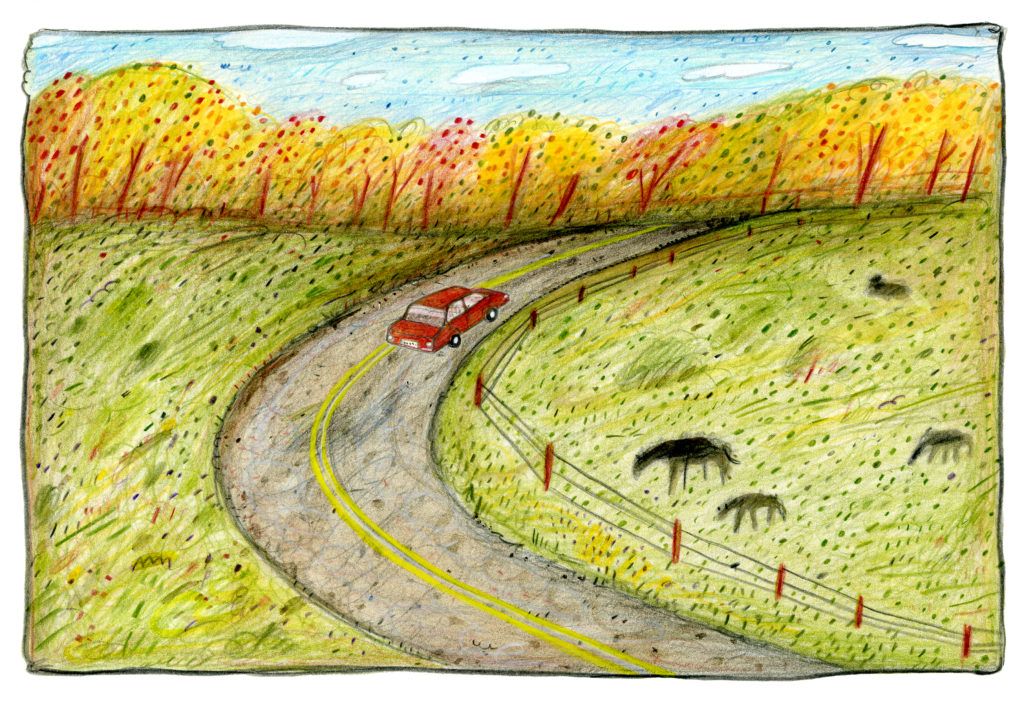

Nevertheless I was happy to be on the move—and I was so excited in my new, motoring life that for a long time I had been oblivious to the other drivers on the road hovering behind me, passing me too quickly, too close, exasperated, scowling at me as they zoomed past. I noticed from afar, watching strangers park their cars next to mine, that they didn’t seem to take much care whether they bumped or dinged my Altima. I could hardly complain—after all, isn’t this why I wanted a car like this? But still, it bugged me. She might not look like much, but she was mine. And I could drive where I wanted, when I wanted. I could pick up some things and deliver other things. I could meet someone for coffee spontaneously, without having to check the bus schedule. I could accept teaching artist work at a rural high school and arrive there on time. Go for an ice cream after class? Yes. Join a church not at all convenient to public transportation? Yes. Drive to Fallingwater to see it in the snow? Yes, carefully, yes.Though Western Pennsylvania is pretty, it remains almost entirely unsung. Our particular specialty here is the back road, nestling along low, sprawling mountains and swooping spectacularly through valleys. It’s the stuff of calendars and screen savers. Driving these roads is pure pleasure, and I had forgotten.

![]()

I went to register the Altima at the local AAA, and the woman behind the counter asked me for the make and model. When I told her, I was surprised by my own apologetic tone. “I drove my 1995 Nissan for ten years,” she assured me. “It’s a good car!” She gave me a sympathetic look and patted my hand. Wait, I thought as I got in the Altima to go home. Was she patronizing me? Was I embarrassed by my car? Should I be?

Growing up, we would roll our eyes when a car with a bad muffler pulled up next to us at a traffic light. It was always the old ones: A beat-up Ford truck. A collapsing Chevy Cavalier. Or a maroon, rusting Nissan Altima. One day I started up my car, and the transmission system roared to life. But very quickly it became clear to me—perhaps because the toddler next door put his hands over his ears and started crying when I backed out of our lot—that the muffler was shot. I was the one with the bad muffler.

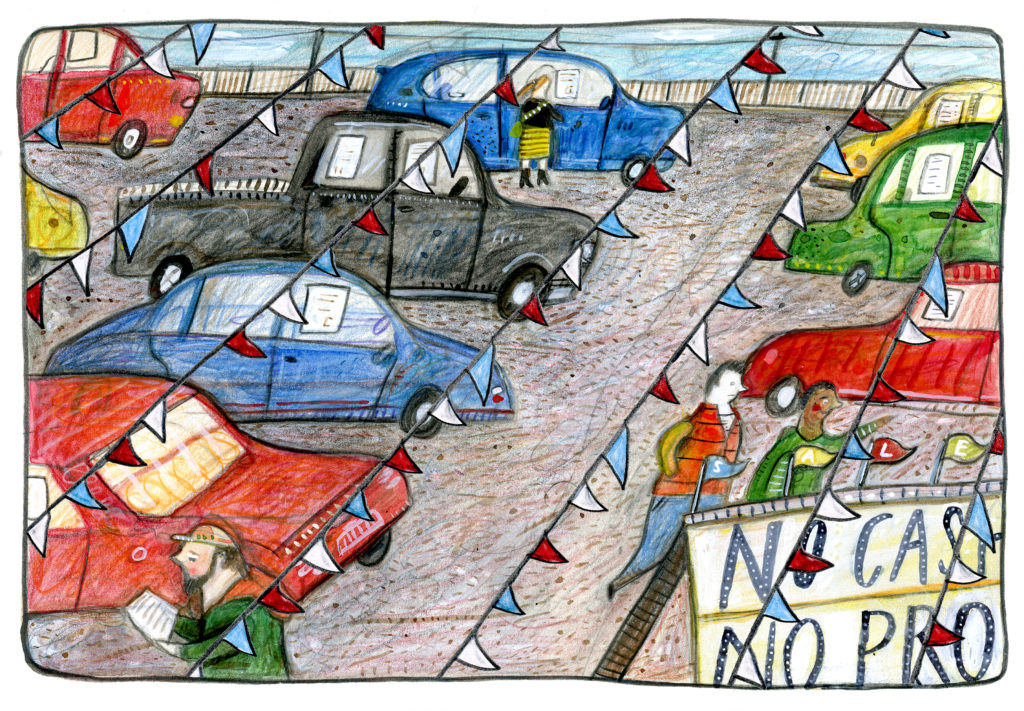

When I finally got the car to the garage, things looked dire, so while my parents and I awaited the mechanic’s ruling, we shopped the used car lot, where I was surprised to learn how many opinions about cars I had developed. No red, I said, too flashy. No gray either, too easy to miss in the fog. Electric would be nice. But something that could make it over the mountains.

I saw a blue SUV in a far row of the lot and wandered over to it, mostly to laugh at the idea of me driving such a thing. Reading the list of amenities, I was intrigued, and when I saw that the price was not outrageous—nor the sight of me standing next to it, interestingly enough—I began to entertain thoughts of casting off the Altima and taking on a new love. After all, the Altima was almost 20 years old. And it wasn’t even really mine. My family had driven it for 15 years and over 120,000 miles. Surely, a new-to-me car was justified?

As it turned out, the Nissan survived, and my brief flights of fantasy were dashed. It was much, much cheaper to fix the Nissan than to buy another car, especially a late-model SUV, so that’s what we would do. I didn’t have to be talked into the decision.

Later, I found myself shopping online for an SUV just like the one I’d seen at the lot. Maybe I could find a better price if I just put some muscle into looking. I found a couple of prospects, plugged in my income and potential payments, and realized, after a few attempts, the truth: I was already driving exactly the type of car I could afford. I know a time will come when I will replace the Altima, most likely because it has collapsed, hopefully in its sleep, never to start up again. Or it will age into a vintage classic. Maybe there will be a mania for late ‘90s four-door family cars. Rusty maroon will be the new black. I doubt it, but maybe.

I keep the key to the 1978 Plymouth Arrow on my keychain, twenty years after it went to the chop lot. When the Altima gives up the ghost, I plan to keep its key on my key ring too, to remember the time I took it out for a drive on one sunny Saturday, down a two-lane back road, where we entered a deep Pennsylvania wood, the trees glowing in the autumn light. It hadn’t mattered then what the car looked like, only what it had taken me to see.

Epilogue: In the summer of 2015, the Nissan finally died, and I inherited my mother’s Subaru Outback. I have the keys to both the Altima and the Arrow on my keychain.