Like other Rust Belt cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Pittsburgh was a destination for workers from Eastern European countries like Slovenia, Croatia, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland. By 1920, more than a third of those working in the steel and iron industry were foreign-born. And they arrived in Western Pennsylvania—and early each morning to the mills—with unique political traditions and values shaped by their experiences from home. For some, that meant Communist Party membership and political knowhow that emboldened an era of radicalized labor organizing. And in the 1920s and ‘30s, those cultural inroads allowed the Communist Party to enmesh themselves in a variety of local organizations to forge public alliances, recruit members, and build political power.

In May of 1931, 42,000 Pittsburgh-area coal miners laid down their tools in a “Strike Against Starvation” action led by the Trade Union Unity League, an industrial union umbrella organization under the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). At the time, it was the largest strike organized by a leftist political group in the United States. By the early 1940s, the Communist Party USA enjoyed an enrollment of 80,000, several thousand members of which could be found in Pittsburgh.

But even during the peak of its power in the 1930s and ’40s, the CPUSA remained more or less a party of two halves. The first of these two tiers included a combination of labor activists, public servants, white-collar workers, academics, artists, and intellectuals. Though the leadership recognized early on the importance of cities like Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Detroit—sending officers there to organize, recruit, raise money, and agitate—the majority of top-tier Communist talent remained concentrated in New York City and kept close contact with comrades in the Soviet Union.

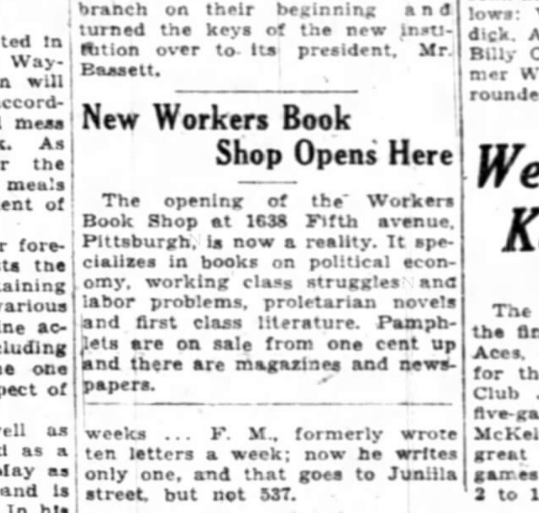

The second tier consisted of lower-ranking Communists and their sympathizers. These men and women were unionists and leftists of varying political persuasions more concerned with Main Street than Red Square. Pittsburgh’s Communist culture of the time reflected this tier, and places like the Workers Book Shop at 1638 Fifth Avenue in Uptown served as education hub, organizing venue, recruitment center, and a place to socialize.

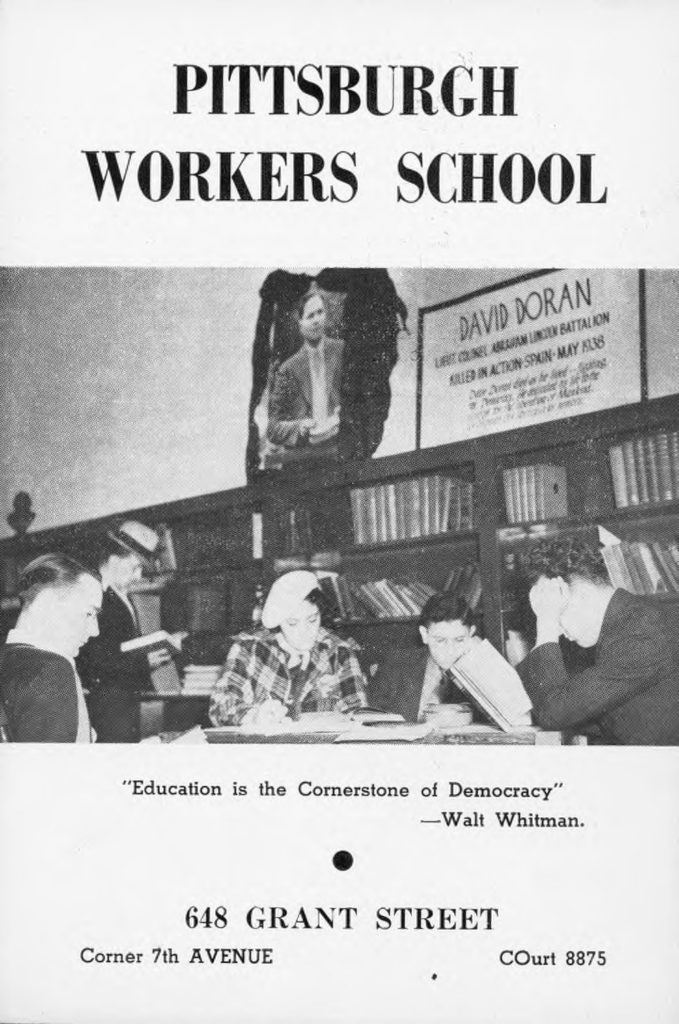

Like the Pittsburgh Workers School, its related academic training center for young comrades (located in a building on Grant Street at the corner of Seventh Avenue downtown today occupied by the hulking U.S. Steel Tower), the Workers Book Shop also served as bridge between the two unofficial tiers, maintaining the link between the international network reflecting the party’s revolutionary aims and what the Communist Party referred to as the United Front, a strategy of solidarity in which Party members allied themselves with a variety of struggles—including more localized fights for racial equality, workers’ rights, and peace. Through both the Workers School and the Workers Book Shop, Party members hoped to bring local sympathizers more completely into the fold—and to do so, they provided would-be allies with neatly curated information and educational opportunities.

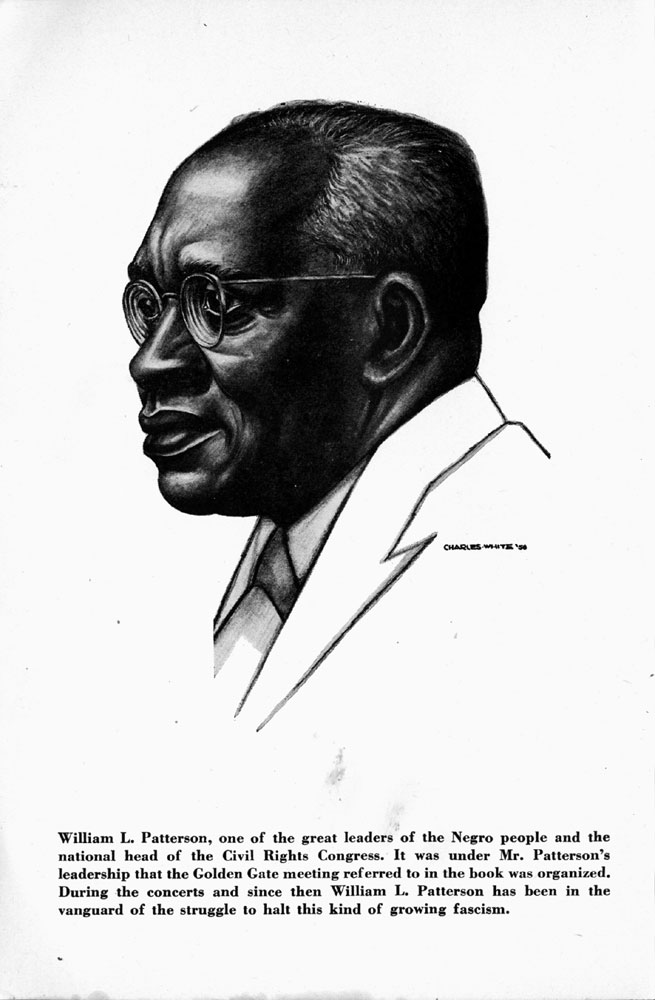

One such opportunity arrived in 1931 when Communist Party leader William L. Patterson came to Pittsburgh to direct and teach at the Workers School. A graduate of the Hastings College of Law of the University of California in San Francisco, Patterson dedicated his life to defending wrongly convicted African-Americans and labor activists, and his firm had aided in the defense of unjustly persecuted anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. While in Pittsburgh, Patterson and comrades were arrested for defying eviction orders by helping residents move back into the homes they had been kicked out of. Patterson, with his legal acumen, was able to successfully defend himself and his fellow activists from the charges of inciting a riot and resisting arrest. His stay in Pittsburgh was to be brief, however, as later that year he was called to serve as national secretary of the International Labor Defense during the trials of the Scottsboro Boys.

In a letter, Patterson described the role of the CPUSA’s educational fronts, writing:

“…Miners and steel workers were to learn the techniques of organizing, to study the history of the labor movement and to analyze our society and find out the whys behind the monstrous destruction being visited upon our people by the depression.”

Of course, the Workers Book Shop and Workers School served not just as hubs of political education, but social ones too. Alongside Party lectures, exhibits, and rallies, there were dances, theatrical performances, and at least one “River Outing and Weiner [sic] Roast.” Advertising an election night party on November 8, 1938, one flyer promised “Games, Dancing, The Magician, Eats, and Free Beer!”

![]()

Inside the modest Workers Book Shop, visitors could find copies of Marxist magazines like the Daily Worker, Sunday Worker and New Masses. More substantial volumes were also available—The Peril of Fascism: The Crisis of American Democracy by A. B. Magil and Henry Stevens, for example. One bookstore flyer announced the sale of Foundations of Leninism, by Stalin himself, a steal at just 10 cents.

The store also featured copies of the Communist Party’s various Pittsburgh shop papers, like the Westinghouse Worker. These hyper-local news outlets featured articles penned by workers in and around Pittsburgh. They helped keep workers apprised of the ongoing labor struggles at other plants and factories while encouraging solidarity within various trades and departments.

Patrons of the Workers Book Shop weren’t merely readers. They were proselytizers, too. The shop’s stocked shelves furnished party members with the literature necessary for recruitment. A flyer emblazoned with the words “Literature Builder” in big block letters extolled the virtues of Party recruitment via radical prose: “Every party member a literature seller, every literature seller an organizer for the party.”

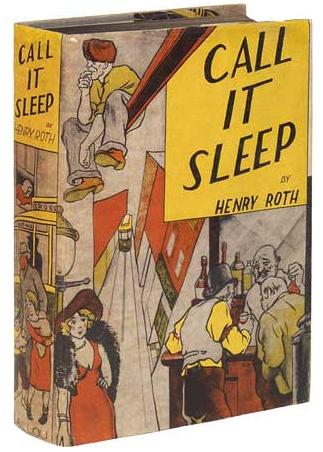

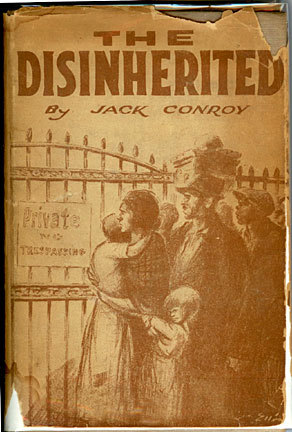

But dense leftist theory and praxis materials were counterbalanced with more digestible offerings. Communists needed pleasure reads too, after all, and at least a few of the shelves at the Workers Book Shop would have been reserved for the latest in “proletarian literature.”

With working class-conscious roots that go back hundreds of years, proletarian literature really picked up steam as a genre in the United States in the ’30s, propelled along the way by radical immigrants, opposition to the First World War, and the collapse of the world economy that triggered the Great Depression. Given its preference for art by the people, of the people, and for the people, the CPUSA had a hand in publishing a number of works of proletarian literature. But because there was no vast Communist nation state to finance or referee the genre’s evolution, proletarian literature in America was less uniform and more autonomous than elsewhere and perhaps, for that reason, executed with greater artistry. Still, there were commonalities that defined the genre. For a book to be considered proletarian literature, it needed to offer a portrait of working-class life, express sympathy to the political causes of the working class, and preferably be penned by someone with a working class background.

Published in 1933, Jack Conroy’s The Disinherited told the sad yet sympathetic story of a handful of mining families before and after the stock market’s Great Crash. The Studs Lonigan trilogy, by James T. Farrell, published in 1932, 1934, and 1935, relayed the fictionalized life of the eponymous working class hero. The trio of novels cast a disapproving eye on the ills of capitalism on the South Side of Chicago. For a slice of life from the Lower East Side’s Jewish immigrant ghetto, there was Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep, which recounted the hardships of a Galician Jewish immigrant family living in Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

It’s likely copies of more famous Depression-era novels, like the ones on high school English curricula—Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath or Sinclair’s The Jungle—were also passed around the Workers Book Shop.

Proletarian publications were by no means pulp—many of the aforementioned titles garnered awards and have since been critically acclaimed. A favorite among Communist leadership was the journalist-turned-novelist Theodore Dreiser. In 1930, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Years after his first commercial success An American Tragedy alluded to his left-leaning sympathies, Dreiser made his allegiance to Communism official: “Belief in the greatness and dignity of Man has been the guiding principle of my life and work,” Dreiser wrote to William Z. Foster, then general secretary of the CPUSA, in 1945. “The logic of my life and work leads me therefore to apply for membership in the Communist Party.”

Communists saw the entire spectrum of human expression as tools in the fight to smash capitalism. “Art for art’s sake” was a bourgeois concept, a motto for the rich. For Communists, art had an obvious purpose.

“The reactionaries looked with grave alarm upon this upsurge among the intellectuals and artists, upon whom they counted to drive their propaganda into the heads of the workers,” CPUSA general secretary Foster wrote. “But in the existing political situation, they were unable to stifle it.”

![]()

In the 1930s, Communists enjoyed the apex of their political success and public appeal, but through the ‘40s, as tensions strained between the briefly allied U.S. and the Soviet Union, Americans began to perceive of Communism as a grave threat.

It’s not clear when the CP shut down the Workers Book Shop on Fifth Avenue. By 1940, investigators with the Dies Committee (the House Committee on Un-American Activities, today most known for its post-war Hollywood blacklist proceedings, was chaired by Texas Congressman Martin Dies, Jr. at that time) raided the Communist headquarters at 305-7 Seventh Avenue. FBI agents raided the headquarters again in 1950, and Allegheny County jurist Michael Musmanno, who testified for the prosecution in the 1950 anti-Communist sedition case against Pittsburgh Communist Party leader Steve Nelson, described the headquarters as being “spilled over with books, pamphlets, circulars, leaflets, newspapers, and magazines. … The bookcases particularly abounded with biographies and treatises on Lenin, Stalin, Marx, Engels, and other Communist prophets.” His profile boosted by the anti-Communist crusade, Musmanno would go on to be elected to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania the following year.

It would be easy to pin the Communists’ decline on right-wing reactionaries. But in the lead-up to McCarthyism, anti-Communist labor bosses, faith leaders, progressive politicians—even workers themselves—were doing their best to weed out the radicals. The political muscle of labor’s left wing was no longer necessary, as many labor leaders had been co-opted by the industry, and gains made during the New Deal ensured a significant portion of the workforce earned a decent living during the postwar boom years—decent enough to neuter what had formerly been a pressing need for agitation. For liberal and labor leaders, Communists and their sympathizers were increasingly political liabilities, especially in Pennsylvania, where the Republican Party looked on the verge of relegating Democrats’ New Deal dominance to the history books.

During the late 1940s, as well as the ‘50s and ‘60s, anti-Communism was one of America’s most well-practiced professions. When other campaign strategies failed, the technique of “red-baiting” was always a reliable way to boost a politician’s popularity.

In the decades to come, Communists and their books had lost their potency: The capitalist order was stable. And after Reagan’s wrangling with the “Evil Empire,” America as hegemon, and the triumphant Third Way of neoliberal, corporate-friendly, centrist Democratic politicking, any lingering leftist sympathies appeared to have been thoroughly vanquished, absent from national politics.

![]()

The Communist Party’s influence in America was always overstated, even at its peak during the 1920s and ’30s, but the party’s growth and influence came at a time when our economic system seemed most vulnerable.

In the years since the Great Recession and financial crisis of 2007-8, cracks in the capitalist order have resurfaced. Inequality in America is doing its best Gilded Age impression, and economic recovery is happening too slowly for many Americans. What’s more, “socialism” is no longer a swear word: According to one recent poll, one-third of millennials view socialism favorably.

“Leftist groups today are organizing the way they have always organized, by distributing publications and having conversations to raise awareness and get new people engaged in the movement,” says Antonio Lodico, executive director of the Thomas Merton Center, a hub of leftist organizing in Pittsburgh. After Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and the election of Donald Trump, the Left is again resurgent, and in Pittsburgh, groups like the Democratic Socialists of America, Socialist Alternative, and the International Socialist Organization are growing. And for more than a decade, the Big Idea Bookstore in Bloomfield has provided radical literature and a space for anti-capitalist thought.

Throughout 2016, hundreds of thousands of Americans packed gymnasiums, stood out in the rain, and traveled long distances to hear a septuagenarian socialist speak on the Democratic primary campaign trail. For the first time in decades, a politician on the national stage expressed genuine disgust at the realities of American capitalism, and it gained traction. Braddock Mayor John Fetterman, an endorser of Sanders’s candidacy, spoke to a crowd in Market Square one chilly day in February of 2016, saying, “If you think inequality is just one issue, you don’t get it. Inequality is every issue—and how it permeates society.”