As part of The Glassblock’s sponsored partnership with the New Hazlett Theater, we are presenting a series of editorially-independent previews and reviews of the 2016-2017 Community Supported Art (CSA) Performance Series. Below is our review of Redemption: Sons by Drs. Tameka Cage Conley and Jason Mendez, a collaborative response from editor Adam Shuck, arts and culture editor David Bernabo, and guest panelists Yona Harvey and Felicia Lane Savage. Read their bios below. And read our preview of the performance here.

Yona Harvey is the author of the poetry collection Hemming the Water, winner of the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. She recently co-wrote with Ta-Nehisi Coates “The People for the People” in Marvel’s World of Wakanda, a companion series to Coates’s Black Panther. She teaches in the University of Pittsburgh Writing Program.

Yona Harvey is the author of the poetry collection Hemming the Water, winner of the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. She recently co-wrote with Ta-Nehisi Coates “The People for the People” in Marvel’s World of Wakanda, a companion series to Coates’s Black Panther. She teaches in the University of Pittsburgh Writing Program.

Felicia Lane Savage is a registered yoga instructor with a background in natural sciences and education. For nearly twenty years she has owned and operated YogaRoots On Location, which teaches whole body health and wellness while incorporating culturally relevant music, developmentally appropriate movement, holistic nutrition education, and contemplative care practices that include self-awareness and self-care techniques.

Felicia Lane Savage is a registered yoga instructor with a background in natural sciences and education. For nearly twenty years she has owned and operated YogaRoots On Location, which teaches whole body health and wellness while incorporating culturally relevant music, developmentally appropriate movement, holistic nutrition education, and contemplative care practices that include self-awareness and self-care techniques.

![]()

In the summer of 2015, Dr. Tameka Cage Conley and Dr. Jason Mendez kindled a friendship around a late night campfire deep in Ohio Amish Country. As part of their participation in Penn Avenue Creative, a 12-week initiative from the Kelly Strayhorn Theater aimed at fostering leadership in Pittsburgh’s creative arts community, Conley, who was a workshop facilitator, and Mendez, who was a program fellow, took part in a three-day retreat that ended up changing the course of both of their lives—and which brought them to the New Hazlett Theater, where on December 8th, 2016 they performed their Redemption: Sons to a packed house.

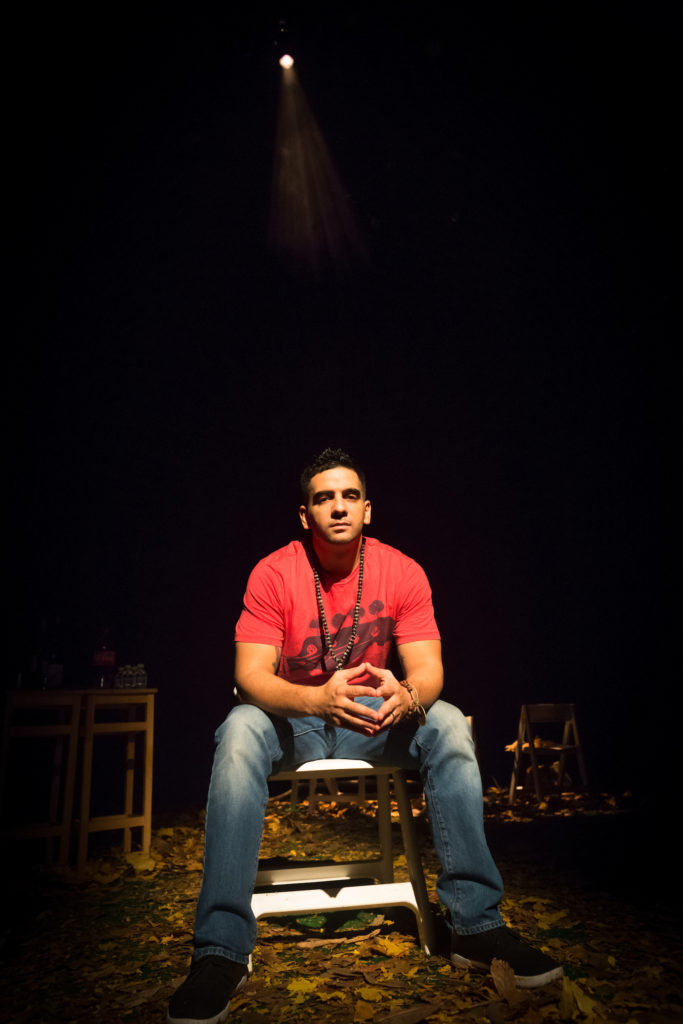

Redemption: Sons, which weaves personal stories from childhood to present, touching on memory, loss, pain, and joy, is strikingly intimate and simultaneously rich and spare. “So everyone’s just gone to bed?” Conley asks Mendez to open the performance, as she pours herself a drink and approaches him as he’s writing fireside, and we feel transported to the strange hush that’s left after the excitement of a crowd of people has dissipated. Crunching leaves barefoot, with a faint whistle of birds in the distance, Redemption: Sons places us in those woods with Conley and Mendez, around that small fire that illuminates a soft space in the larger expanse of darkness. This simple, direct staging communicates an intimacy, signaling to the audience a cue to lean in. Listen.

Throughout their conversation, first a bit stilted and then increasingly warmer as they get to know each other, Conley and Mendez exchange bits of influential writing and details about their personal lives—Conley recites Lucille Clifton’s succinct poem won’t you celebrate with me; Mendez tells of the birth of his son Cairen—and, little by little, Conley and Mendez realize the similarities they share in both.

For Conley, an experience during a levee breach in her hometown of Shreveport, Louisiana served as reminder of the chilling realities of inequity. Rescued from her flooded lowland neighborhood and brought to higher ground, she recalls realizing, “There was sanctuary right up the street?” As a Black woman of dark complexion, she struggled with issues of colorism. “My black is beautiful,” Conley tells Mendez, “and my black is an open wound. … I love myself hard. But trauma is hard to shake loose.”

For Conley, an experience during a levee breach in her hometown of Shreveport, Louisiana served as reminder of the chilling realities of inequity. Rescued from her flooded lowland neighborhood and brought to higher ground, she recalls realizing, “There was sanctuary right up the street?” As a Black woman of dark complexion, she struggled with issues of colorism. “My black is beautiful,” Conley tells Mendez, “and my black is an open wound. … I love myself hard. But trauma is hard to shake loose.”

Mendez, a “Bronx Boricua” whose home was both Hunts Point and “La Isla Del Encanto,” offers a take of his own identity shaped from the words of poet Lemon Andersen: “I’m a suspicious mulatto, which means I’m too black to be white and too white to be doing it right.”

But as they exchange bits of poetry and prose, song texts and actual audio, perhaps no connection becomes more salient than that of parenthood. Raising children in Pittsburgh—children who are not white within a majority white city, and within the structures of white supremacy—is an experience they share. Conley tells of an incident in which, on a field trip with her toddler Maze, the young boy, tired and fussy, grabbed the shirt of another woman, the white mother of another young child. Instinctively, Conley tells us, the woman abruptly pushed his hand away rather than engaging with her and her partner, Maze’s father. It was because he was African-American, Conley says. Mendez shares an experience in which his son, said to be misbehaving, was unjustly chastised and removed from class—put into an “alternative space” with “alternative worksheet” assignments, Mendez points out—while his fellow white classmates received no such discipline. Because Mendez’s son is not white, he must travel through the world differently, held to different standards, and Mendez laments in a painful, verbal pacing, “I don’t wanna tell him that. I’m gonna have to tell him that. I don’t wanna tell him that. I’m gonna have to tell him that.”

Conley expresses her pain at the death of Tamir Rice, the 12-year-old boy who was shot dead by police officers while he was playing in a Cleveland park two years ago. A grand jury declined to indict the officers. In February of this year, at least a half dozen Pittsburgh streets were closed, Port Authority buses rerouted, while a funeral procession wound its way from the East Busway to a memorial on the North Shore—all for a police dog, a K-9 who was killed in an incident in which officers had shot and killed a man named Bruce Kelley Jr. Conley shares the experience of stifling the raw emotion she wished she could have let out while riding the bus that day. “The scream became an ache,” Conley says. “Why do we still live in America, Jay?” she asks Mendez. And then, at a point of crescendo, Conley pierces the dark theater with a visceral, bone-chilling scream. In it, she allows us to physically feel her ache.

The name of Mendez’s son, Cairen, shares a striking resemblance to a daughter whom Conley lost in a traumatic miscarriage. In frank detail, Conley shares with Mendez how she lost a liter of blood when an ectopic pregnancy turned “a passage for life [into] a passage for death.” Years later, she and her husband celebrated the birth of their son Maze.

The jubilation of raising a child is so great, so fundamental, that Mendez describes it in human senses, remarking how his father would walk the blocks around their South Bronx home, grandson in his arms, bowing his head to sniff the top of the infant’s head. Smell, he says, “brings us closer than any embrace.” But in a tragic twist, the date of his son’s birthday ends up becoming the date of his father’s death.

The jubilation of raising a child is so great, so fundamental, that Mendez describes it in human senses, remarking how his father would walk the blocks around their South Bronx home, grandson in his arms, bowing his head to sniff the top of the infant’s head. Smell, he says, “brings us closer than any embrace.” But in a tragic twist, the date of his son’s birthday ends up becoming the date of his father’s death.

This discordant duality, in which the site of trauma is also the setting for joy, is perhaps the performance’s strongest theme. “This is a thing I’ve been trying to put into words forever,” Mendez tells Conley and the audience. In Redemption: Sons, he and Conley have succeeded.

Conley’s story of “the place in her body where she’s expecting life but [which] was a site for death,” reviewer Yona Harvey shared in our conversation following the performance, “that was really haunting to me. That’s really stayed with me.” Fellow reviewer Felicia Lane Savage agreed. “That space, that’s where I live my life too.”

Harvey expressed a personal discomfort, a squeamishness at the performance’s naked honesty, one which plumbed issues of race, identity, and fear that she related to on a personal level. But, she offered, “I think that’s good.” In the practice of yoga, Savage explained to us, “we take people to their edge and play with that edge.” It’s uncomfortable, of course, “but that’s where we learn.” And though “it’s a very vulnerable space to be in, I think that’s what’s revolutionary about it. And I could feel that in [in the audience] too. I felt people were uncomfortable.”

Punctuating the performance were several brief pauses. The lights went down, and for some attendees, Harvey and Savage included, they were critical moments. “It was almost like a cleansing ritual,” Savage shared, a time to sit with the intensity of what had just preceded, and “then I can get myself ready for the next [segment].”

In conversation with them for our preview of their performance, Conley and Mendez shared their intent behind the creation and staging of Redemption: Sons as a “duologue,” a theatrical performance—thanks to the dramaturgic advising of Edwin Lee Gibson and Christiane Leach Dolores—of very real experiences. Though its framing places Conley and Mendez on a set, reciting lines, in front of an audience, Redemption: Sons is no “play,” and Conley and Mendez, though they are performing, are not “acting.” This is how it really was, they communicate to us—but in doing so, they are not just going through the motions of a lived experience for the sake of historicity, but rather in order to bring the audience along with them into their growing friendship. Through this deft framework, relying upon and then adjusting our implicit relationships to the experience of being in a theater, the writer/academic duo of Conley and Mendez are able to draw us in, to bring us to a place where their messages can hit harder than at any bookstore reading or university hall lecture. In the dark, gazing upon them on stage, we are absorbed.

Because of its distinct approach to the stage, the performance’s small technical issues concerning lighting (the subjects at times walked into shadow, as lighting design didn’t fit their movements, or vice versa) and sound quality (the mic volume could have been a bit louder, with a boosted high-end) were noticeable but then almost immediately forgiven.

In their share-and-respond style, Conley and Mendez have recreated on stage the rhythms of the ongoing email correspondence that has built their friendship. Stepping up to take the spotlight, at times literally, their sharply focused mini-monologues are presented in harmony, and one that’s tinged with the duality of trauma and joy. Impassioned, plaintive, and confessional, Redemption: Sons relays its stark, deeply personal stories of loss and healing in a sharply effective manner, and, with grace, Drs. Tameka Cage Conley and Jason Mendez have invited the audience in to listen.

![]()

The New Hazlett Theater’s 2016-17 CSA Series continues with the February 16, 2017 performance of A Love Supreme by Anqwenique Wingfield and Julie Mallis. Look out for our preview in the coming weeks. And sign up to become a member of the CSA here.