Light, cracked clay, foam, action-triggered sound, reflective surfaces, skewed video—multi-disciplinary artist and print shop director Brandon Boan works in transformation, experimenting with a broad range of materials and often obscuring their original identity in the process. For The Glassblock, artist Celeste Neuhaus visited Waxing & Waiting, an exhibit of Boan’s latest work at 707 Penn Gallery, and reflects on his philosophy of art, observation and mediation, alchemy, and other topics.

![]()

Brandon Boan’s work isn’t easy, and he doesn’t want it to be—that isn’t the point. There is no point, in fact, at least not in the sense of one singular conclusion. Instead, there are “endless conclusions” at 707 Penn Gallery, where Waxing & Waiting, an exhibit of his latest sculptural work, is on view.

It may seem almost irresponsibly open-ended—or bullshit—but my experience of Waxing & Waiting was as a thoroughly orchestrated and deeply relevant proposition.

I enter the gallery and read the title of the show on the wall.

Waxing & Waiting

(On Plastisticity [sic] and Human Synthetics)

It’s dimly lit. I scan the space.

A large, black, wall-mounted triptych displays a set of imprints of some kind of organic substance. Repetition functions here like Warhol’s soup cans. The insistence elevates the inconsequential until it becomes iconic.

A large, black, wall-mounted triptych displays a set of imprints of some kind of organic substance. Repetition functions here like Warhol’s soup cans. The insistence elevates the inconsequential until it becomes iconic.

Historically, triptychs contain depictions of holy icons. But from the wall piece to a series of objects arrayed in groups of three across several tables, Boan’s sculptures have less in common with the Holy Family and more with the grotesque demonic figures of Hieronymous Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. These objects flirt with profanity.

They are figurative in the sense that they refer back to the body in several ways. In one grouping of tabletop objects, one can’t help but see a dick and balls. Other objects, spherically compact, formed by clenching and pinching, and with the apparent texture of wet clay, resemble excrement. Traces of their matte residue muddy the sheen of the black slab they sit on. These forms act as evidence of their own creation, like action painting meets three-dimensional finger painting.

They are figurative in the sense that they refer back to the body in several ways. In one grouping of tabletop objects, one can’t help but see a dick and balls. Other objects, spherically compact, formed by clenching and pinching, and with the apparent texture of wet clay, resemble excrement. Traces of their matte residue muddy the sheen of the black slab they sit on. These forms act as evidence of their own creation, like action painting meets three-dimensional finger painting.

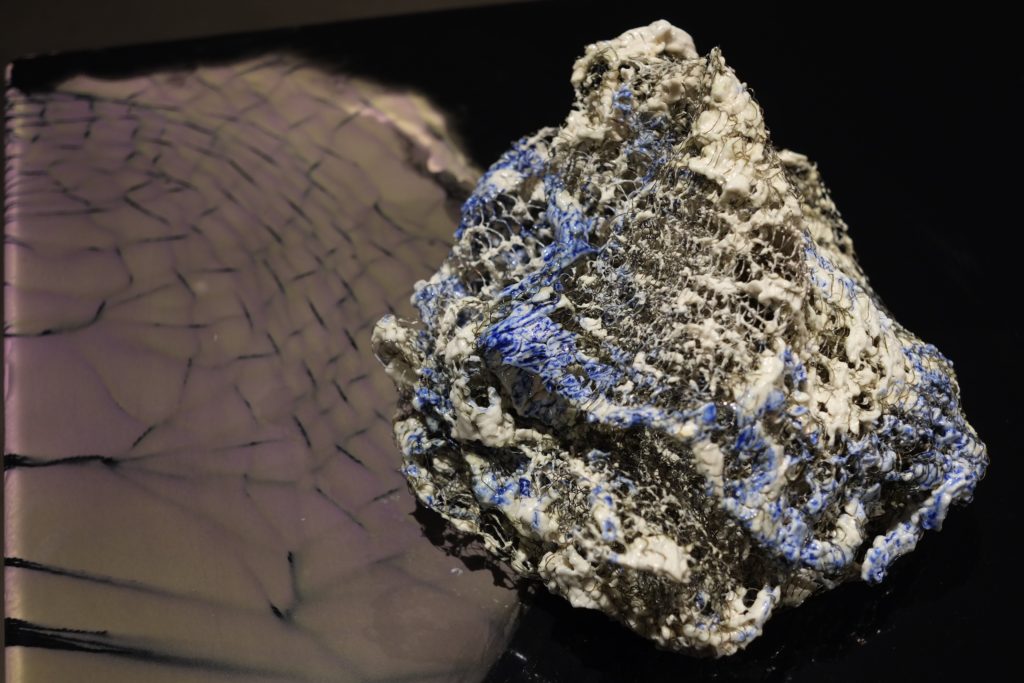

The next grouping of three objects is a trio of blobs and globular forms that combine materials both indiscernible and recognizable. Their composition seems to lack intention, in the sense of a preconceived plan, and I wonder how much the creation of their form has been determined by happenstance. One object looks like it is mainly composed of wire mesh and covered in a glaze that resembles snot, pus, or semen.

I am intrigued. I want to know what these objects are made of and what processes are involved, but there are no accompanying lists of materials or mediums—in fact, there are no titles at all.

The surface of a third tabletop retains the effects of a viscous liquid that has spread across the surface, frozen, like the pooling of pigment in a Helen Frankenthaler color field painting, but with a more physical dimensionality. The last table top has etched traces of the rotational movement of some kind of tool, again a document of a physical process.

Suddenly, through the gallery’s dim lighting, it hits me that these tables are laboratory tables, and I flash back to high school chemistry and having to clean that black slab surface after a messy experiment, and to high school biology and dissecting parasitic worms. Ascariasis is an infection caused by a roundworm in pigs’ intestines, I think, this factoid emerging like a freshly unlocked memory.

It feels like a subtle epiphany. I can now see these objects as being presented for study, like a grouping of specimens. I think of the steps of the scientific method: observation, hypothesis, experimentation, conclusion. With my new lens in place, and having drawn some conclusions of my own, I checked in with artist Brandon Boan.

Boan’s work isn’t a critique of the scientific method, he tells me, but instead, “It’s an effort to pry open the playing field to get to something else.”

He sees his sculptures like rocks or other curated specimens, housed in an environment like The Hall of Gems and Minerals at the Carnegie Museum, and by referencing its formal exhibition design, he is prompting the viewer to accept what he’s presented more objectively. Like a chef arranges food on a plate or an usher hands out 3D glasses at a movie theater, Boan’s approach relies on crafting an environment or relationship so that the sensory experiences are the focus.

Boan also works with a performance group called 181 that sets up stations they call “observational practices.” His other work often references lenses or other objects that you look through in order to bring awareness to the mechanism of viewing and therefore emphasize observation itself.

There is much content to be discovered in Brandon’s material choices. Outside of the work in this show, his practice involves “pulverizing cat litter and mixing it with toothpaste,” he explained, “to make a sort of colloidal silicon because the sodium bicarbonate (or baking soda) in toothpaste turns into flux and glaze when fired.” Fun fact: His sister is a chemist.

When asked why his sculptures lack any identification of materials, he says he doesn’t think it’s important, and this is apparent in both in his work and his orchestrated mode of display; he wants to give people the opportunity to just observe, period, and not be hindered by the preconceived notion of what it is they’re looking at. Driven by the question, “What is our mediated sensorium and what is our departure from that?”, Boan argues that the information that technology makes readily available “is a tool we use to make us feel like we understand, but instead, it distances us. It gives people a conclusion, but it doesn’t get them to do what I want them to do—I want them to make that [intake of information] a slower process.”

It’s a pretty radical stance to take. In Boan’s philosophy, the fetishism of industrialization’s technology and speed, as embraced by the Italian Futurists, has met its Information Age rebuttal.

![]()

In her published collection of lectures Alchemy, Jungian psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz says because they were working without the limitations of an existing scientific model, the alchemists were able to conduct research that would otherwise have been disqualified outright—even if it contained valuable information. Waxing & Waiting presents us with another model, one in which Boan primes us to notice, because of our cultural preference for the immediate, that which we would otherwise unconsciously disregard.

Many of the materials in Boan’s work, like polymers, resins, and fluxes, were formed through the processes of chemical reactions. Boan sees himself like a scientist working in a lab in his basement, making independent discoveries.

When clay is fired, its chemical makeup is entirely changed. It becomes an entirely new material. (Transmutation does happen. Alchemists were not fools, they were pioneers.) Boan’s experiments are a small-scale way of speeding up what naturally happens in the center of the Earth in geological time. It is the human imposition of speed onto a natural process, which inspires the “synthetics” of the show’s title. Think fake diamonds. Of the work in this show, Boan says, “Every single piece is a direct reference to immediacy of human existence.” The evidence of immediacy in the work (the happenstance, the frozen moment) is echoed by this phenomenon of compressed time.

Our lives are often filled with a whirl of images and blurbs. We consume information at an accelerated pace. We want what we want when we want it, and we get it immediately. But what do we lose when we choose convenience over allowing time for making discoveries through experiential contemplation and reflection?

By offering a blank, a pause, a space yet to be filled, Boan advocates for careful and qualitative observation of the empirical data that our senses are continuously collecting, and for taking the time to examine and question the methods by which we extract and generate meaning.

Waxing & Waiting risks displeasing you in order to show you something, and it rewards with the rare opportunity to focus.

Waxing & Waiting is on view at 707 Penn Gallery through November 6, 2016. More of his work is also currently on view in the group show Checks & Balances, curated by Murray Horne, at SPACE through November 27, 2016.