On a warm fall evening, I walk up the stairs of the Romanesque, castle-like Braddock Carnegie Library. The savory aroma of fried foods fills my senses and warm sunlight pours through the windows onto a gathering of people in the library lobby. From the back of the room, the blazing sound of hip-hop and R&B emerges from a boombox, and D.S. Kinsel, creative entrepreneur and co-founder of Garfield arts and performance hub BOOM Concepts, steps forward to welcome me to his show A Black Man Made This Art. One of three coordinated shows revolving around themes of agitation and Americana, this particular exhibit explores the loaded concepts of patriotism, consumerism, and oppressive—or otherwise culturally offensive—language.

Most of Kinsel’s work is on the first floor on the library, adorning the wall above the book displays and sandwiched between flyers for An Answered Prayer LLC, the Braddock Salvation Army Worship and Community Center, and others. In one piece, two feet—one in a pink Nike sneaker and the other in lime green—have been stamped several times, giving the effect of movement. In another, an American flag’s stripes are adorned with black Nike swooshes, and green dollar signs cover the field of stars. To the left of the flag is a series of neon painted Nike swooshes and a mostly black and yellow print of Kinsel dribbling a basketball.

Most of Kinsel’s work is on the first floor on the library, adorning the wall above the book displays and sandwiched between flyers for An Answered Prayer LLC, the Braddock Salvation Army Worship and Community Center, and others. In one piece, two feet—one in a pink Nike sneaker and the other in lime green—have been stamped several times, giving the effect of movement. In another, an American flag’s stripes are adorned with black Nike swooshes, and green dollar signs cover the field of stars. To the left of the flag is a series of neon painted Nike swooshes and a mostly black and yellow print of Kinsel dribbling a basketball.

It’s basketball that is America’s pastime, Kinsel argues, rather than baseball, and his latest work’s focus on the sport was inspired in large part by a recent ten-day residency at the Sedona Summer Colony in Arizona. There, Kinsel found a “retreat from the hustle and bustle of daily life,” he says, but also an opportunity to “expand [his] Blackness.”

“A lot of times I don’t feel like I have the words, [but] I’m able to express them digitally,” Kinsel says. “What you’re seeing is that expression of pain.”

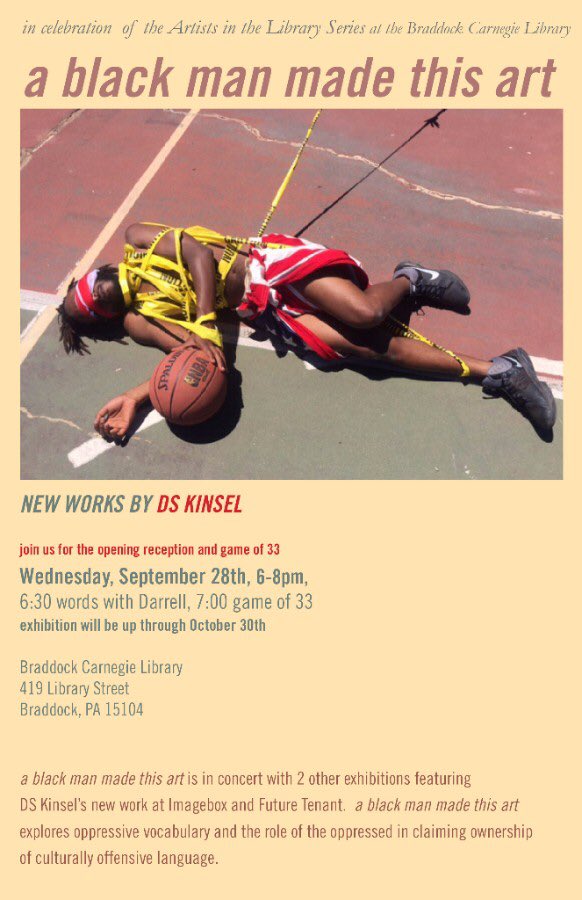

Indeed, expressions of suffering seep out of the work. In a series of self-portrait photographs of a basketball court during a sunny, and presumably sweltering, day, the American flag envelopes Kinsel, who is blindfolded. Yellow police caution tape scaffolds his torso.

“I just want to raise awareness about things happening,” Kinsel tells me. “It’s not one murder. It’s not one instance. It’s not one encounter with police. I think this is a conversation about the extended condition. We oftentimes have to turn to sports as an escape. And I think I’m just maturing with my work where I feel comfortable using myself and using basketball—because it’s a little more personal.”

The most striking piece in Kinsel’s Braddock show, though, is a large American flag displayed on a glass-topped wooden table in a reading room. “I pledge allegiance to the cash of the United States of America,” Kinsel has hand-painted in white block letters, with touches of smudged neon green, a style reminiscent of Kinsel’s street art. “It resonates with everybody no matter how you look at the situation,” Braddock resident Terrance Murtaza said as he walks through the exhibit. “It relates in a positive way no matter what color you are.”

During a twenty-minute artist talk at the Braddock Carnegie Library opening, Kinsel shares with the audience the recent opportunities that had provided him the platform to create his three related shows, but he also expresses his frustration with the lack of coverage and art criticism for Black artists in Pittsburgh, a point that he and other Pittsburgh artists have voiced again and again. “I thought, why not have the shows be related,” he shares. “Maybe somebody will write about [them] if I do three shows instead of one a month.”

Following a brief Q&A in which Kinsel fields questions related to his Sedona residency, his photography, and the inspiration behind his work, attendees are invited to enjoy more food (including cold treats from Dream Cream Ice Cream) and then join the artist in playing a game of hoops on the basketball court on the library’s second floor.

Kinsel’s opening at the Braddock Carnegie Library allowed each person to move beyond being a passive viewer of art to become an engaged voice in the conversation—a crucial element in A Black Man Made This Art, which confronts viewers with uncomfortable elements of American society. What you decide to do with that discomfort, however, is up to you.

A Black Man Made This Art is on view at Future Tenant, ImageBox, and the Braddock Carnegie Library through October 23, 2016.