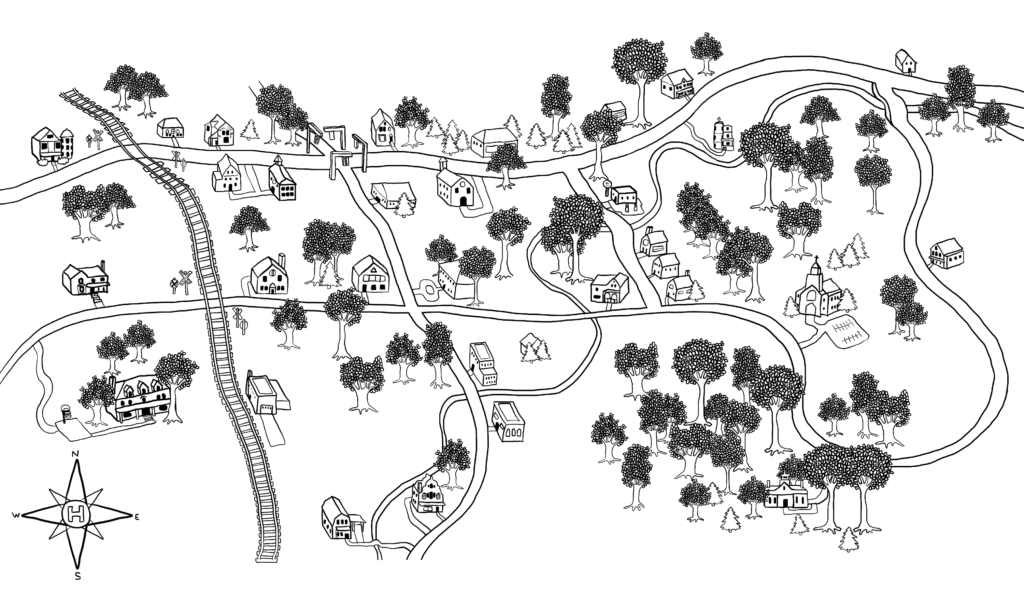

“The more enlightened houses are, the more their walls ooze ghosts,” Italo Calvino offered in a 1967 lecture. In their 2015 chapbook hamnett house histories, writer Marlee Gallagher and illustrator Greg Sciulli spun the spirit of the houses in their neighborhood—some long-vacant and on the brink of demolition, others still animated—into a collection of prose poetry. In a two-part series for The Glassblock, Gallagher and Sciulli share their sketches. See part two here.

![]()

ella winter boyd

Abe could blow her kisses when his hands weren’t strapped to the hospital bed splayed out in the middle of the living room. Sometimes his gown would get wrapped up on his legs so she could see his stick and poke tattoo, a monster, dark and sour green, she thought, like her sister’s sunken cheeks.

Before his accident, his family didn’t know that they took acid in the summer and chased waterfowls. It was her birthday. There were other ways she had planned to spend it—surrounded by a birthday cake and her mother’s gigantic heart. But they lay down in the backyard instead and watched the clouds pulse and drone all afternoon.

In the end, they watched nature shows, spread out in the space Abe’s bed now occupies, and she felt sad for what they’d done.

before the tiny house

concerning poppy mccrae

The house had many rooms despite its size. Everyone always entered from the rear door. So, though traditionally it should have been a foyer, the first room guests entered was a kitchen with linen drapes and red shelves.

A wood burning stove and restored barn wood floor led to a hall that separated the small stairwell from a large living room, full of antiques and oriental rugs and lambskin. A long, thin bathroom stretched out beyond the worn fringe of two overlapping rugs. At the end of it, below a single window, was the clawfoot tub where she’d save her bath water.

Beyond that, a dining room, entryway, first floor bedroom, and other nooks weaved through the space. A patio with lanterns adorned the outside. During the summer months, she slept alone and sweating in the angular upstairs with painted wide-plank floors. The upstairs contained two bedrooms, connected by a door, an unfinished space full of steamer trunks, and a bathroom with a tiny tub like a 19th century liver bath. Her room was full of John Gallagher’s old books and chests, his typewriter, and his regal cologne bottles and lace doilies.

When she knew it was the last time, she took into account every detail of the house: the holes in the window screen, fringe on the placemats, precise movements needed to open or close every door and window dpending on the season, dry rot on a woven nylon hammock that swung over crisp grass, bagpipes she heard across the wildflower sea on a C.

And for no particular reason, she remembered it longingly. No matter where she was or who she was with in life, she thought of the house. How it once sat off a side street between two much larger, grander houses, how behind it was the ancient shed forever tilted toward collapse yet never falling, and how the ground, covered, uncovered, and covered again by layers of broad plane tree leaves, felt underfoot. It wasn’t like that anywhere else.

the moving house

concerning aubrey “mamie” harrison

A hundred years ago the house was moved, and everyone thought that was so special. How rare. How interesting. How fantastic people were back then. But anymore, she didn’t care.

She’d sit in her bedroom and think, “Sometimes it would be nice to have a computer. Or a gun.”

And other times, she could still hear his voice, calling up the stairs, “Please, please, please. We can still have a good life.”

cora sperling

Because she couldn’t figure out what was wrong, she started forcing herself to experience more, hoping to find meaning or love or purpose or god. Whatever. It didn’t matter what the what was as long as it made her feel like she was something.

She’d see movies; indie ones, long irrelevant old time-y ones, and blockbusters, too. She would go shopping but, unsatisfied with the make and material of everything, she’d leave every store intact. She’d go to museums and try to find god there in the post-modern sculptures, in the interactive play on light and shadow pieces, or the annex turned cave made out of books and junk (a cliché on contemporary American wasteful behavior). Or whatever.

Sometimes she would see a painting or catch the last 15 minutes of a hit show, and think, yes, yes! This is it. The what, the thing. But the what would last only a few minutes before she’d delve back into the meaninglessness that kept her waking up again and again.

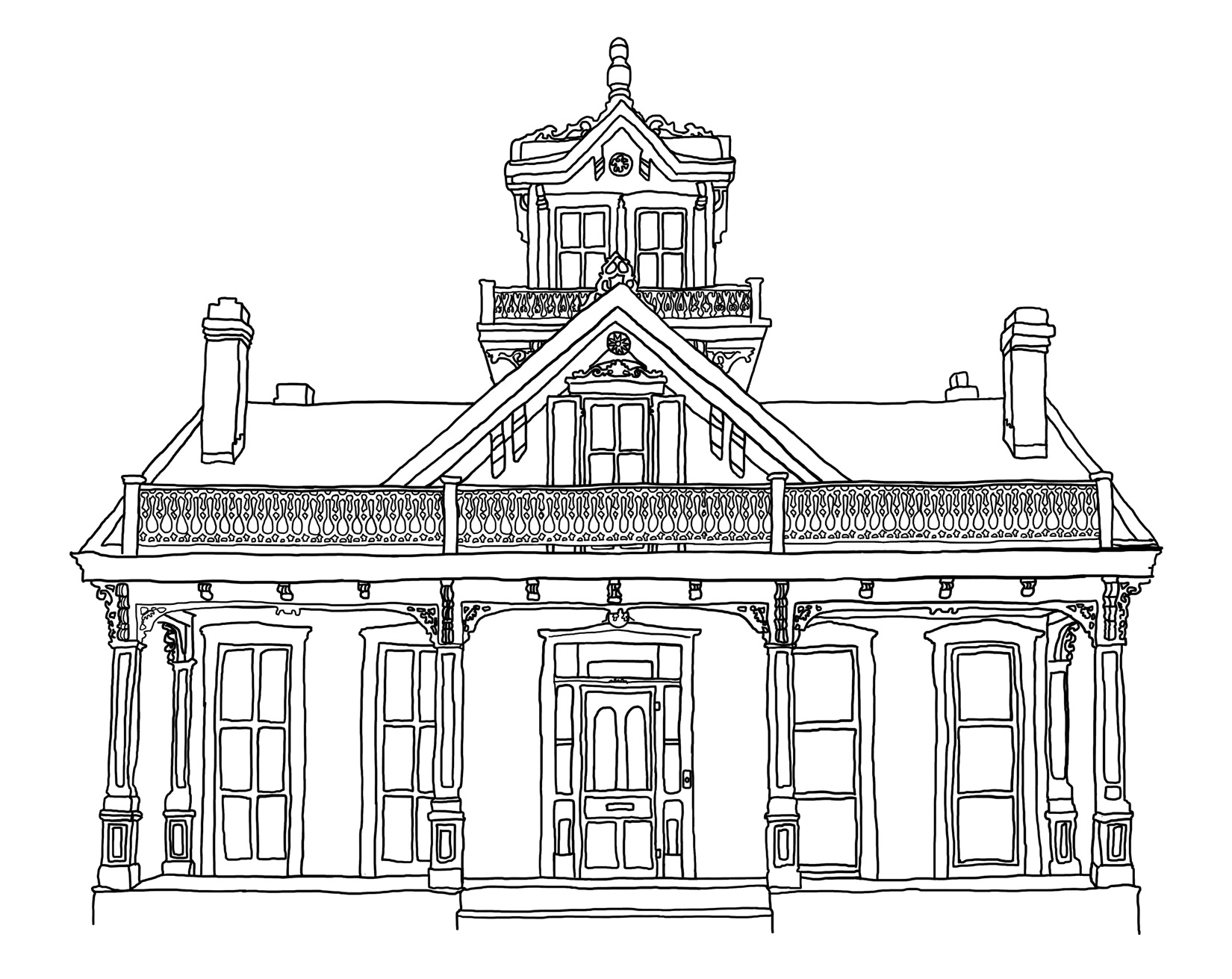

Inside, she would travel from room to room looking for something to clean or to shop for but never buy. In the kitchen, she’d bake all the time, trying new recipes for pie that she would then fully and entirely consumer for all three meals. Perhaps that was her favorite room. Or perhaps she liked the grand stairwell most; it led up to an empty hall where she would sit sometimes, gazing out of the window at the end of it.

The stairs were almost always dusty despite her always wanting to clean. There was something about dusting the stairs that seemed stupid, so she never did it.

And for years she was the only one traipsing through the house and maybe at the end of everything she was just lonely in a way that could never be fulfilled or satisfied. She tried sage and horseshoes and feng shui. Weird flower remedies and botox and happy lamps. Sometimes, she thought, it was the house at the root of the endless sadness. Perhaps it was cursed.

lilian edinger

She was trying loss therapy. It was something she had heard about on NPR after a segment on rejection therapy, which followed a segment on learning how to let go of violent thoughts by way of an ex-surfer holding a knife to his wife’s throat or pretending to strangle his dog, depending on his mood.

While rejection therapy was interesting, it was also too familiar. She was accustomed to receiving rejection letters regarding employment opportunities or never hearing back form potential boyfriends on OKCupid. But having lost very little in her life so far, loss therapy, though not entirely unlike rejection, was different because it allowed her to focus on losing things, like a penny or dish, or sometimes something more critical, like her house or car or dog.

Through loss therapy, she could also control the loss—the variety, the type, the where and when—and she appreciated this aspect of the program. She tried to lose something every day. That way, when she lost something important, something beyond her control, it wouldn’t be so bad.

From another perspective, and how she often justified her careless plate breaking, was that losing her things gave her reason to replace them with new things that would then be lost, thereby satiating her shopping mania, a topic that will be discussed next week. Stay tuned.

See Hamnett House Histories’ continuation here.