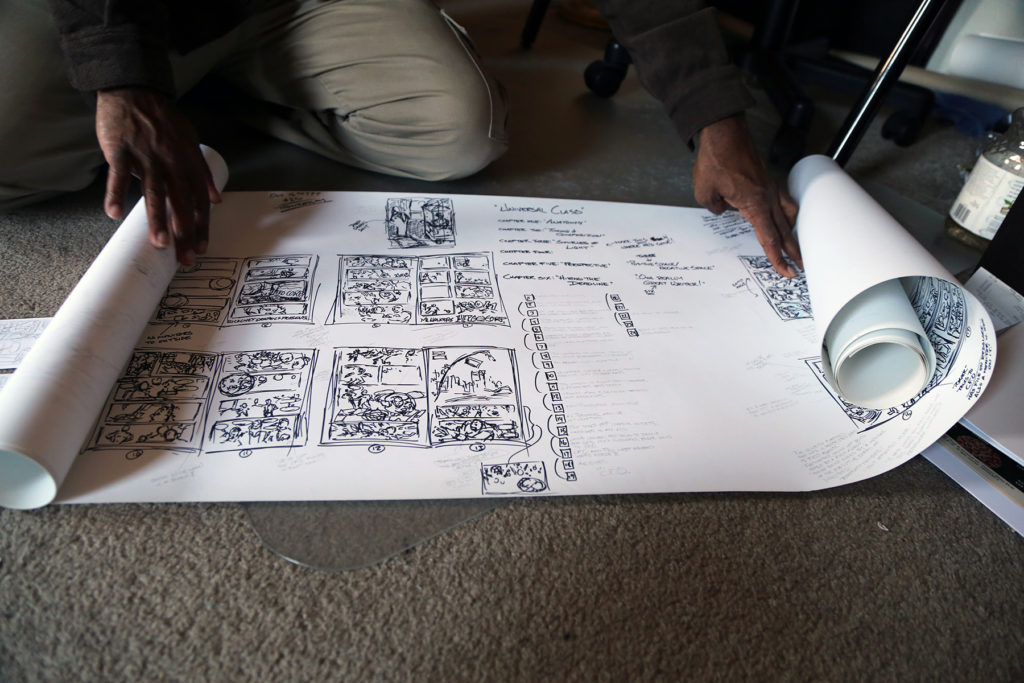

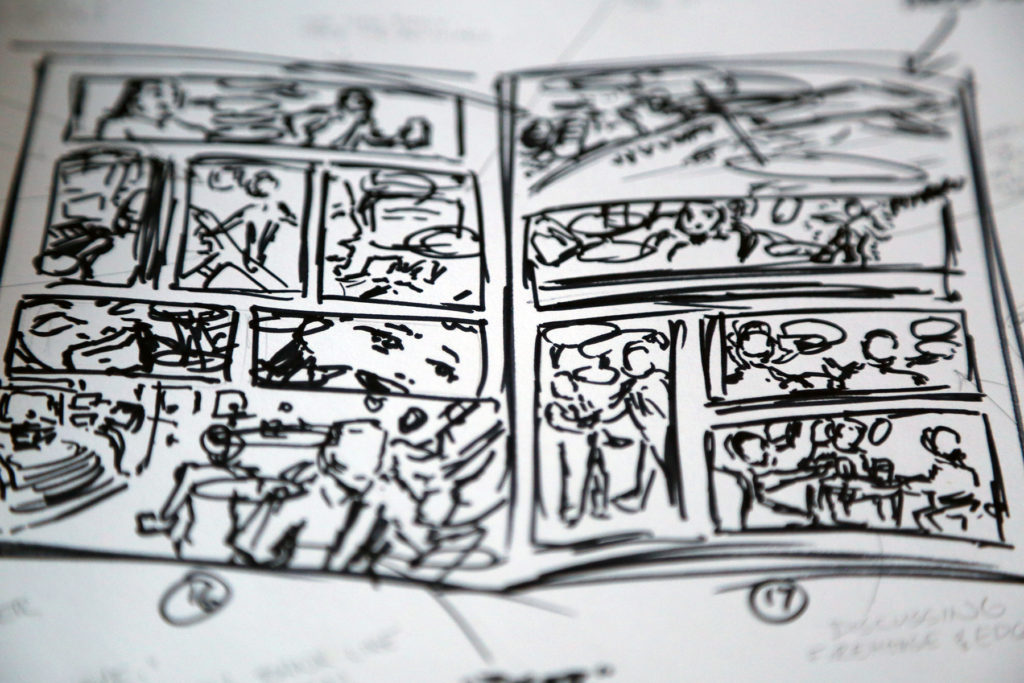

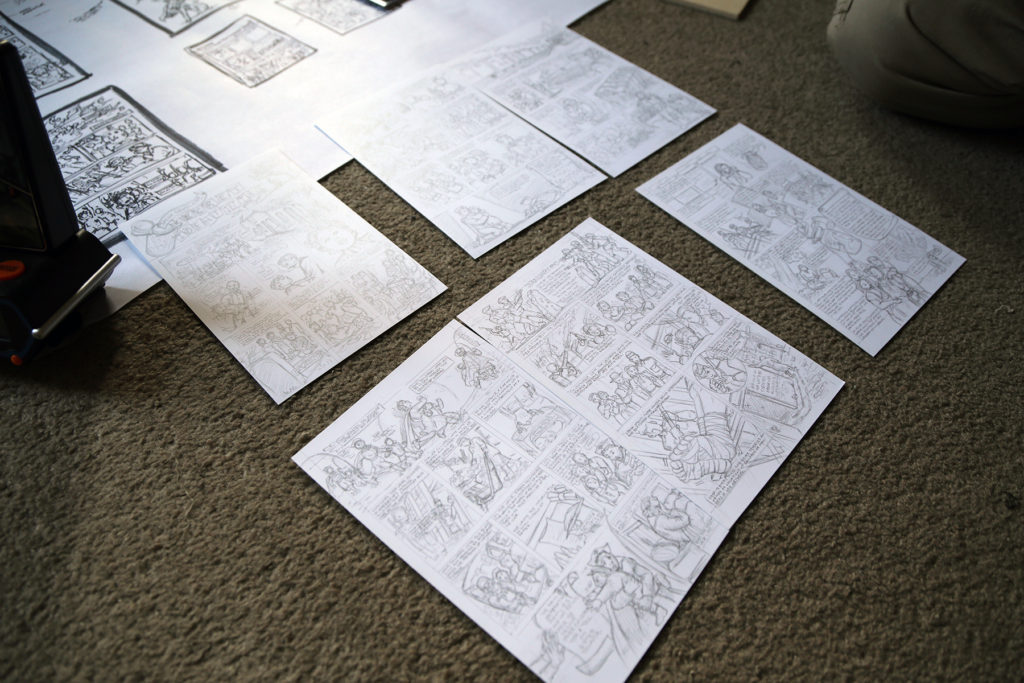

Illustrator and comic book artist Marcel Walker’s abode is lined with collector’s items—books, figurines, posters, miscellaneous superhuman ephemera. Doubling as his studio, this inspired home is where Walker crafts his Hero Corp. comic and works in multiple capacities on the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh’s Chutz-Pow! series. As we pored over over multiple iterations of his comics, from initial sketches to final, inked drawings, Walker and I discussed the discuss the long gestation of Hero Corp., how our favorite superheroes work for corporate America, and the importance of education and history in the Chutz-Pow! series.

![]()

David Bernabo: How did you become involved in Chutz-Pow!?

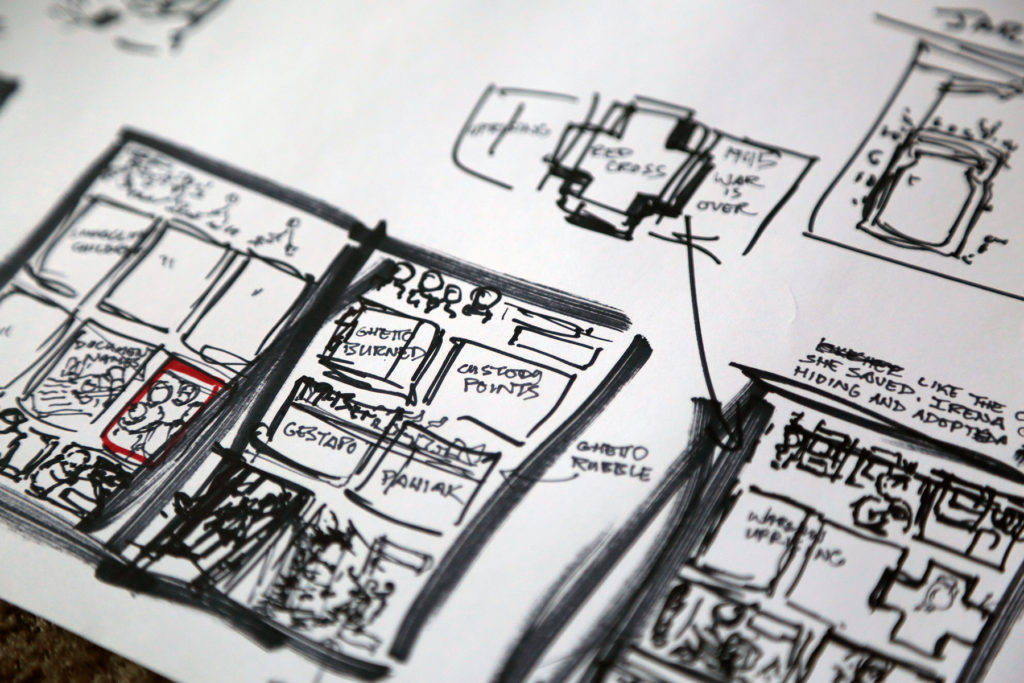

Marcel Walker: The Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh initially reached out to Toonseum downtown. They discussed ideas for utilizing comics’ art in the Chutz-Pow! project. Basically, they wanted to reform Holocaust education utilizing comic art to create new ways of addressing the Holocaust—specifically, to re-frame it, to focus on survivors and heroes instead of the tragedy.

They formed a committee. [Former Toonseum director] Joe Wos, in his wisdom, also reached out to my friend [author and comic guru] Wayne Wise and brought him on board. What came about was a plan to create both a comic book that would detail the stories of regional Holocaust survivors whom we labeled “UpStanders,” which is the opposite of bystanders. Bystanders see things happening and they let them go. UpStanders are people who see things and become heroes. We also had a companion exhibit that would have artwork telling other stories.

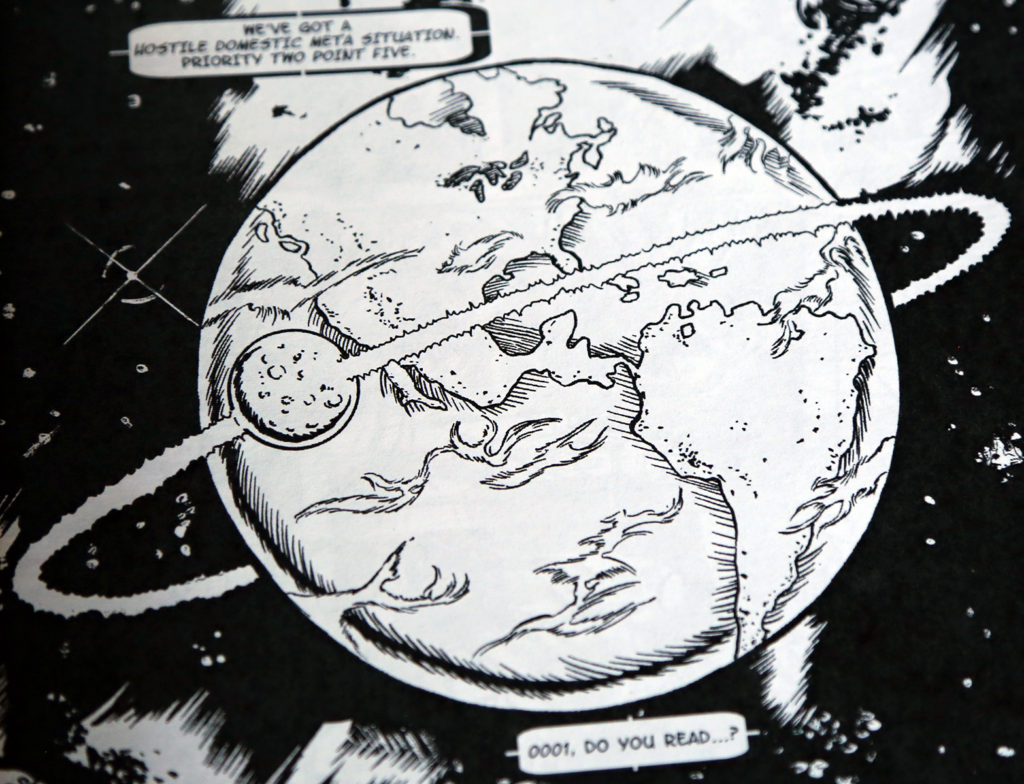

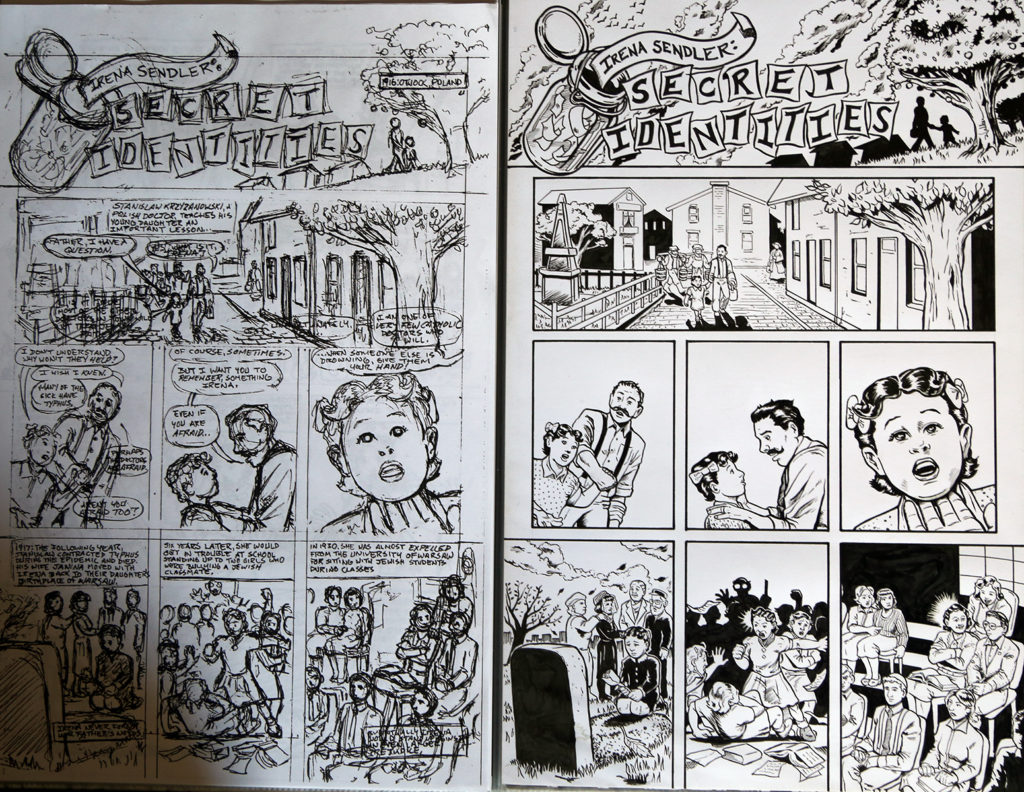

I was on a short list of artists that they contacted for both projects. Over time, my role in these projects increased. I eventually ended up as the lead artist on the comic book part of the project. I ended up drawing my story, which told the story of Malka and Moshe Baran, who were survivors who met and married, eventually moving to Pittsburgh and raising a family here. I also ended up doing lettering on at least one of the other stories, [and] text edits on others. I did all the layout and design work for the book. I also contributed an illustration to the art exhibit as well: a drawing of a Polish social worker during the Holocaust. All of the illustrations from the art exhibit portion focused on international heroes.

When it came time to do Volume 2 of Chutz-Pow!, we rotated [from the local heroes to the international heroes] as the characters who were featured in the second issue. On the second issue I did even more work. I drew a story, but I also wrote it. And this time I was the formal letterer on the stories.

It’s easy to look at [Chutz-Pow!] and dismiss it as a period piece. But I think it is more contemporary and more relevant now than even just a couple of years ago when we started on it. It speaks to all sorts of our social conditions that are present and have arisen in the past month or two.

DB: Can you tell me about your comic series Hero Corp.? When did you start writing the comic?

MW: Hero Corp. began its life about 15-20 years ago in the form of art submissions. For years and years, I was sending art submissions to various comic book companies, especially DC and Marvel, but others as well. I had, for the longest time, presumed that I was going to have a career drawing and creating mainstream comic and superhero books. I hit a point where I was sending submissions with enough regularity that I realized that there was a lot of work involved in being rejected. Every time you would send a submission, the rule of thumb was to create a submission using characters from that company. I should point out that at that time, most of these companies had open door submission policies. You could pick an editor and send them artwork to review—[though] that didn’t necessarily guarantee that they would see it or that you would hear back.

Eventually, I realized that I could save a lot of time if I created a generic character or set of characters that I could then submit to whatever company. It wouldn’t matter that [I didn’t use that company’s characters], because the submission would show my prowess at doing this. So, I created a submission that was based on myself, and it was very insider joke-y.

Also, I was doing art for friends and clients. Somewhere along the line, I did renderings of friends of mine as superheroes. It sort of gelled that they would co-exist as characters in this universe. In time, I began to think of the characters [actually] working together the same way that I worked with friends. Then the big conceit came along that these characters don’t just work together, but they also work together as superheroes.

DB: Do you have friends that ask to be in the comic?

MW: I’ve had some friends that have asked to be villains. If it feels natural and holistic, I do it. I’ve had a lot of friends that have asked to be superheroes and have superpowers, and I just nix it. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work.

Hero Corp. is meant for me to explain corporate America. Just to be blunt and honest, I have a lot of issues with corporate America. Most of us, in some way, shape, or form, work for corporate America. This notion that our favorite superheroes—Superman, Batman, Captain America, Wonder Woman—all these moral vanguards that we have distilled down to these icons and this iconography are not mythic, they’re property. They are owned by corporations. These companies profit off of heroism and our perceptions of heroism. Anyway, I love Superman. That’s my favorite character of all time, but I have to remind myself that I don’t own Superman. Time Warner owns Superman. We don’t own Superman. So, Hero Corp. is meant to address that—the notion that all these characters work for a corporation. They are restricted in what they can and can’t do, because the characters are essentially property.

DB: In Chutz-Pow!, you are investigating heroes from the past, digging up their histories, and showcasing little-known knowledge. What can comics do to educate and inspire given the backdrop of tensions in the U.S.—these tensions have always been there— like racism, sexism, transphobia, and ableism, which have been validated and encouraged by the incoming administration?

MW: I view comics as a storytelling medium, as a window into an infinite number of subjects. Comics are naturally engaging because they are so direct. You can’t miss the point of a comic book. Comics will also generally be designed with narratives in mind, which is different than other art forms. Music doesn’t need to have a storyline, or a beginning, middle, and end, to still be music. Visual art often is not expected to have [storytelling forms]—sometimes an image is just an image or it is expected that the viewer will bring part of the narrative to it. That’s all valid and can still be the case with comics, but the majority of comics have stories that are being told to me. While my participation is necessary, the comics are engaging visually and, therefore, bring you into the narrative. So, comics can literally tell you how to do things and teach you things.

But comics can also teach you broader things. They can teach you about other segments of our society and culture. There’s a story that ran in EC Comics back in the ’50s. The story was called “Judgment Day.” It’s a science fiction story with a wonderful twist at the end. It’s a story with a social moral, [addressing segregation], that’s obvious—so obvious that the Comics Code Authority almost didn’t allow that story to be published. Fortunately, the publishers resisted that, they make a stink, and eventually the story was published. That’s an example of just doing your thing; tell that story because you know the moral is right.

There are clear parallels between the UpStanders featured in Chutz-Pow! and what we’re seeing take place in the world right now. There’s a lot of people that are rightfully fearful right now with the inauguration of Donald Trump. I’m hard-pressed to believe that this actually happened, particular in light of his overtly stated views and goals [that negatively impact] broad swaths of American citizens. Taken to their not-that-far extreme, this is how these dominoes started falling leading up to the Holocaust. Chutz-Pow! is a cautionary tale. Hopefully, we can see enough of this coming to avert that. That said, I never thought we’d be where we are right now. But if Chutz-Pow! has taught me anything, it’s that we can overcome what appear to be insurmountable odds. You know, we don’t get anybody back, so we have to do everything we can to preserve the livelihoods and dignity of everybody we’ve got while we’ve got them. It all begins and ends with education. The more you know about these things, the more prepared we will all collectively be in averting more racism, more sexism, more transphobia, more ableism and coming together and living the way we should be.