Much of today’s discussion on local art centers on a few topics: sustaining a living as a Pittsburgh-based artist, creating equity in opportunity, energizing a local art market, or fostering critique. Studio Visit is a series intending to contribute to this discussion by spending time in-studio with artists, their work, and their thoughts on a creative life.

![]()

A few years ago, the Bunker Projects art gallery emerged on the Penn Avenue arts corridor to provide a new outlet for all types of artists to experiment with their craft. Part of their mission includes a residency program that offers live/work arrangements for visiting and local artists, culminating in a gallery exhibit. Based in Buckhannon, West Virginia, interdisciplinary artist Ellen Mueller is one of two artists currently in residence at Bunker Projects, and she has been busily preparing for her residency show What It Takes, which opens on December 2.

Dealing with themes from the environment, consumer culture, news media, and corporate structures, Mueller’s work for this exhibit involves video, sculpture, laser cutting, and performance. The Glassblock dropped into Mueller’s temporary studio at Bunker Projects to discuss her upcoming show, the appeal of artist residencies, and our thirst for infinite expansion.

Ellen Mueller: The main through line for this upcoming exhibition is the idea of deconstructing the cheerleader as an archetype, taking apart the physical attributes—the uniform, the pom-poms, the shoes—and also looking conceptually at what is the cheerleader. They’re both leaders and followers, because they all have to look and act the same, but they are tasked with leading us as a larger crowd.

DB: Does that apply to other types of cheerleaders? Politicians?

EM: Definitely, definitely. I started this project before the election, and I had to change it drastically. All of my materials were red, white, and blue, and they had a giant “USA” across them. This was because I was interested in addressing the idea of a political cheerleader, but now, it feels a little heavy-handed. I’m sticking with the cheerleader idea, but I actually ordered new uniforms [laughs]. No longer red, white, and blue. They’re black and white, which could be perceived as mournful, but I don’t think [these colors] are forcing the participant to adhere to my patriotic theme. It can be interpreted in other ways now.

DB: Can you break down the elements of this show? You have video work…

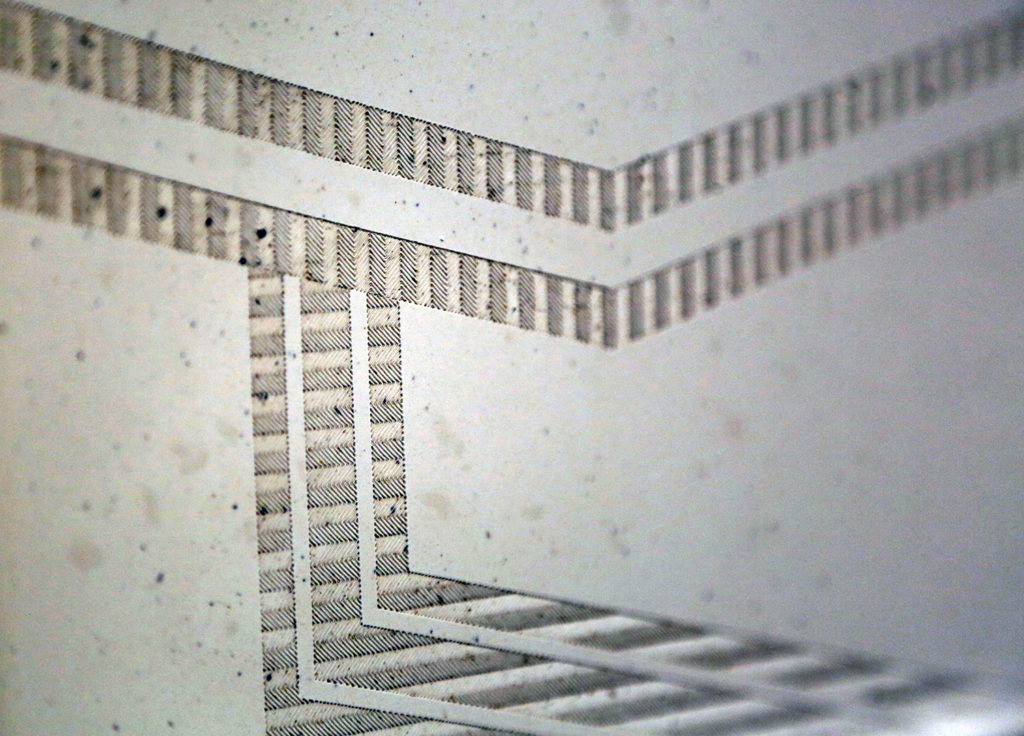

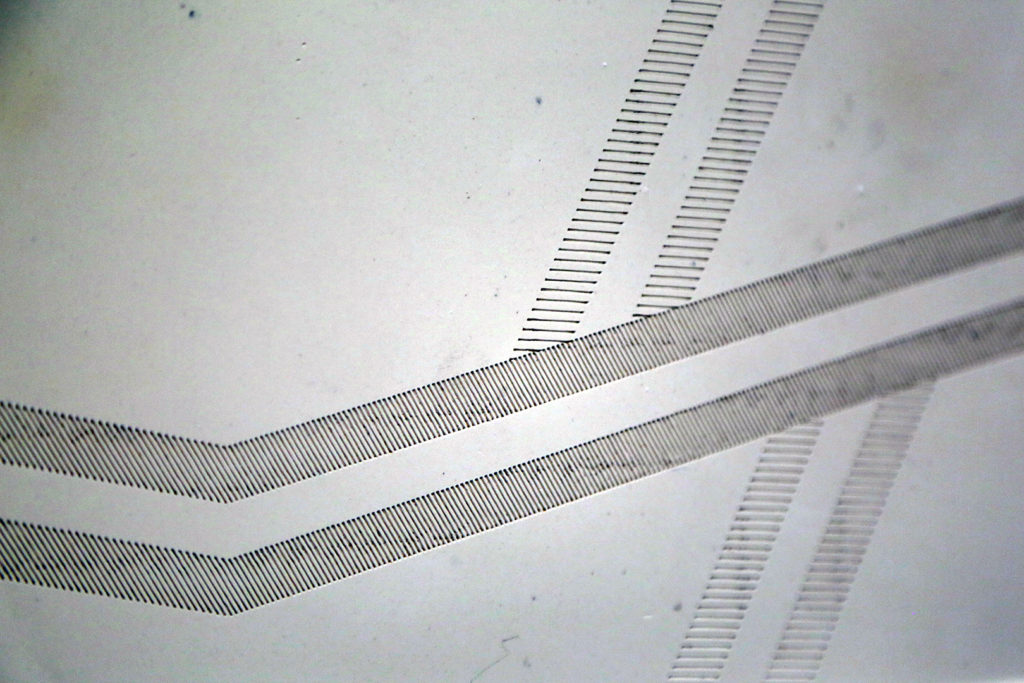

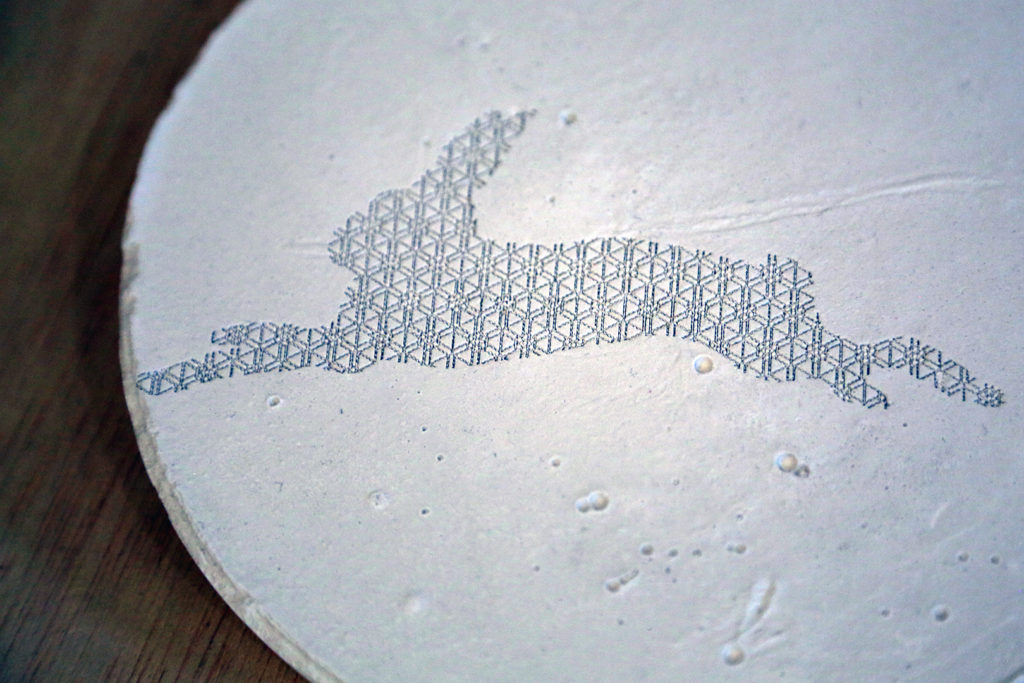

EM: There are three videos. [In-process edits of the videos displayed a stylized multi-panel, multi-shot video of hands disassembling the cheerleader uniforms and accessories.] There are drawings on poured plaster slabs, and I’m using the stripe and chevron patterns from the uniforms as inspiration for these compositions. The patterns are laser-etched. They are fun to get close to, because the light shifts.

DB: Ah, I just thought these were prints! Is there a performance aspect in the exhibit, too?

EM: Yes, my undergrad was a double major in art and theater and design technology. Those interests grew in tandem. So… I love the theater! [laughs] And I love performing and directing, so that leaks into my art practice all the time. I’ll oscillate from working on something solely alone—quietly, hermit-like—to doing something with performance because I really enjoy the interaction with people.

DB: Do you drop into a different mentality when performing, as if performance is a way to get out of yourself?

EM: Absolutely. Well, you’re accountable, too. I definitely have to think about what I’m articulating and why. If I’m going to invite the public to interact with me, I need to be really clear on what I’m saying.

DB: Performance seems a little less controlled than the visual studio practice. Well, unless you are very well-rehearsed.

EM: The performances where I take on a persona or character—yes, those are pretty well rehearsed. If someone approached during one of the Practical Preparedness performances from a couple years ago, I would hold onto my 1960s stewardess character. But for the performance that we are doing for this show on December 2nd, we are going to be taking apart cheerleading uniforms as a group, a communal ripping. There, I don’t see myself as a character, more [of a] comment facilitator. And that’s a challenge, too. You have to stay on your toes and be an active listener.

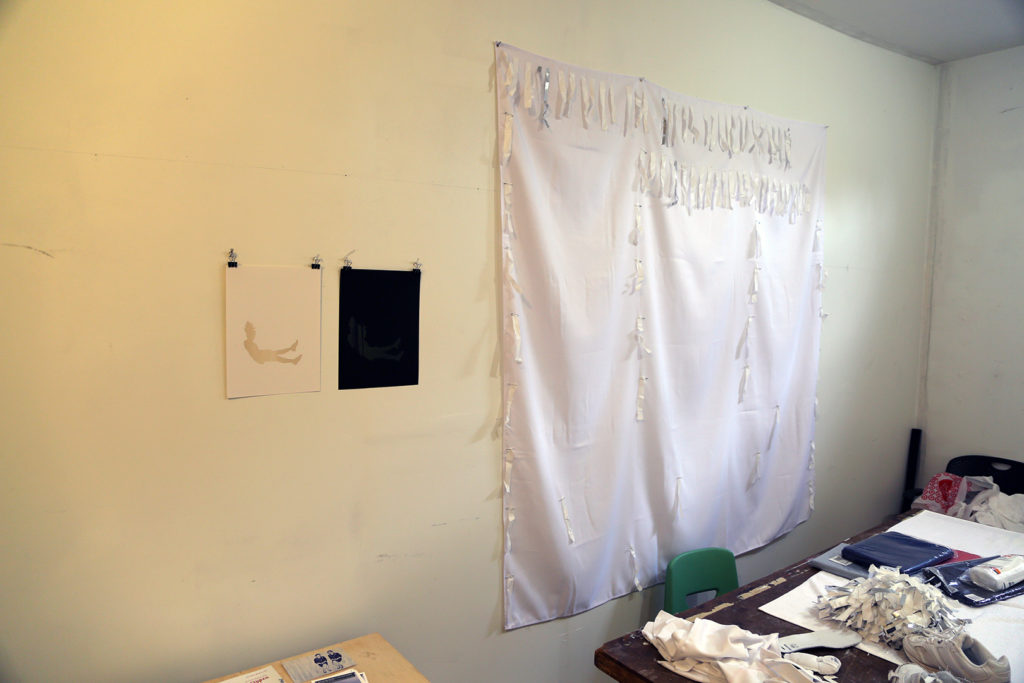

EM: [Pointing to a large sheet with safety-pinned strips of fabric] This one is in-process. I don’t know if it is going to make an appearance. After the election, the whole safety pin thing became a totally charged object. [I thought] everything is out of my control. Nothing is what it meant before. [laughs] But someone came in yesterday and said that it might be an interesting projection surface for the videos. So, that’s an experiment that I’m going to play with next week.

DB: That could be cool, especially if the video reflects off of those shiny pom-pom strips.

EM: Yeah, I was thinking that this may actually complicate things in a really interesting way.

DB: So, you are in Pittsburgh because of the Bunker Projects residency. Can you talk about the appeal of the residency from an artist’s perspective?

EM: People come to residencies for a variety of reasons. For me, right now, I’m situated in a really rural location. I’m in the middle of West Virginia, a small town of maybe 5,000 people. There’s not an enormous arts community there. Whenever I have a break, even if it’s a week, I’m applying for different programs so that I can get out and meet people. Sometimes I feel stuck in my own wooded bubble.

If I’m being totally honest, as a teaching artist I feel confident saying that I make no work during the school year. So anytime I’m not teaching, it’s all about getting my art done. I’ve done one or two of the isolated residencies, and I like working alone, but after about two weeks, you start to feel… different. It can be so self-focused like tunnel-vision. The Bunker Projects residency has two people, and it’s so lovely to go next-door and pop-in with Emma [Safir, another current Bunker Projects resident]. It’s beneficial to have a sounding board. So many of the relationships that I’ve made while at residencies multiply and turn into other opportunities afterwards.

DB: Does it help that residencies are a sanctioned space for making art? Sometimes I feel guilty for making art when I could be earning money, but the residency basically instructs you to make art.

EM: That’s a wonderful way of framing it. I grew up in Fargo, North Dakota, which is somewhat of a conservative area. Fargo is far more liberal and open than the majority of North Dakota, but there’s always a question like, “So, you’re becoming an artist? Why? What is the point of that?” But the residencies say art is important. This is helpful especially in light of major world events where I question myself and ask should I be [making art] or be out there doing something more [direct].

DB: But a lot of your work takes on corporate settings and addresses neoliberalism and other systems that impact those larger world events.

EM: Definitely. Questioning why we do things and what makes us happy—those are threads throughout my work. One of my recent projects, Vanilla Utopia, was poking at that idea, asking people what are the barest bone things that you need for utopia. It was really interesting to hear what people said, from surface level answers like coffee to more thought-out answers. But the exercise of thinking about [those needs] underlies a lot of my work. Why are we the way we are? Why do we live in a capitalist society? Why is the individual so important in America? And is it?

DB: I was interested in your work dealing with excessive consumer culture. That’s something that is so tiring—so many messages pushed on you, being conditioned to want things constantly. I mean, I have a problem with buying records and books. I wasn’t born with that interest.

EM: It’s how we construct our identity when you live here, and as globalism spreads, in the world. It’s considered important that you define yourself in terms of what you consume, whether it’s music, books, clothes, art. What is the printed matter that you surround yourself with? Who are you if you aren’t consuming?

DB: It’s interesting to pair your work, which is documentation of consuming, to some extent, with things like Instagram, which is a different style of documenting consumption.

EM: Totally. There was the one guy, Hasan Elahi, who was being followed by the FBI, so he ended up documenting and uploading everything from meals to purchases [to prove his innocence and provide the FBI with transparency into his whereabouts and purchases]. Everything went directly to his website. That spoke to me. Also, while I was living in Minneapolis for three years, I was living in a cubicle situation, managing a call center. That was very impactful, even to this day. That was probably 7-8 years ago.

DB: Those experiences don’t leave easily.

EM: Becoming an instrument of that system, speaking in the voice that you are trained to speak in, carrying yourself and dressing yourself in the way you are supposed to for that situation—you become confined by that. I wonder if there is a frustration with that throughout society.

DB: You take on different measures of what success is.

EM: My graphic novel work, which is more narrative, wrestles with definitions of success and our end goal.

DB: Eternal expansion!

EM: Growing forever!

DB: Did you get to see Pittsburgh much in the past few weeks?

EM: I got to see so much, and that was one of the driving factors for me coming here. Pittsburgh is the nearest metro area for me—about 2.5 hours away—and I wanted to invest myself here. I wanted to know which institutions I was interested in and which places I should make a point of coming back to. So far, I’ve loved everything that I’ve seen. I went to the Hélio Oiticica show. That was such a fantastic show. Oiticica is frequently mentioned in performance art texts, so it was great to see that work. Also, I’ve never seen the Carnegie [Museum of Art’s] general collection. It’s very good—lots of artists that I was like, “Oh my gosh, they’ve got one of these, and one of these.” I went to the 707 and 709 Penn Galleries downtown, and I was really impressed that there are these two little spaces right downtown that are really nice galleries.

DB: And pretty accessible for local artists who want to exhibit work.

EM: Yeah, I love that this city is supporting artists in that way. Also, I didn’t know it was Light Up Night that night.

DB: Oh no!

EM: So many people. But I did get to see the lit-up bridge that Andrea Polli [in the piece Energy Flow] did with the dropping lights interacting with the wind. And this is my geeky side: I was so delighted that the next day I could go to her talk. But doing those kinds of things is delightful to me. It’s probably not notable if you live in Pittsburgh, but to me, it’s novel that almost any day of the week, you can go do something or see something and get this burst of inspiration.