This Sunday, the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council has big plans. At 3:00 p.m., they will be serving a free, family-friendly meal to 500 people in front of the City-County Building in downtown Pittsburgh, part of a larger Sunday Supper event that includes local entertainment, a community-driven policy discussion, and, of course, food—which is sourced and prepared by 412 Food Rescue and Community Kitchen Pittsburgh.

The Pittsburgh Food Policy Council (PFPC), which formed in 2009, aims to improve Pittsburgh’s regional food systems. From growers to distribution centers to grocery stores to restaurants to home cooks to waste disposal personnel—food systems contain a lot of moving parts. Each entity in the chain is enmeshed within a host of complex relationships of economic sustainability, ecology, and access and equity to goods and jobs. The PFPC serves as an advisory committee to help ensure that our food system benefits the community, the environment, and every person along the way.

I met with Dr. Stephanie Clintonia Boddie at Zeke’s Coffee in East Liberty recently to discuss the local role that the PFPC serves. Dr. Boddie is on the PFPC’s steering committee and serves as the co-chair of the Regional Food Economy working group. In addition, she works as a consultant and adjunct professor in the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary’s Metro Urban Institute. At Zeke’s, Dr. Boddie and I discussed the goals of the PFPC and specifically her work with the Oasis Foods project in Homewood.

![]()

David Bernabo: What are the goals of the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council?

Stephanie Boddie: The Food Policy Council’s goal is to build a food system that benefits the community, the economy, [and] the environment while being equitable and sustainable. The Regional Food Economy working group is focused on two primary issues—procurement [of food] and the workforce—[which] are less obvious to people.

I don’t know how often people think about how the food system is impacting the people that help get our food to the table: the farmer, the person that works in the grocery store, the waiter or waitress that brings our food to the table. These are people impacted by the current way the food system is set up, and too often this population is food insecure or may be working in an environment that is not safe or reliable. So one of the things that we want to do with the Food Policy Council is to define the conditions in our region for food workers. The food worker landscape has changed. In the 1900s, most of the food workers were farmers. But now, most of the food workers are probably service workers, many in fast food restaurants.

DB: Is the organization primarily a research organization, or does the group advise or take steps to implement actions?

SB: Our goal is to inform and influence policy. Without good research as a baseline, it is hard to effectively inform policy. We are part of a larger network of national food policy leaders. We can’t say that what is going to work in Los Angeles or Baltimore is going to work in Pittsburgh. So, we need to understand our context.

DB: One thing I’ve found from talking to people in this field is that food security and hunger are more closely tied to income equality issues instead of food distribution. How do we solve hunger when there are bigger systemic issues causing hunger?

SB: Right, that’s one of the reasons that food workers are important to us. Many of the people serving our food are not making adequate wages. While we know that about 25 million people [in the United States] live in food deserts, many times these communities are places that do not have many living wage employment opportunities. And people don’t necessarily have the transportation to get to living wage jobs because there is a disconnect with the transportation system. When you talk about food insecurity, the food system intersects with other systems, particularly employment opportunities and stagnant education. If people do not get a quality education, then the pipeline that they are fed into is not a high paying job. It’s either low employment or unemployment.

DB: With Pittsburgh focusing on medical and tech jobs, that education is a major need.

SB: It’s definitely a challenge in Pittsburgh. With the universities and social innovation on the medical and tech sides, hopefully there will be ways to bring that innovation into our public school system to create a more equitable system so that this is truly a Pittsburgh for everyone.

DB: Can you talk about your work in Homewood with the Oasis Foods project?

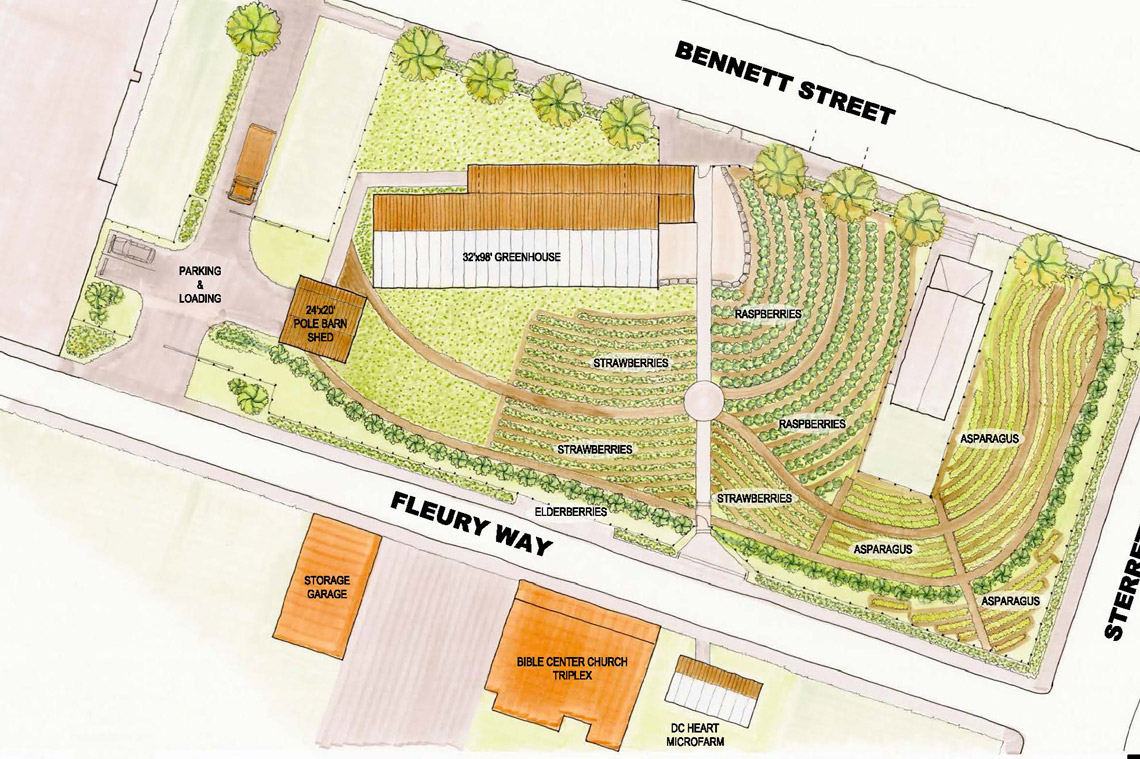

SB: The Oasis Foods project is a partnership with Bible Center Church, among other partners, to create a food hub. Bible Center Church has been in Homewood for 60 years. The pastor is Dr. John Wallace, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh. He has a real passion for the church being an institution that can serve the larger community. Through his affiliation with the university, there is a partnership with the School of Business and a program called DC Heart, which is bringing solar energy to low-income communities. We built a bioshelter in Homewood, and we will be launching an aquaponics system in it. We’ll be growing soilless vegetables and plants while raising tilapia. In an aquaponics system, the excrement from the fish provides the nutrients for the plants.

DB: And that can grow food year-round?

SB: Yes!

We also have a partnership with GTECH. We were part of their Green Playces program where we built an outdoor classroom and kitchen. We also have raised beds, places to sit, and a place to show films. We are also in the process of launching Everyday Café, which will be a cashless cafe near the busway in Homewood. With these components, we hope to be able to hire locals and train youth and young adults in various things from working in the cafe to learning about urban agriculture to learning about DC Power. Then, we are looking at opportunities to learn from these experiences to develop a commercial farm. Workforce development, job training, and education are all part of this project.

DB: It sounds like you are trying to address short-term food needs in addition to longer-term systemic fixes.

SB: Right—if we can expose people to new opportunities like aquaponics, people might not go directly into urban agriculture, but that exposure to new technologies might provide an easier transition into other types of employment that might be at a higher wage than working at McDonald’s.

There’s also the added benefit of being a part of a project where you are getting after-school support or mentorship. Participants may do better in school and find things that they enjoy that sparks them to improve their grades and aspire to a certain profession. Maybe they will realize that they want to be a chef or that they want to go to college and learn about nutrition and become a physician’s assistant or a doctor. They will be learning new things, but they will also be exposed to other types of professionals, because they are part of this new food ecology—the mix of food, technology, art, culture. The project can expand the [worldview] of these youths, providing new opportunities that aren’t currently available in and around Homewood.

DB: How does the risk of gentrification impact these community efforts?

SB: The question is how do the people of Homewood—the people that live, work, worship in Homewood—how do they reinvest in the neighborhood? How do they attract other partners that want to work on reimagining the main street? So, having a coffee shop near the busway can make a big difference in the community. The dollars can circulate a bit better within the community. Right now, the food dollars, outside of the few Homewood restaurants and convenience stores, are not circulating within the neighborhood. If people want to go out to a sit-down dinner, with a few exceptions, they have to leave Homewood, and their money circulates within another neighborhood. It’s important to figure out how to keep money circulating within Homewood.

Going back to Oasis Foods, one of the reasons that this name was chosen is because it’s about creating a place of peace, safety, and happiness in Homewood. Many people Google “Homewood” and the first few things that come up are not necessarily the words, “peace, safety, and happiness.” By developing Oasis Foods along with some of the other good work happening in Homewood, we hope people start to think of Homewood as a place where people can be inspired and make things happen.