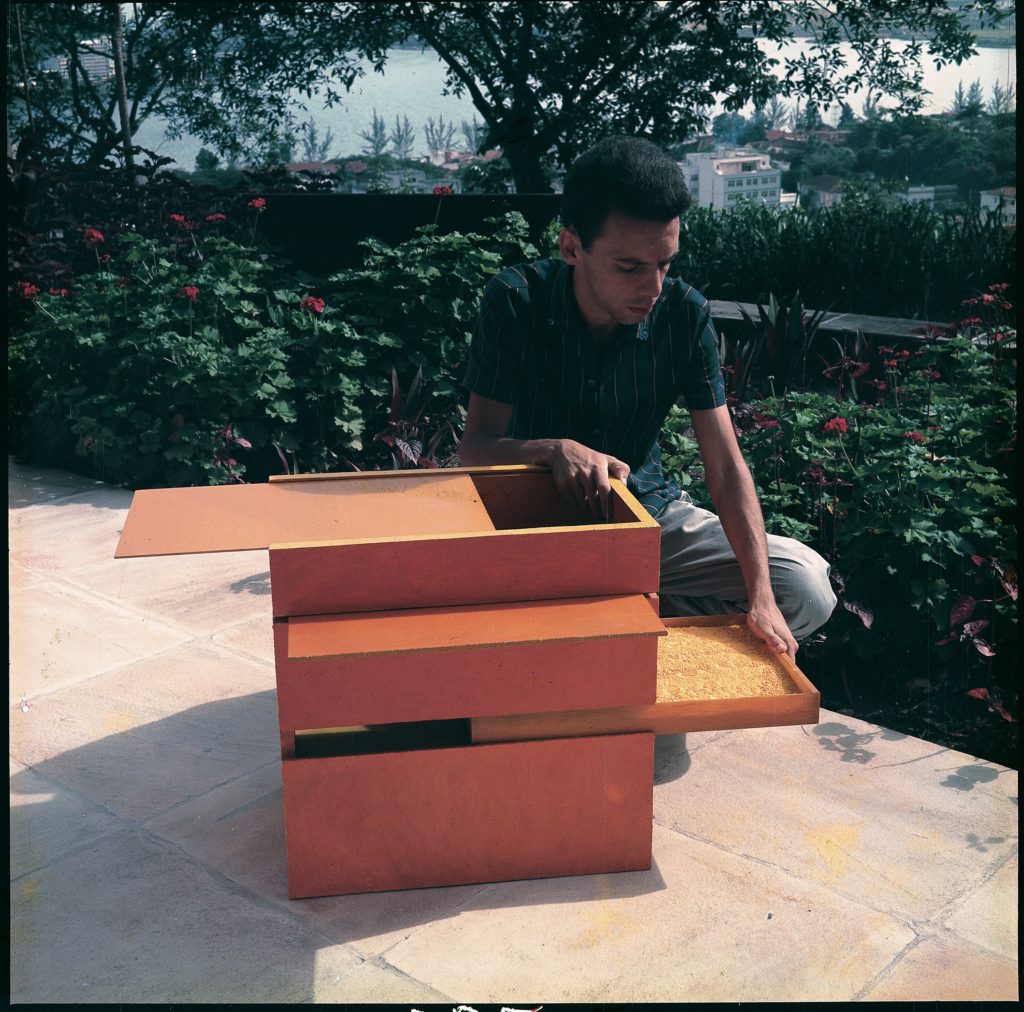

On October 1, the Carnegie Museum of Art will unveil a “comprehensive U.S. retrospective of the influential Brazilian artist” Hélio Oiticica. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1937 and influenced by the Brazilian avant-garde, Oiticica traveled between Rio and New York throughout his life, developing his style today known as Neo-Concretism, or geometric abstraction. With a foundation in the Rio artist school Grupo Frente, his early paintings from the late ’50s portray vivid colorful geometric forms, but by the the early ’60s, Oiticica had evolved his approach toward the 3D with small boxes crafted out of wood that he called Bólides (or “fireballs”). The Bólides were small enough so that viewers could physically interact with them, manipulating sliding panels to create new spatial and color arrangements or reaching into them to feel objects or materials. Similarly, Oiticica’s Penetrables relied upon the participant to activate the work—but these were large, framed structures, made of rooms and corridors and colored Plexiglas panels or fabrics, through which viewers would explore on their own. His series of Parangolés took viewer activation a step further: these were art pieces made of fabric and other materials intended to be worn on the body, inspired by the Mangueira favela samba dancer costumes.

After its Pittsburgh debut, Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium will travel to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. In advance of the CMOA opening on October 1, we sat down with associate curator Katherine Brodbeck and media relations manager Jonathan Gaugler, and at a later time with CMOA director Lynn Zelevansky, to discuss curating Oiticica for multiple audiences, the artist’s use of performance and participation, and more. Our interviews have been lightly edited and compiled below.

![]()

DB: When you curate, who is the show for? Do you curate for a national audience? Or does the fact that that the exhibit takes place in Pittsburgh require a responsibility to a specifically Pittsburgh audience?

Lynn Zelevansky: You’re right that curatorial programming is a question of balancing the interests of different audiences. I felt that the Oiticica show would be important to Pittsburgh for several reasons. Latin American art from the mid-20th century hasn’t received the play in our Carnegie Internationals that it might have, so Pittsburghers haven’t been exposed to it here. And, given our desire to attract international residents to the city, including Latin Americans, I felt that we should do more in that regard. Exhibitions like this—shows that feature artists who’ve made a significant contribution internationally, but remain under-known in the U.S.—are an important way for us to nurture the Pittsburgh art world. There hasn’t been a major retrospective of Oiticica in the U.S. in over two decades, and there’s never been one that traveled to these major cities, so it’s also a contribution to the cultural life of our country—a contribution that reflects back on Pittsburgh in a very positive way.

Katherine Brodbeck: I think it’s really great when a show is in a place like Pittsburgh and also New York, because you have to be responsible for both audiences. The wonderful thing about Oiticica is that he wanted to incorporate everyone into his art. So even if it doesn’t touch on the direct Pittsburgh experience (which he would have known nothing about), he always cared to engage local communities. Oiticica was not interested in just being in the artistic centers of the world; he really wanted to engage children and people who wouldn’t typically be in an art museum. The exhibit has such a natural connection to different types of communities, so I think it’s really great if people who are coming to this exhibition don’t know anything about Brazil—they’ll learn something about it, and hopefully in a way that is super approachable. The work is so much about engagement and participation and natural creative impulses that transcend regional references.

Jonathan Gaugler: I think there is a sense of resistance in his art too that’s really interesting and that, because we’re able to produce the Parangolés for the body, people can wear them and use them. We’re doing a community day in Braddock where we’re taking the pieces there [to let the community] try them and use them and find ways [to connect with some of the] messages like, for example, “I embody revolt.”

KB: “I embody revolt, out of adversity we live, sex and violence is what I like.”

JG: [Laughing] Not terribly specific to Brazil. I think that’ll be a lot of fun and [those works] will be in the show, too. Anyone who wants to can find a facilitator and try the costumes on.

KB: Oiticica was creating work during a dictatorship in Brazil, and in Brazil right now there’s been another coup, so it’s very relevant for the moment. But also so much of what he was talking about was—he made tributes to slain people that police killed—so there’s so much imagery that feels so relevant now, even outside of Brazil.

DB: This is a Carnegie Museum curated show that will be traveling?

KB: It’s co-organized by all three venues, the Carnegie Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and The Art Institute of Chicago. I think the Whitney and the Carnegie were the first partners and then the Art Institute was brought on. But we are co-organizers.

DB: What is the process of starting the dialogue between the museums and how you pick who pays for what?

KB: It really depends on the arrangements; they can be pretty complicated. But because Lynn had done a show co-organized with the Whitney before, when she first moved here, I think that was a natural partnership. The Art Institute also had a strong interest in showing this work, so I think that’s how this came about in Chicago. It could’ve toured somewhere else but it’s hard to keep the loans together for that extended period of time.

LZ: We are a team of four curators. We traveled to Brazil several times and to Europe to see works by the artist first-hand. We had many meetings, usually in New York as it was a place we could all get to easily. We discussed the checklist, all aspects of the book (which is quite ambitious), and the progression and layout of the exhibition. All of our decisions were made collaboratively, but most of the administrative and editorial work was done by CMOA, in part because we’re the first venue.

DB: What’s the duration of the three shows?

KB: So it’s three months in each place. With install and de-install the whole show is basically a full year, running until October 2, 2017. It’ll close in New York at the Whitney.

JG: We have loans from New York, from London, and a ton of stuff from Rio. Getting all of these parties to agree to [let these objects travel is a challenge], and every time something travels, it’s just another headache for a registrar somewhere. They’re very protective of the works in their own collections.

KB: It’s very fragile work, and a lot of it has organic pigments and things that are very difficult to show. It’s not just paintings. From a conservation standpoint, some of these works are very difficult. Also, because there was a fire at the artist foundation [in Rio in October of 2009], there’s so much less of this original work than there was ten years ago. That lends to the preciousness of dealing with the original objects.

DB: Could we talk a little bit about audience participation? When you deal with performance art, so much of what you show is the artifact of the performance or objects used in a performance and not the actual art. But it seems like so much of Oiticica’s performative work can be reproduced in some way. Can you talk about how you chose artifacts over reconstructions?

KB: We have, for most of the participatory objects, the original artifacts and exhibition copies or reconstructions. We’re showing both. I think that’s a very difficult decision to make, and even on our curatorial team there are different approaches, too. There are people who only want to show the artifact, and people who think that the artifact isn’t really communicating anything anymore. But what’s important about Oiticica’s work is that he had such strong formal training. Even the Bólides, which are things that are meant to be manipulated, are lovingly painted. So they’re not throwaway objects by any means. There’s a lot of care to that. Even if you can’t [interact with] one of the original Bólides in the way it was intended, the original still has a really stunning visual presence. When you can have both objects, a reconstruction that you can handle and the original that you can look at the aura of the artist’s hand, [then you have] both elements: the element of play and the beautiful formal rigor that he brought to the original object.

JG: For Oiticica, a lot of the work [only exists] when the object is being interacted with. The performance is in the gallery every day. These things only become art when they are being walked through or handled or opened.

KB: Oiticica died when he was 42. During his lifetime, I’m sure that he would be horrified by the idea of something like this [exhibit]. Oiticica was definitely not interested in museum relics, which some of these things have now become. But it’s hard to not advocate for the original material object if you can make it survive.

DB: With some of the recreations, there’s fabric with what looks like paint on it. When you recreate it, is the attempt to mimic the original mark or is it trying to mimic the original intention?

KB: The Parangolés are all fabricated originally by a woman who worked in the Projeto Hélio Oiticica named Ariane Figueiredo, who knew him during his lifetime and was the younger sister of the person who used to head the Projeto. So she used to recreate them, and she helped Oiticica sell some of them when he was alive. There is, at this point, a handing down of the traditions of how they were made. The paint on the Parangolés is less important for the paintbrush marks that you see on the Bólides, but I think at this point there’s still enough knowledge of how they were recreated that they are pretty faithful recreations. A lot of the Parangolés that get reproduced are the ones that have less of that element to it because they are easier to reproduce. They vary in terms of sophistication, and some of them have more painted elements than other.

DB: It sounded like Oiticica came from some amount of privilege. Did that continue throughout his life?

KB: He eventually went the traditional bohemian route [in that] he was living very precariously. But he did know that he had that safety net, so when he was in New York, he was living in near poverty, but he would sell his works back in Rio for money, or he would call his brother and his brother would wire money. So I think he had that safety net, but he deliberately chose the bohemian lifestyle [that we associate with] the late 19th century Parisians. I think precariousness was definitely his mode of being.

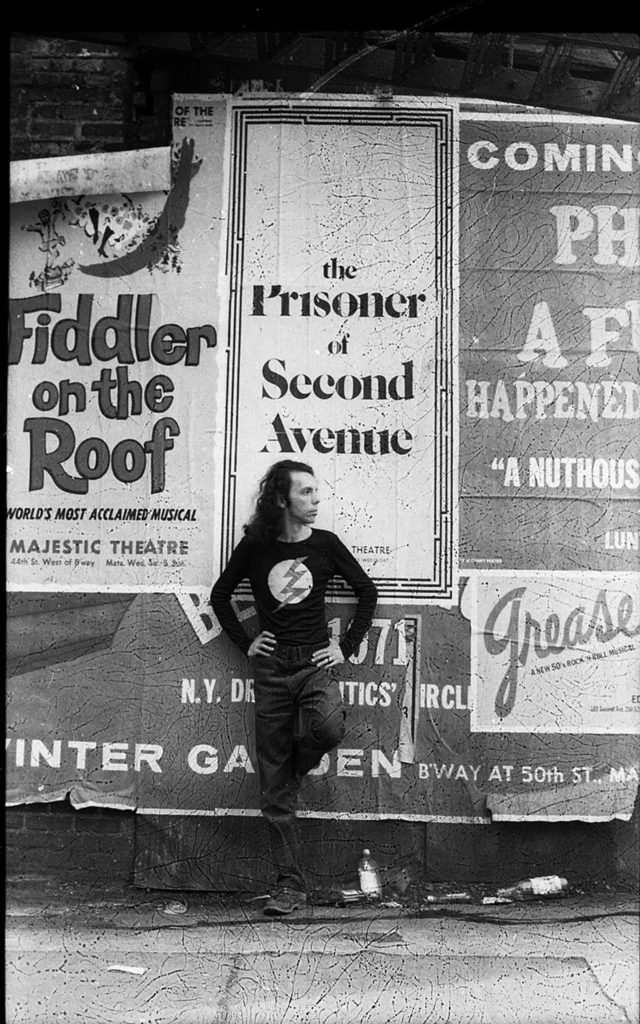

JG: In New York, he was not interested in Soho—he went straight to the Lower East Side, and then he decided to start mapping the gangs of the Bronx.

KB: He met a French photographer named Martine Barrat who did a lot of work in the Bronx and in Harlem and Oiticica saw a kind of parallel to what he had been living in in Rio. He made several visits with her. She was more engaged with the community directly than he was, but I think he saw that kind of parallel [to Brazil] and was really interested in it. So he was deliberately seeking out the parts of New York that felt the most marginal to him.

DB: I was surprised to learn that Tropicalismo was more than a music movement. I have my Gal Costa and Gilberto Gil records, but I never realized that the music was part of a bigger art and political movement, or that Oiticica was in on the ground floor.

KB: I mean, the music is so much more popular and famous than the visual art, so that’s the resonance that sticks out to most people. But Caetano Veloso will still wear Parangolés on stage even today. He has a fond memory of Oiticica.

DB: How many of Oiticica’s structures will there be in the exhibit?

KB: The biggest one is Eden, which is in the Hall of Sculpture and is going to take up all of the space in between the columns. And then Tropicália is also one that you can enter. You don’t actually take your shoes off, but there are paths, sand, and a cage with two parrots and two Penetrables that you can enter—one of them even has a television. And then there is Filtro, which is kind of a massive labyrinth that has these brightly colored Plexiglas walls, and inside there are sound elements and television and orange juice that you can drink.

DB: Fresh squeezed?

KB: Well, there’s gonna be an orange juice machine. I don’t think it’s gonna be fresh squeezed.

JG: The idea is that you’re taking in pure color, or this impossible experience of pure color, so let’s get as close to it as we can by ingesting it.

DB: Was there a discussion on not exhibiting it sequentially?

KB: Yeah there was, and it’s possible that the Whitney, for example, which has just one huge space, won’t do a chronological presentation. I think with our galleries being an enfilade, it makes the most sense to do it chronologically. Also, I think it makes the most sense because his work is very evolutionary; it builds on itself and returns to itself. So I really like seeing the progression, and I know Lynn always said she goes for chronology unless there’s a reason not to.

DB: Last question: Do you have plans for cleaning up the sand?

KB: [Laughing] I think that that is a struggle for everyone else involved—they’re all very annoyed at us. I’m being trained to take care of the parrots, but I don’t know how we’re cleaning up the sand. There’s gonna be bags and barriers, but I’m sure it’s gonna get very messy. Like [with our exhibit of work by] Alison Knowles, the beans got everywhere.

JG: Because kids love that thing. They flop on their stomachs and swim. But it’s about having people who can show people how to enter a work, where to go, don’t get lost in there, here’s how to put on this costume. It’s a whole separate skill set than simply, “Don’t touch that.” It’s more nuanced than usual.

KB: We’ll definitely have gallery ambassadors.

Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium opens October 1 and runs through January 2, 2017. CMOA’s exhibit will incorporate many related events—check them out here.