Artists dedicate significant time to each creation, and, often, reviews of artists’ exhibitions strive for a summation that can leave specifics unexplored. Our series The Object is a an attempt at a small-scale course-correction, focusing conversation on one single work of art in order to investigate its concepts, materials, and execution in great detail.

![]()

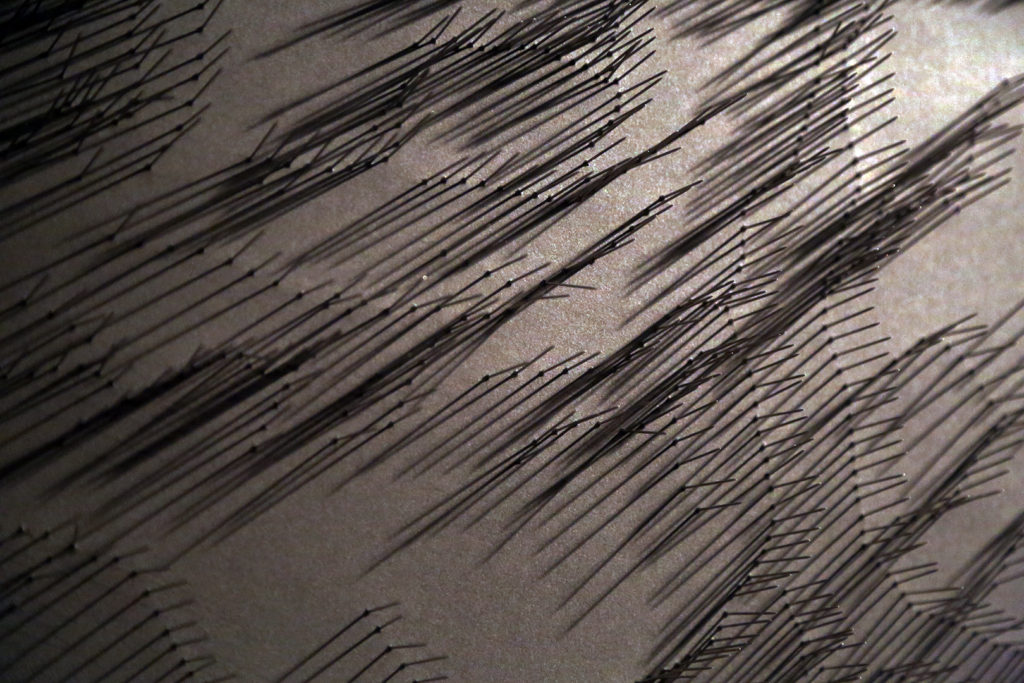

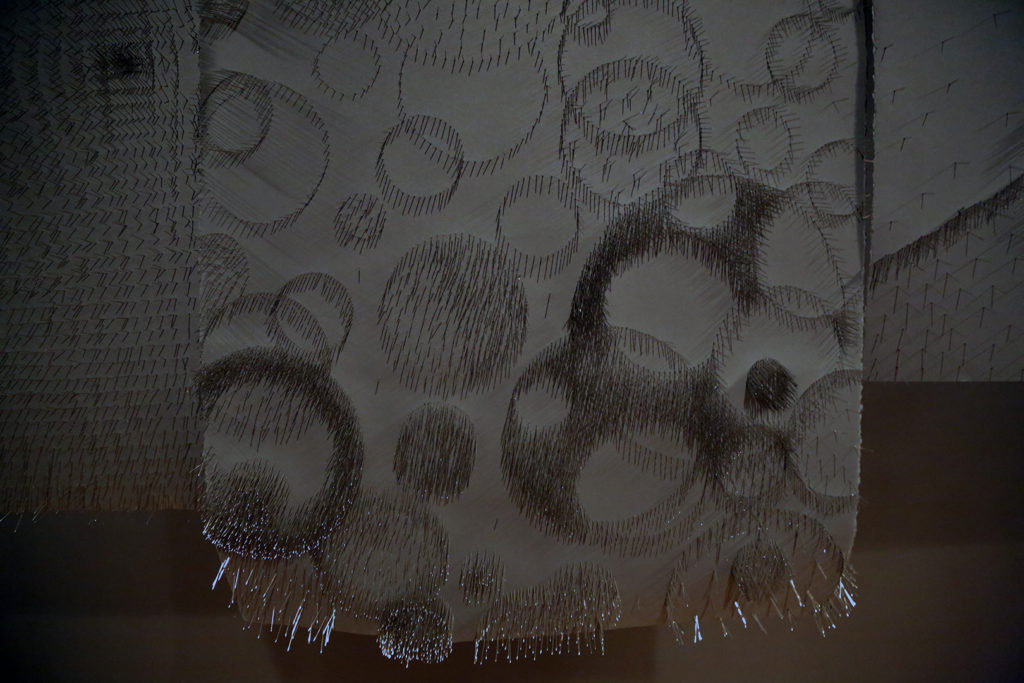

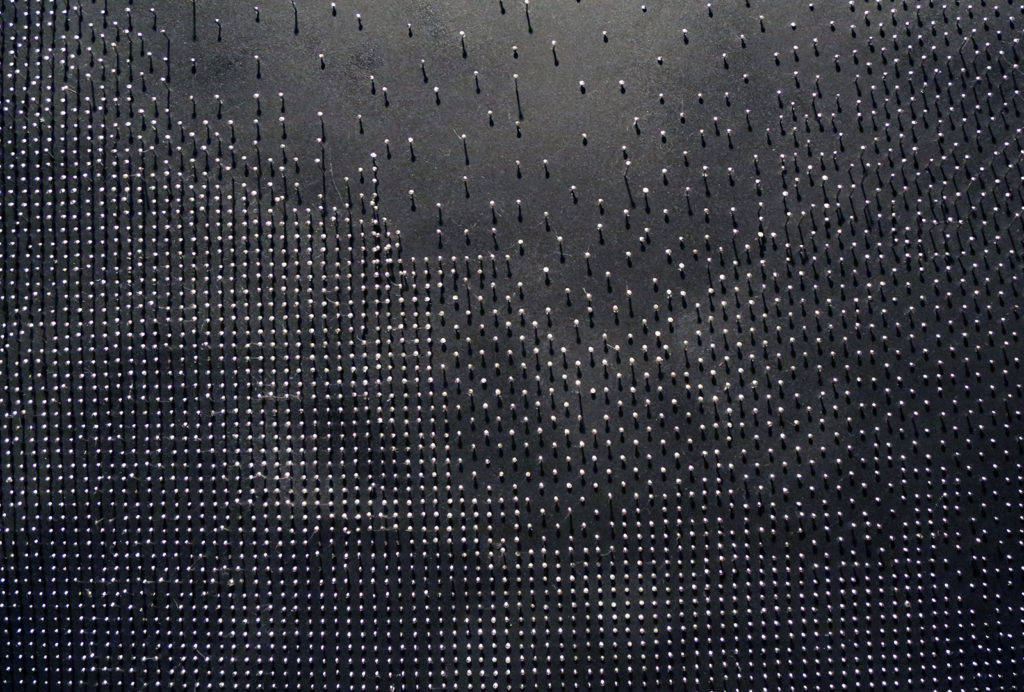

On the second floor of the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, black sheets of paper hang in a darkened room, arranged into a sort of enclosure. The walls are painted black, but a scattering of overhead lights reveals a surprising textural feature: Each sheet of paper is riddled with small pins. Within the enclosure, the pins point toward the viewer, while on the outside, recognizable designs—circles, grids, and dendritic neural patterns.

Sarika Goulatia’s installation Life is a great tapestry of pins drawn together in immense and miraculous patterns is part of her Dressed with D.R.E.S.S. Emerging Artist of the Year show at the PCA. Read more about Goulatia—with insight into how an adverse physical reaction to a prescribed medication inspired her sculpture-heavy show—in The Glassblock’s Studio Visit from last month. For our series The Object, installation artist Natalia Gomez and I visited Goulatia’s exhibition to focus on one single piece. Read our conversation below.

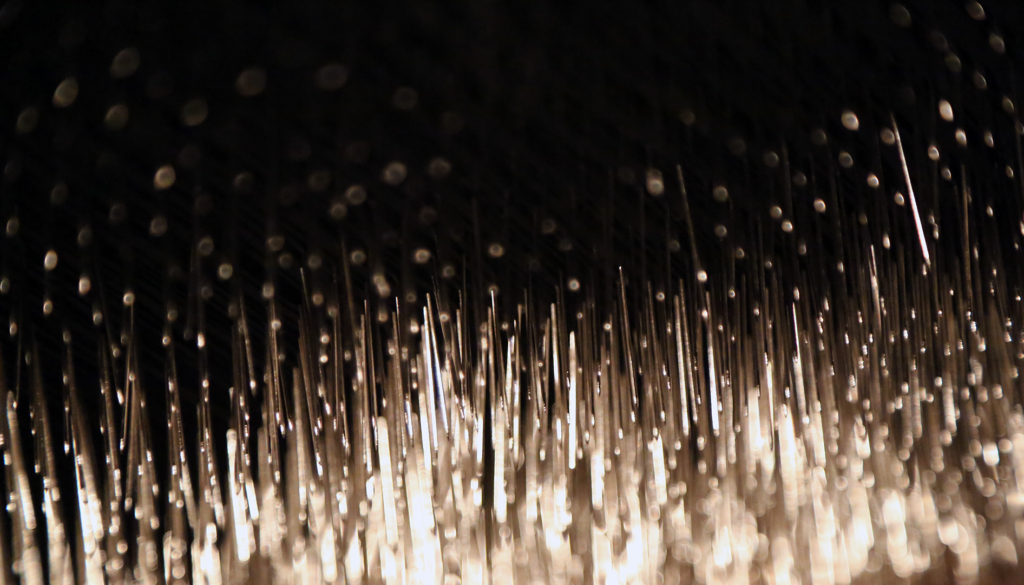

Natalia Gomez: Many of Sarika’s installations carry immediate visual impact, but this piece didn’t command my attention before entering the space. But then, walking into the enclosure, there was a weird, physical shift where you become aware that all of the pieces change as the light interacts with the nails.

David Bernabo: It was great to see a few glimpses of the pins from the outside and then once you’re inside, you turn right and there’s this dense field of silver. It reminds me of the [Hall of Minerals and Gems] at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

NG: Yeah, but with pins pointed right at you.

NG: With the pins shifting between line patterns to surface density, it is a fun way to draw the viewer around the room. But I do gravitate to the pieces where I don’t identify an observable pattern, because then I’m more focused on myself moving around the pieces instead of identifying the connotations of patterns like circles.

DB: There’s a central light within the enclosure, and it’s always in my field of vision. I keep trying to avoid it and, by avoiding it, I look around more. It’s a bit of an annoyance.

NG: Yeah, it has that noon-sun-on-your-head quality where I’m constantly furrowing my brow.

DB: But in that, it creates a tension that is mirrored with all these pins pointing at you. I’m not sure if that’s intentional, but the light is a constant presence in the way that the nails and the perceived pain would be inescapable.

NG: For me, the lights draw my attention to the physical space. There are four other lights shining onto the wall around the perimeter of the room. I wish that my visual field was a little more obscured. I’m too aware that there is a nice, clean corridor for me to walk around, but at the same time, the lights do invite me to walk around the corridor.

DB: So, the back of the paper provides a reveal to the origin of the patterns.

NG: Immediately, we see the design and the organization of these pins. I do think it’s fun to see the artist’s process. Some of these pieces are more line-based; some are more representational drawings of landscape, trees, organic growths. And then things get more abstracted. It’s an interesting contrast to have the physical, inside experience of these nails sticking at you and then stepping to the safe side, the process side, the more representational side.

DB: But the safe side is more like, “This is interesting.” I tend to prefer the bodily reaction of the pins, and the threat.

NG: Yeah, there is the physical, spatial, and then there is the object. I think I could appreciate the piece more [were it just] the inside. But there’s a fun moment where you [recognize the artist] put so much work into a piece, and there’s the artist’s pride, like, “look how cool this is, too,” and you want to get the most out of your work. Basically, these are two totally different pieces, and both sides are beautiful on their own. But in terms of space-making and having that physical shift for the viewer, the outside brings you back to reality in a very concrete way that may hamper the overall piece.

NG: We have black paper, hung in front of black walls, with thousands of tiny, tiny pins sticking out. There’s such an opportunity for your perception to shift. It would be fun to play with that darkness, like, how can you really make someone feel nauseous and uncomfortable?

DB: I could see this piece installed over and over again in different spaces.

NG: Because of its modular nature, there is really great potential to play with physical senses. I’m trying to think of the weirdest space to install it—what if you are in a park and you just encountered this rectangular enclosure?

DB: I could see this as an experiential theater piece. I’m thinking of Bricolage’s STRATA, where you enter different rooms to see different tailored performances. Goulatia’s piece is essentially creating an event where your performance dictates what you get out of it.

NG: Yeah, your behavior and how you move through this space are going to completely change what you see and what you feel. That’s one of the best parts, building the curiosity and moving around the panels because you saw the glimmer and the shadows. That process is a great evolution. And even though this rectangular enclosure is static, the viewer activates the space.

Sarika Goulatia’s exhibition Dressed with D.R.E.S.S. at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts runs through October 30, 2016.