Much of today’s discussion on local art centers on a few topics: sustaining a living as a Pittsburgh-based artist, creating equity in opportunity, energizing a local art market, or fostering critique. Studio Visit is a series intending to contribute to this discussion by spending time in-studio with artists, their work, and their thoughts on a creative life.

![]()

When her studio’s garage door is open, Sarika Goulatia’s work spills out of its confines, flooding the hallway of the former mine safety building with her artwork, gigantic structures like rough, pock-marked spheres, hole-filled planks of wood, a panoply of recycled and found objects bolted together and coated in white paint, like the dozens of shoeboxes that cover two walls from floor to ceiling. A grid of factory windows lets in bright, airy light.

I step into her studio, and we are off and running, jumping from piece to piece, series to series, discussing the personal narratives that tie her work together.

“In 2012, I had a drug reaction to sulfa,” Goulatia tells me. “I saw a rheumatologist because I have bilateral tendonitis thanks to the craziness in the way I work—I’m compulsive and I don’t take breaks.” (I would think back to this statement when later I came across work that consisted of 15,000 nails painstakingly hammered into wooden boards).

“So I went to this doctor and she prescribed a low dose of sulfa. I said, ‘I get a reaction with sulfa ointments,’ and even though the pharmacy advised her not to, she decided to give me a low dose. And I didn’t tell my PCP or my husband, who is a physician, because I thought they would tell me, ‘What’s the point?’ But little did I know that they had valid reasons.”

“But, long story short, I had a little bit of a rash and a high fever. I went to the hospital. They gave me steroids and sent me back. And by Monday, the rash was all over. I think I looked like a man. It was funny—whoever would walk in the hospital room would think they were in the wrong place. It was like seeing my funeral. Whoever would visit would sit there and cry in front of me. I was so weird to look at, it was disturbing to most people.”

Recently awarded the 2016 Emerging Artist of the Year distinction by the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts (PCA), Goulatia is preparing several rooms of work based on her experiences with her temporary physical transformation.

“On the corridor [of the PCA], I was going to do this mylar thing with mirrors going everywhere. The whole idea was that every time you walk into the room, you are confronted by your own face. For me and my children, my physical face was very disturbing. They kept asking, ‘Are you our mother? You talk like her. You wear her clothes. Are you our mom?'”

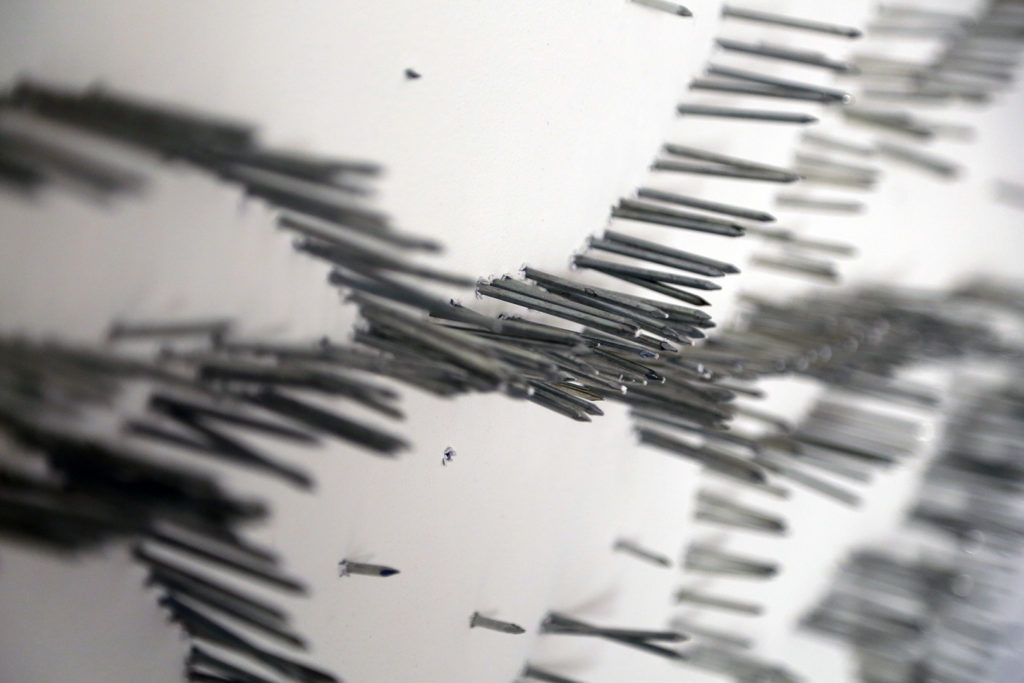

Much of the work spread around the studio contrasts objects of pain and threat—nails, mainly—with beautiful patterns. “Most of these patterns are from neurons,” says Goulatia, who told me that she was prescribed neuropathy medications to counteract the adverse physical effects.

Instead of new, store-bought nails, Goulatia told me, “I was going to use all of these rusted nails. But it wasn’t working for this show. I pinpointed the issue: Everything in the show is so white and silver. The [artworks featuring new nails] look soft, but threatening; but the rusted nails, they looked too harsh, and they created a different vibe.”

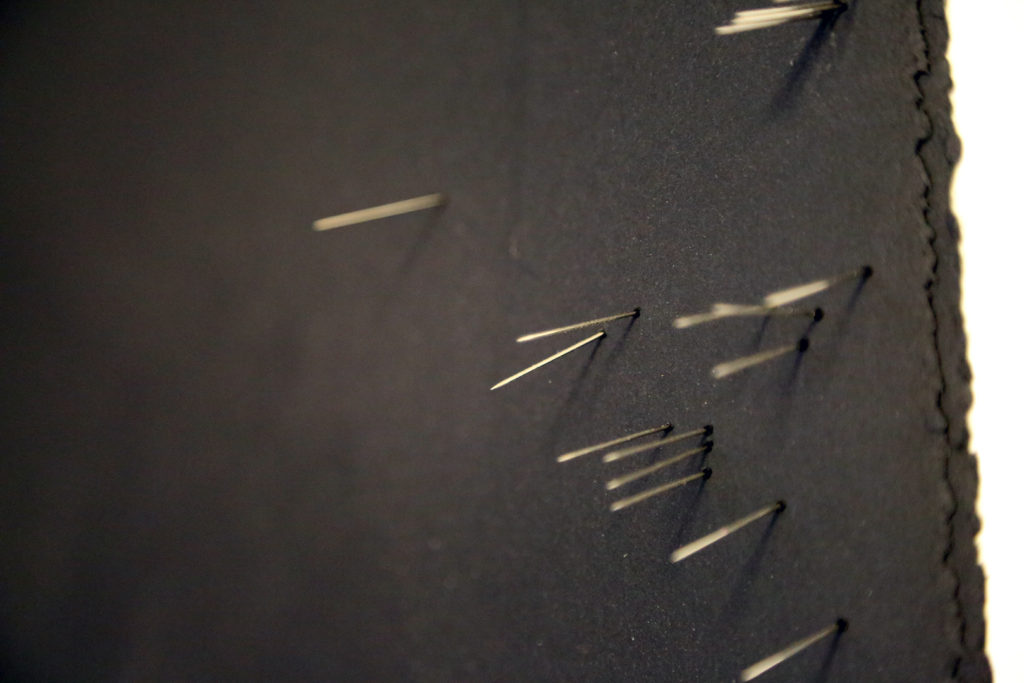

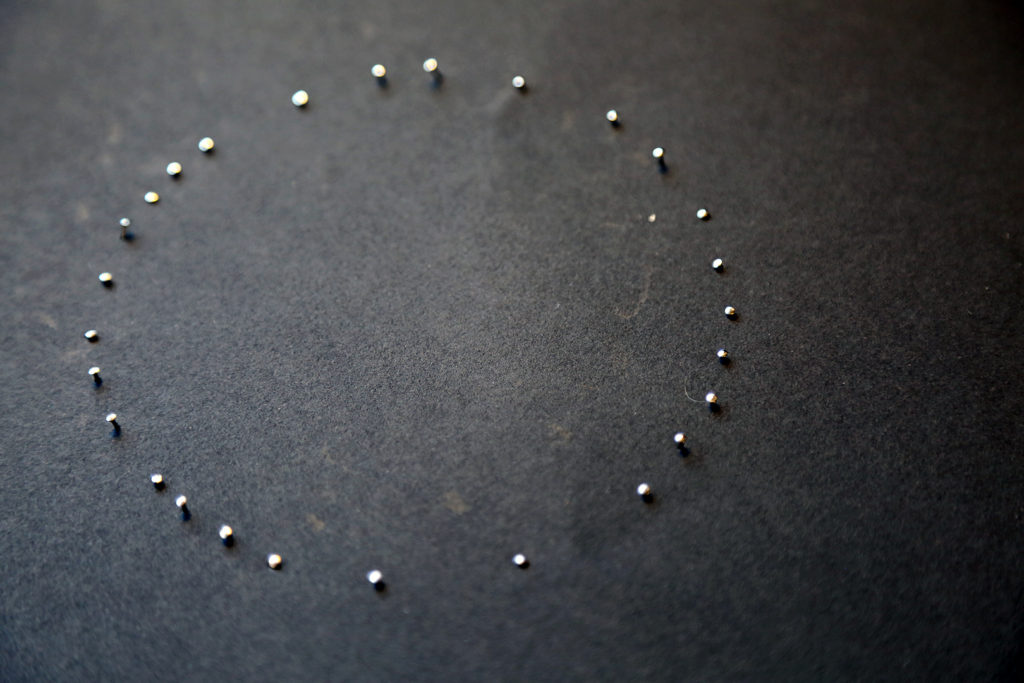

Another series, in which Goulatia used pieces of black paper, feels more subtle. “These pieces are going to be hung in such a way that you can walk around them,” she remarks. “But the pins are not painted black. The pins are steel. Look at the way the paper absorbs it. I like how it doesn’t look threatening, but it is.”

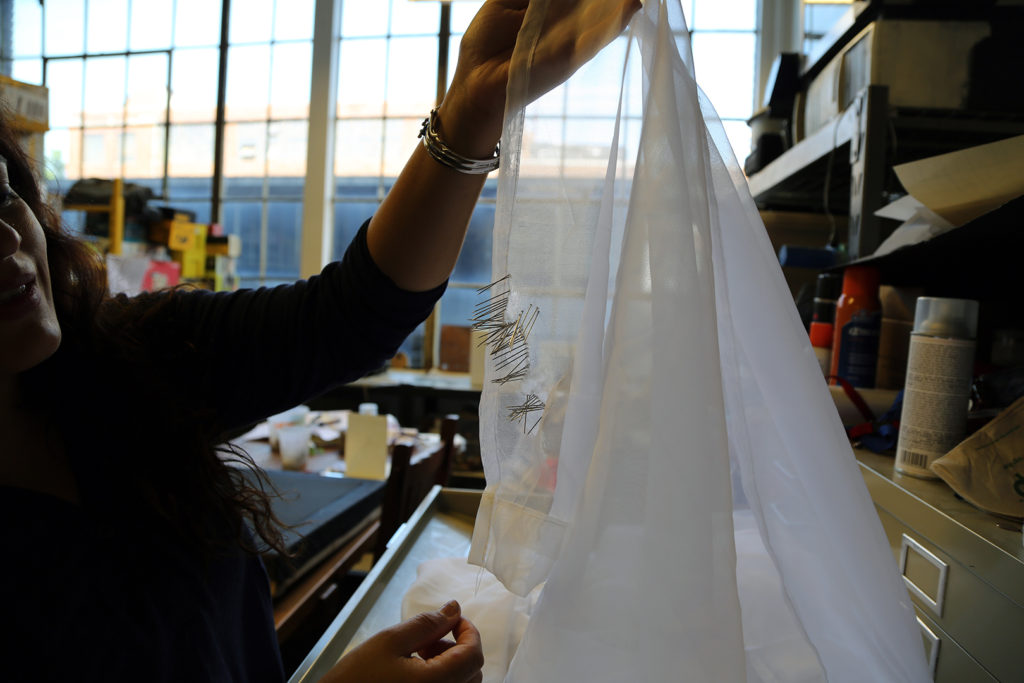

“Then for the room next to it, I am doing these sheer curtains. Some places you can see the pins, some places you can’t.”

“Then for the room next to it, I am doing these sheer curtains. Some places you can see the pins, some places you can’t.”

For her 2009 Mappings, Goulatia used different sizes of nails to map the deaths of the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks. In other work, she recontextualizes wood, removing the utility of a panel or plank and, sometimes, their structural integrity. With so much of her output incorporating these kinds of construction materials, she jokes that her studio is “a mix of an art and a hardware practice”—though these functionally ordinary tools are relatively new mediums for Goulatia.

“In India, if you want a painting hung, a carpenter comes and hangs it for you. Not only [for] me, as a woman, but also men. You don’t do anything, because there are always people to do [a job], because people need work. So, when I go to Home Depot and walk down the aisles, the objects—their functionality does not jump out at me. I don’t know what these things are. I think, ‘This would be great to do this kind of thing.’ It’s a different approach to the hardware store.”

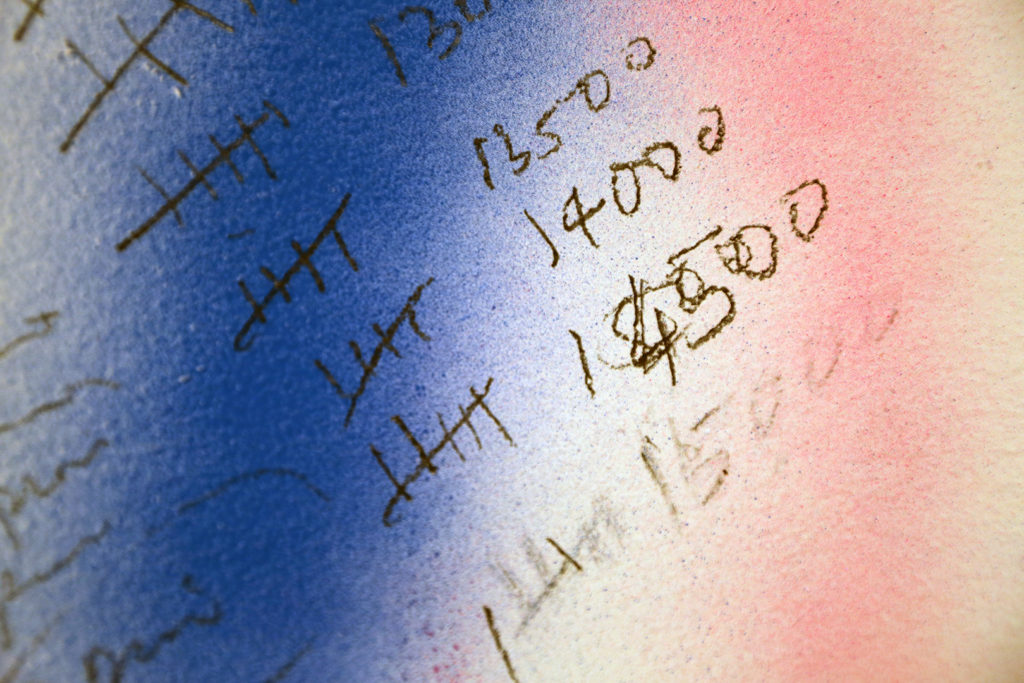

A nearby wall sports a hand-written tally indicating that 15,000 nails have been used so far. Whereas an abstract painting can be said to take two hours or two months to complete, depending on an artist’s process, Goulatia’s work can be measured by each nail hammered, pin inserted, shoebox affixed. The effect for the viewer is an inability to avoid mentally sifting through the labor involved.

A nearby wall sports a hand-written tally indicating that 15,000 nails have been used so far. Whereas an abstract painting can be said to take two hours or two months to complete, depending on an artist’s process, Goulatia’s work can be measured by each nail hammered, pin inserted, shoebox affixed. The effect for the viewer is an inability to avoid mentally sifting through the labor involved.

“I’m such a process-based artist that, if there is no process in it, it doesn’t feel like work,” Goulatia says as she continues sticking steel pins through black paper. “It’s a battle I’m fighting with myself. If I do something quick, I don’t validate it, which is sad. [She laughs]. I have to let it go, but then I question, ‘Am I being lazy or am I done?'”