Named after a local, early-1900s amusement park, Wilkinsburg’s Dream City Art walk returns for its second year on Saturday, July 16th. The five-hour event invites visitors to Wilkinsburg for live music performances, flash fiction readings, and a constellation of open artists’ studios. One participant is artist Carin Mincemoyer, whose work will be on display at 321 Pennwood Avenue. We caught up with Mincemoyer for a conversation about our perception and use of nature, simplifying and iconifying complex systems, and how her project for Dream City hopes to bring to light different perceptions of Wilkinsburg.

![]()

David Bernabo: Can you talk about your studio practice? Is it project-based or more of a consistent work schedule?

Carin Mincemoyer: It tends to be project-based. For many years, I was always working toward a deadline. It was always a show that has a theme, or it was a project that had a deadline. So there was a very specific type of project that [the work] had to be, there was a place where it was going to go, and there was a deadline by which it had to be done.

I just got really used to working that way. But I got tired of it, and I got burned out on trying to have a full-time job and do art projects for deadlines. So I stopped taking on shows for a while and just wanted to work with no deadlines or parameters to see what what I would come up with on my own. And it was really hard to make that shift, because when you can make anything you want and take however long you want doing it, it’s really hard to get motivated and have a very disciplined practice. Also, if you’re not already carried into a show that has some sort of the theme, you have to pick your own direction. For a while, I thought I needed to make a schedule and keep to the schedule, and I just haven’t been able to do it. I did end up with another deadline again. That’s what kept me focused and kept me working. Unfortunately, it seems like I need to have a deadline.

DB: Did your work surrounding concepts of “nature” come from that deadline-free time? Or has that theme been present for a while?

CM: For a really long time, my work has been driven by our relationship with nature and the natural environment and the different things that we want from that—the contradictory expectations and desires that we have of the natural environment. On one hand, we like to think of nature as this pure, unspoiled place where we can go and reconnect with the origins of our existence. But then on the other hand, we like to harness natural resources to make our lives more convenient. We pave roads so that we can get places quickly. We build shopping malls. We like to experience nature from the seat of a car—with air conditioning. So there’s a push and pull between do we like [nature] to be unspoiled or do we like being comfortable. [My work] addresses a balance between those two things.

DB: Most of your work that I’ve seen has been public art, like the daffodils—

CM: Dandelions. [Laughs]. It’s interesting that no one can remember what they are. People say, “Daffodils, flowers.” I need to somehow make that more more obvious, but it is very important that they are dandelions. [The piece] highlights these unsung heroes in our midst. Because dandelions are a pioneer species.

DB: Pioneers?

CM: Yeah, dandelions will grow where nothing else will grow, right? They’ll come up in a crack in the sidewalk if they can find one. They will send their taproot down into the hard dirt, loosen it up, and bring nutrients up to the surface. Then eventually other plants can move in and colonize the area. So, they’re the pioneers.

DB: Does the opportunity for a public art opportunity influence what you create?

CM: Typically, when there is a public art opportunity, there’s a specific reason why they are doing a public art project, and it’s never because they love art. There’s always an ulterior motive, right? There’s always some kind of goal that they’re trying to achieve. So you kind of have to design toward that goal. Public art is really more of a design process than it is an art process, because the sponsoring agency is trying to improve the walkability of their Main Street, or they want a landmark piece for their Town Square, or they’re trying to make their shopping district more distinctive and appealing. Then there are always practical considerations that you have to meet as well: There’s a specific space where they want it to go, or it needs to incorporate lighting. It’s a really different process than doing studio and gallery-based stuff.

DB: How do you handle the size and durability of public art? Can you make most of the work yourself or do you need to have certain pieces manufactured?

CM: With the smaller size work like [the lightning bolt and cloud] bike racks, I’ve done the work at TechShop, but there’s also metal shops where you can send them files and have them laser cut or waterjet pieces for you. Maybe you complete the finish work. For the dandelions, I [cut the shapes] at TechShop on the waterjet. Then, I painted them in the studio.

DB: Can you talk about your goals with the augmented tree pieces?

CM: I’m starting to think of them in a similar way to constellations—that is, about our need to find some sort of pattern or shape or organization, some sort of recognizable image in seeming randomness. It is about the search for pattern and shape and the need to find control in chaos. I did start out thinking that they would have more architectural forms in them, but they’ve since become more pared-down to the simpler geometric shapes. It’s really just driven by what is there, looking at the shapes of the branch, and imagining what sort of constellation would be formed by that branch.

DB: Is there a lot of trial and error regarding the positioning of the added material?

CM: There’s some of that, but there’s not really a specific, right answer. I think there’s also an element of labor in there, because I’m actually carving the entire surface of the branch. There are thousands of little knife marks on the surface of every one of those branches. Being able to see that is really important. There’s also this idea of applying labor and work to harness the chaos and make order out of it. And somehow improve upon what nature has just handed us. We can’t just take it as it is. We’ve got to work on it and make it better.

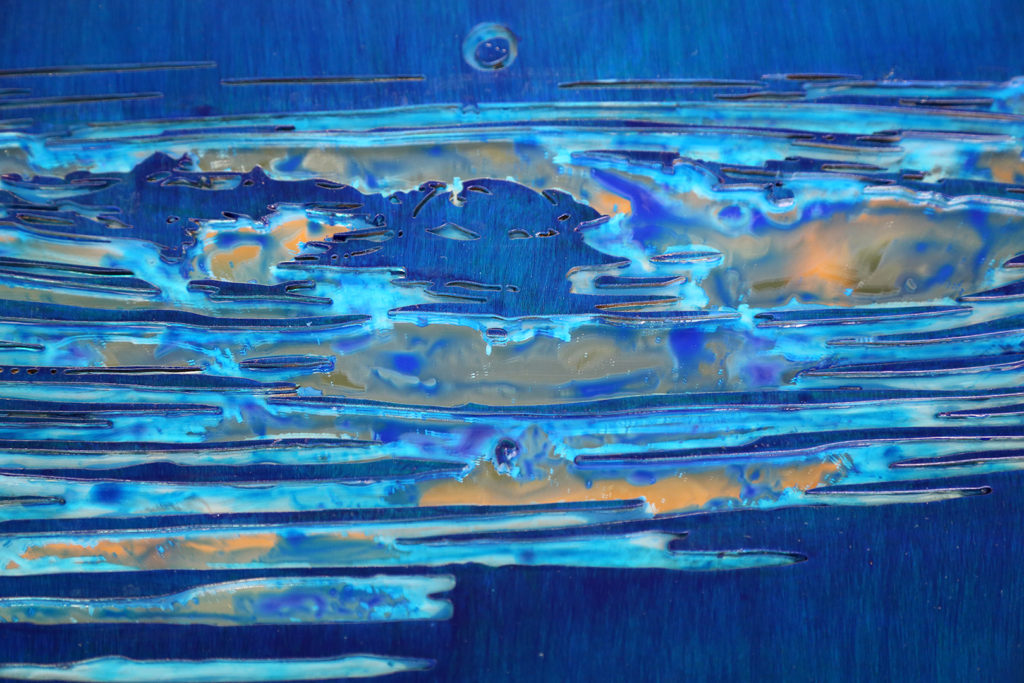

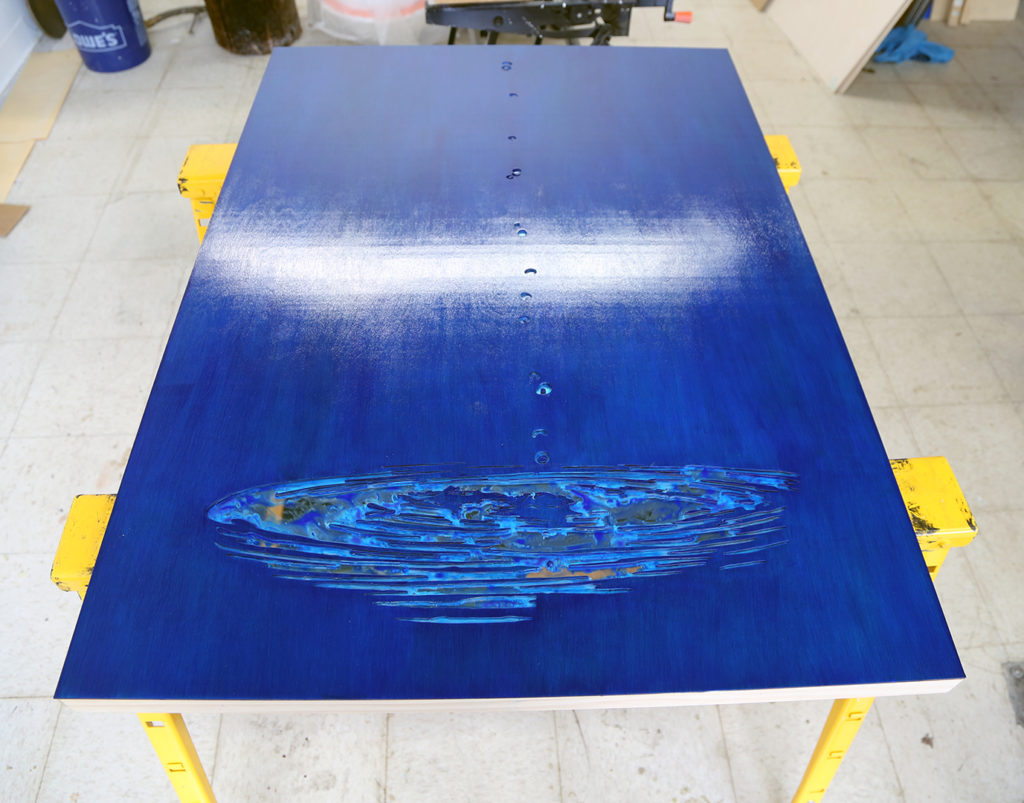

DB: Can you tell me about these water pieces?

CM: These panels are a series that I’m calling Aqua Icons. I was thinking about how we look at icons and logos and very simplified shapes that are supposed to represent more complex ideas. The bike rack that I did downtown—the lightning cloud symbol—was based on a weather symbol from a weather map. Obviously, a lightning storm is a lot more complex than that shape. So, I was thinking about water and how that can take many forms and obviously doesn’t have a shape. But we have an image of water ripples. What’s the perfect water ripple? If you’re going to look for an image or a clipart image of a water splash, what’s the perfect splash shape?

CM: These are backed by mirror. So, those are drops. This is the splash. Here’s a ripple.

CM: On the first couple, the painting part went really fast, but these are taking much longer to get the paint surface the way I want, because I’m not a painter. I have to figure out how to get something that I want when I’m not really sure what it is that I want. So you just keep putting paint on until you decide that you’re done.

DB: What was the draw of Wilkinsburg?

CM: Well, I actually lived in Wilkinsburg when I met [partner and installation/sound artist] Keny [Marshall]. I had lived in the East End and in Wilkinsburg for quite a few years at that point and I really loved it, because it was so green. There are lots of trees, people are out walking their dogs, you can walk to Frick Park. The neighborhood just has a nice feel to it. Then when Keny and I got together, I moved into [South Side live-work studio space] The Brewhouse with him. We were there for 10 years.

The Brewhouse totally had its benefits, but in the Southside, there are no trees. It’s all concrete and sidewalks and no trees. We were living right across the street from the hospital with the emergency room so there would be sirens all the time. It was the intense city experience. When it came time to buy a house, I didn’t think we could afford to move [to the East End], but we found a place that we can afford [in Wilkinsburg] that’s right across the street from a park. We feel really lucky that we were able to find an awesome house.

DB: What are you going to present for Dream City?

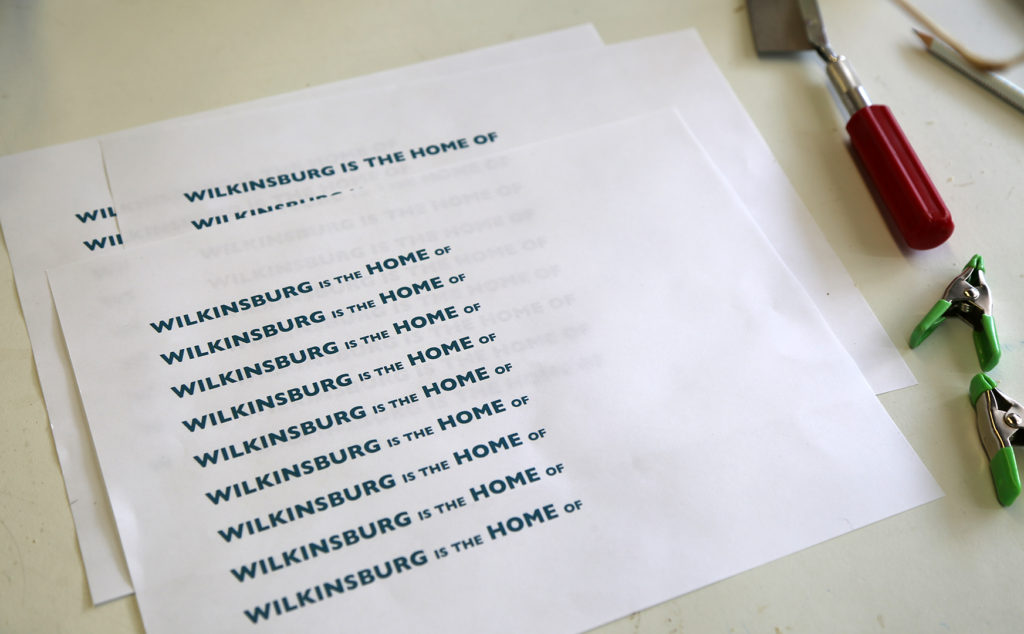

CM: I am going to do a participatory project that is based on public project that did not end up happening. The project was for a welcome sign for Wilkinsburg. As I was doing research for that project, I learned that Wilkinsburg was the only “Wilkinsburg” around as far as far as I can tell. So that’s kind of impressive.

The other thing I was thinking about was that when you have a transitional neighborhood like Wilkinsburg, everybody knows about the bad things that happen because that’s what makes the news, but most of the good things that are talked about are things that might happen in the future. So, crime and future opportunity are the two things that people think about when they look at transitional neighborhoods.

I think what gets skipped over is that people actually live here now. There are people living their lives, running businesses, making art, and going to school. So, what I’m going to do is have a big poster that says “Wilkinsburg is the home of ___,” and people can fill in the blank. You’ll see multiple answers to that question. I decided to add an extra layer to the project, [with] two ballot boxes for people to fill in the blank. If you’re from Wilkinsburg, your answer will go in one box. If you’re from outside Wilkinsburg, your answer will go in another box. Once I print those answers out and post them on the wall, you will get to compare and contrast and see if there’s a distinctive difference between people’s perceptions that live in the borough versus people’s perceptions that live outside the borough.

![]()

Carin Mincemoyer will be participating in the Dream City Art tour in a pop-up exhibit at 321 Pennwood Avenue. Visit here for more information.