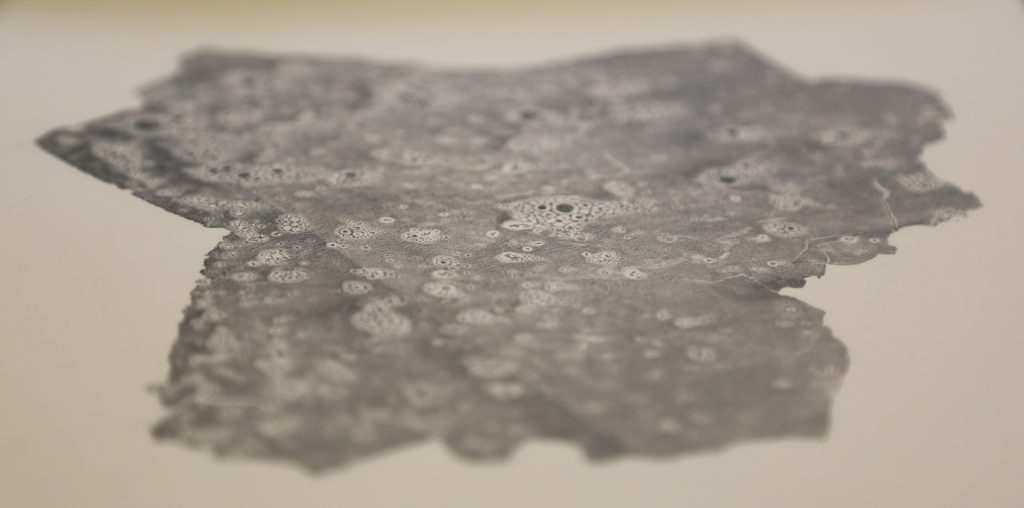

Named after a local, early-1900s amusement park, Wilkinsburg’s Dream City Art walk returns for its second year on Saturday, July 16th. The five-hour event invites visitors to Wilkinsburg for live music performances, flash fiction readings, and a constellation of open artists’ studios. One participant is artist Haylee Ebersole, whose work will be on display at Joab Naylor Studio at 1200 Hill Avenue. We caught up with Ebersole for a conversation about the process to create her highly-textured, dehydrated gelatin sculptures. Recently, Ebersole has experimented with translating these mutating gelatin shapes to the flat surfaces of an ink print on paper. The prints retain much of the detail and texture of the sculptural work, but are flattened from 3-D objects to 2-D depictions.

![]()

DB: The first time I ever saw gelatin as an artmaking tool was with your work, and I was curious if this was something that other people are doing or if you stumbled upon it somewhere.

HE: The only thing that I’m aware of, which is kind of what influenced it, is the leaf gelatin that they use in baking. It comes in a dehydrated sheet. Sometimes it has a design, and that’s what allows them to make off these crazy forms with cakes. But I had started using gelatin in its jiggly form with video work that didn’t really work out. I was interested in it because it mimicked qualities of the human body. I was trying to draw comparisons between the two, especially since gelatin is made up of body.

DB: Is gelatin animal fat?

HE: It’s really kind of morbid. It’s connective tissue, it’s bones, it’s ligaments. All of that is boiled and goes through all of these distilling processes which make the final material that is mostly made up of collagen, which is what our hair and our nails are made of.

HE: I thought it was an interesting material to use. I actually got lazy one day and didn’t clean out the bucket I was using and came back a few days later and realized that the gelatin dehydrated and left this shell inside the bucket that was an exact replica of it, but a variation as well. So that’s how it started. From there, I started using it in larger quantities. I bought 100 pounds of gelatin four years ago, and everyone thought I was a little crazy. It showed up on my doorstep in this huge drum. By talking to folks at the manufacturing facility, they helped clue me into the material qualities and the chemistry of what was going on. I realized that once it dries out, I can hydrate it again with water, and it’ll get gelatinous again. And if I heat it back to the natural resting temperature of the animal it came from, it’ll melt back into a liquid. So some of these [sculptures] have been melted down already and cast out into different forms. I’m using that same quantity of gelatin over and over again.

DB: Is that helpful if you don’t sell pieces from a show and you don’t want them around?

HE: Yes, very much so. I’ve been selling a little bit of work recently and it’s kind of an interesting predicament to have because it’s a material that I don’t really know the longevity of and I don’t know how it’s going to last over time. I have been telling people that if it breaks down or something happens to it, give it back to me and I’ll melt it down and cast it into something new for you. I’ve found that I really like cycles, there’s all this life and death that happens with the work.

DB: So is the dehydration just the natural heat in a room or do you put heaters?

HE: It’s mostly just airflow. The less humid, the better, and a lot of fans. Actually, when I first started working with the gelatin all my studiomates in grad school were really not happy about it, because it smelled bad. But now I’ve been using different additives like borax to mix with the gelatin to keep mold or bacteria from growing. It will also make it crystallized.

DB: Do you know if the material that goes into making the gelatin is a byproduct of food production?

HE: That brings up a really good point, which is one that no one has really called me out on the ethics of using this material before. I don’t want to be supporting an industry that’s not good, but as far as I know, it’s largely a byproduct of the meat industry, and I don’t think animals are being groomed particularly for this—at least I hope not. But the place that I bought my gelatin from, they manufacture gelatin in all different formats: gel capsules for medication, photography, food industry, so many other different applications. It’s crazy how this material is in every part of our everyday life in so many ways.

DB: I’m guessing your three to six shows a year aren’t breaking the system then?

HE: I hope not. I think I’ve kind of justified it a little bit for myself in that I’ve been able to reuse the material that I have. I like that it’s this reconstitution, [bringing] it back to this once living animal.

I haven’t really wrapped my brain around this yet, but a lot of the forms that I use and the colors that I use are derived from looking at Ikea catalogs and dollar store advertisements and taking this industry of mass produced objects and using gelatin to draw from that in some way, which maybe talks about its context as a material.

DB: Is that because of the shape? Does it have to adhere to a certain shape to dehydrate?

HE: It has to be held in something. Like this one [she points to a small, bluish sculpture] is kind of like that where I’m just using plastic sheeting to make a trough or a mold and pouring the gelatin in and letting it dry out.

I like working more spontaneously or intuitively where I’m just pouring blobs out here and there. But one of the things I always go back to is casting the gelatin in plastic bins or manufactured objects. You can really tell the agency of the material, the way [the material] adheres to [the object], the ways that it rebels against it.

DB: How do you judge what you like with so little control after sculpture is cast?

HE: It’s a great exercise in letting go of control. Sometimes I keep the things that I don’t like the most just because it’s honoring the material in some way. I’ve developed a more intimate relationship with the gelatin in that way. I feel like [in] a lot of my work, maybe one piece doesn’t necessarily stand alone by itself, but it’s a collection of different objects and things that go together, and that’s when they’re finalized. I love the ability to rearrange objects and see how they differ or what similarities are made visible by putting different things together. Often I’m not really thinking of that when I’m making things; I really try to let go and be intuitive and spontaneous, and then it’s afterwards that I’m kind of curating through things and there’re just happy accidents.

DB: How fragile are these?

HE: The larger ones are pretty resilient. They’ve fallen down a few times. I suppose they’re most vulnerable if it’s humid or windy. The pink one over there used to be totally flat—now it’s curled up in a different way just because of the humidity.

DB: How do you prepare for a show? Have you gone through different styles or periods with casting?

HE: I’m always trying to make new things, and I will just clear out my studio and make it more of a laboratory. I try to bring in as many different materials as I can and experiment until the very end. I don’t think I really ever wrap my head around anything being finished, especially since there’s always that possibility that the sculpture could be melted down and transformed into something new. It’s mostly just having fun and doing a lot of different material studies that I curate down at the last minute.

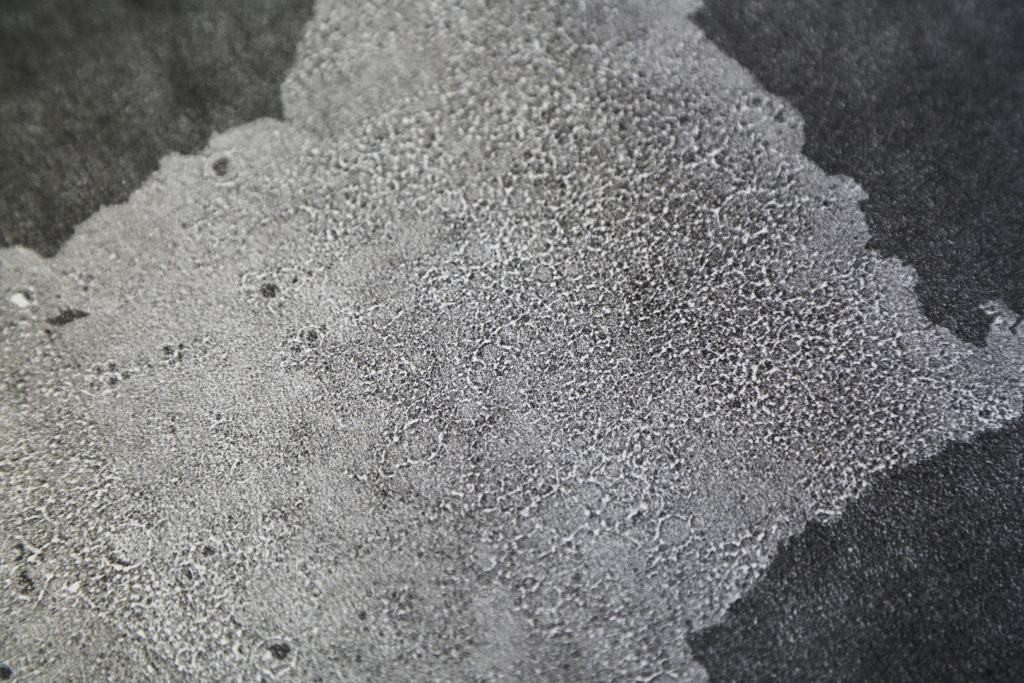

DB: Can you tell me about these new prints?

HE: I haven’t really been doing any kind of traditional printmaking, other than at my job as a letterpress printer. I went to Vermont Studio Center a few weeks ago for a printmaking residency, and it forced me to get back into it. So I’ve been doing a lot of monotypes that I’m using gelatin as the matrix to print from. All of these are studies that are trying to relate the sculptural work to the two-dimensional prints and find similarities between the textures. I guess it’s just a different way of understanding what that material is.

DB: Your degree is in printmaking, right?

HE: It is in printmaking. When I went to grad school, I started primarily working with gelatin in a sculptural way and I realized that I’ve been more influenced by the idea of the multiple rather than any kind of traditional printmaking technique. So a lot of the gelatin work is cast from the same mold but then the results are all of these variations in their forms and colors. I love seeing the material rebel in those ways, that it never really adheres to the boundaries of the cast.

DB: What was the inspiration for the prints?

HE: When I first started this series I was thinking about it as an archive or a way to document particular sculpture before they die and are recast in a different form. So it was taking some of the fragments from those different sculptures, inking them up, and using them as the matrix to print. I was doing primarily just black and white and one on a page, kind of thinking about them like photographs. But I realized it wasn’t really that interesting, so I loosened up. So now it’s really more about the surface material. It’s interesting how they go between feeling map-like from an aerial view, to a little bit of sunburnt skin or something. I’ve always strived for that dynamic between the grotesque and the beautiful.

DB: Do you feel like there’s more pressure in that you can’t remake the prints?

HE: Yeah, I guess so. But working in monotype, it allows a freedom where there’s still that push and pull between the material. There are things that I can’t necessarily anticipate happening, which I guess drives me. I’m still thinking through the prints, but I’m interested to see what would happen if they were used as substrates for sculptures to sit on or interact with. Maybe they aren’t presented in singular traditional prints but they come into play in a different way.

DB: Since the gelatin pieces take so much time to dehydrate and mutate, a studio space seems pretty essential. What drew you to Wilkinsburg as a place to live and create?

HE: I have to give credit to my awesome friends who live here. I met a lot of the artists who live in Wilkinsburg in grad school at Ohio University. They all started out doing some really amazing work, making their own studios, opening up a small shop, opening up [Brandon Boan’s linotype and letterpress print shop] Tip Type. There’s that draw that you can buy something here or live here for cheap and be able to be an artist and not have to work full time. I also really wanted to live somewhere where I was exposed to and could contribute to an environment that was diverse. I really love my neighbors. We have a great time together, and there’s this really great sense of community here where people are coming over and asking if they can borrow a cup of sugar.