Artist, curator, and writer Elena Harvey Collins recently spent time in Pittsburgh as the second participant of Casey Droege’s The Residence, supported by the Mattress Factory and Radiant Hall. During her residency, she met with several artists, including Tina Williams Brewer, to explore their practices and interactions with the changing landscape of Pittsburgh. Brewer is an internationally-renowned artist who uses the form of story quilts to explore African American history, symbolism, and issues of women, family and spirituality. Her work has been exhibited around the country, including in the Tampa Museum of Art, Huntington Museum of Art, and the African American Museum in Philadelphia and Dallas. This is the first in a series of essays to be released across several online platforms.

![]()

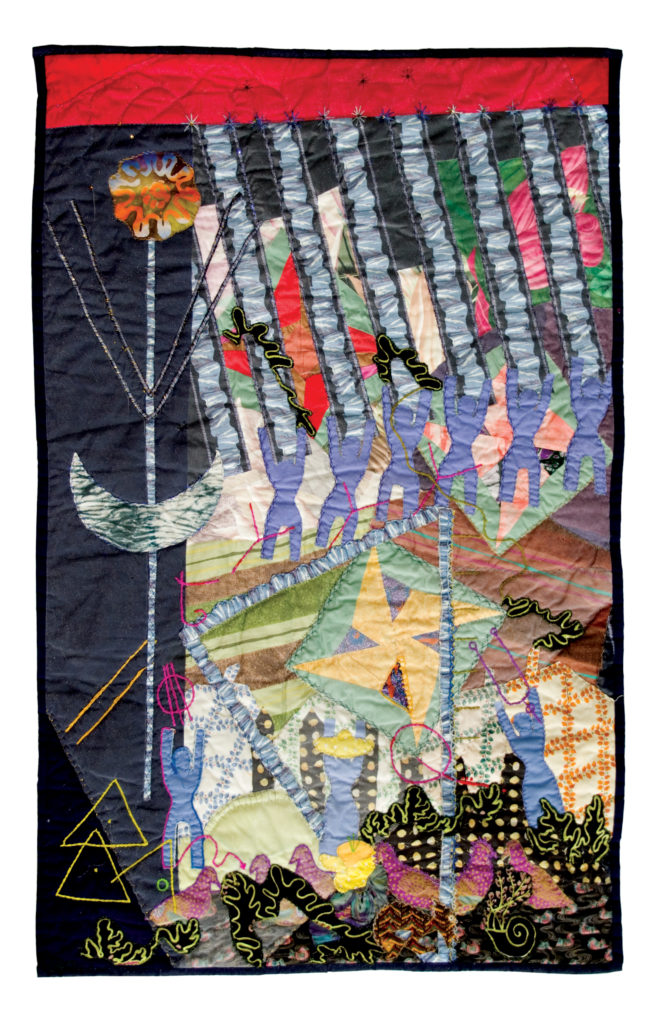

The form of a thicket is a good way to start thinking about Tina Brewer’s work. A site of entanglement, refuge; each twig a strand of raw data. In Rising from the Thicket (2014), multi-bodied human forms radiate outwards from a strip of camouflage fabric. Signaled by the hunter’s disguise, the thicket is where both the hunted and hunter reside. So it’s not safe exactly, but it is intimate.

Quilts move simply and without fuss. They can be handled casually, with familiarity—slung, rolled, fluffed, shaken out: Brewer does all of these things as we lay her quilts out on the floor of the Pittsburgh Coliseum, the community space she operates with her husband, oral historian John Brewer. She moves from piece to piece, charting a personal journey of discovery and research into the cosmology and culture of the Akan and Dogon cultures of West Africa, among others, and African American history, begun after moving to Pittsburgh from West Virginia in 1971. From the thicket, we move with Brewer up and out through other intimate spaces: the slave ship, the safe house, the dance, to her current focus; the landscape of Pittsburgh. Brewer, who currently resides in Homewood, has lived here for over 35 years, “learning the city,” as she told me. Made up of a series of named hills (Spring, Squirrel, Troy), Pittsburgh has a particular verticality. Not the soaring, skyscraper kind, but the kind that makes thighs burn and breath short. Quiet, bright high streets; stacked, shale-backed homes; thick undergrowths of invasive ivy; short cuts; hilltop cemeteries: a certain insular and watchful quality that makes even long term residents feel strange sometimes.

Traditionally, quilts are constructed according to a set of predetermined patterns and conventions, a communal technology in which the means of expression don’t belong to any individual. Brewer moves between rejection and embrace of those constraints; sometimes they literally hold it all together, as with the Irish Chain pattern that unifies the surface of a recent work, #1 Of This Place (2016). One level below the chain, office-block forms, based on the disposable, Panera-souled architecture of the new Google campus in Larimer/East Liberty, are stitched over the existing landscape of Pittsburgh, imposing their rectangular authority. This work is the first in a series of quilts addressing the changes in the city, and the homogenizing forces of gentrification and displacement coursing through neighborhoods like East Liberty.

At other times, the unpracticed eye is confronted with a dense matrix, as in Whirling Dance and the Unconscious Rhythm (nd), in which ghost images, overstitched symbols, patterns and images form a multilayered code, which Samuel W. Black in 2009 noted “indicate a mathematical structure as well as a spiritual synthesis.” As with the experience of peering into a thicket, these quilt-codes can be hard to read. This is partly intentional, descended as they are from practical imaginaries of the pre-emancipation South, where symbols stitched upon a quilt, hung casually over a gatepost, or displayed in a safe house window, might direct runaways along the Underground Railroad, denoting where sustenance could be had or who could be trusted.

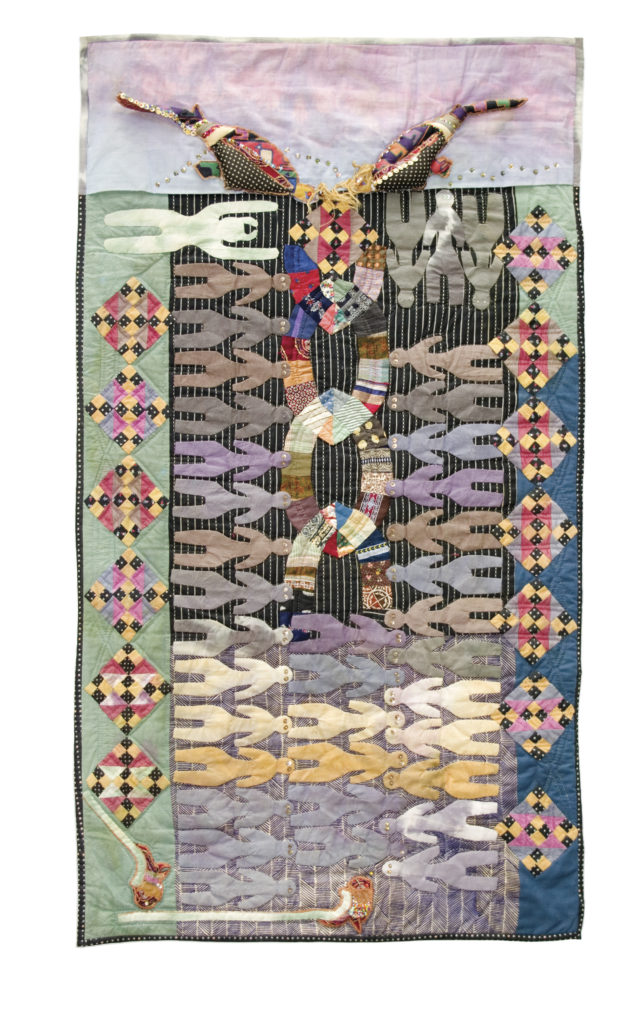

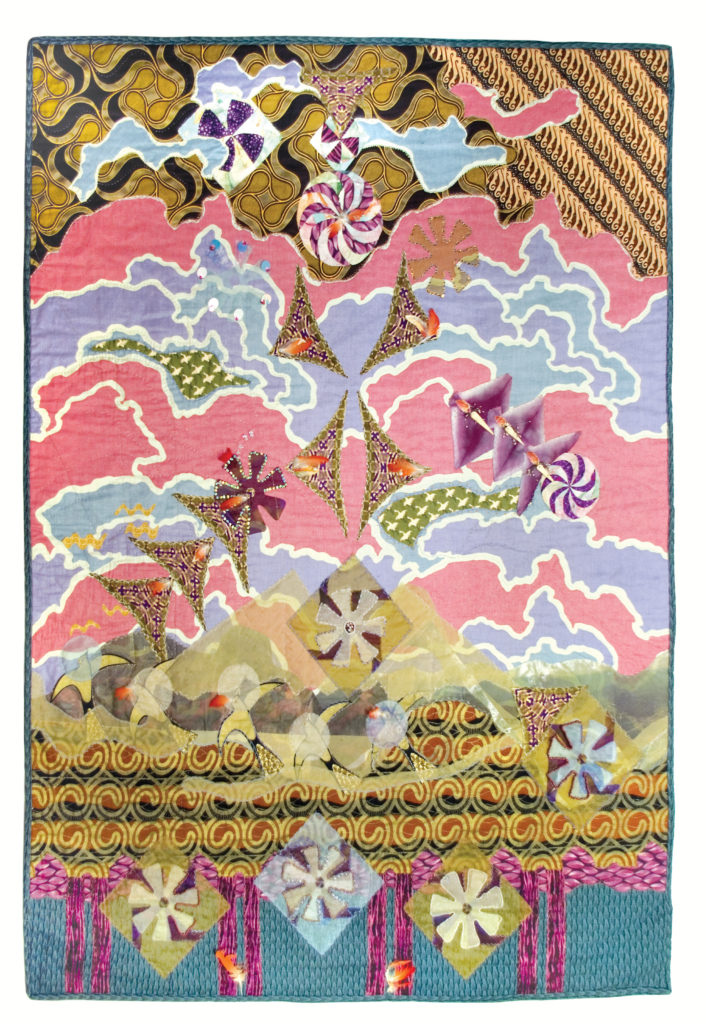

Something I have noticed in thinking about quilts is that quite often they don’t bother with dates, or, the date of completion spans a number of years, is imprecise, is labeled with “circa.” The quilt is never-finished, as the work can always be taken up again. Brewer has developed a syntax in which each scrap of fabric is a citation, a language with branches that stretch outwards and snag on the now—the repeated image of figures holding their hands up (The Harvest, 1989; Migration Blues, 1998) summons Ferguson; screen printed migration routes, graphic depictions of diasporic movement (Hand of God; Cosmic Endeavours, nd) connect to a sense of displacement, a key feature of early 21st century life, whether intra-city as in East Liberty or devastating on an international scale as in Syria. This quality of availability speaks to Brewer’s sense of time and perspective, as well as a connection to the deep grammar of life. As she says, “I see everything from the air.” Accordingly, the quilts operate not so much as objects but as open-ended maps plotting a route through histories of migration and trauma.

Through, and beyond: Another of her works is titled Formation (2002), a word impossible to read in 2016 without bringing to mind Beyoncé. In the quilt, colorful abstract forms swirl towards a central point of coalescence, as if a celestial body. For me, quilts always relate back to the human body, through their sense of scale and proportion. Even quilts that are only ever intended as art works, like Brewer’s, retain a relationship to collective use-memory, remaining bedspread- or baby blanket-sized. This potential to cover and enfold the body is powerful protection, summoning the feeling of childhood and the desire to hide: In an enclosed space the self-forming form can do the work of becoming itself. In this way, Brewer’s work is like speculation. Reconstituted Black cultural forms, icons, and material culture, refracted and fragmented through the prism of Diaspora, move steadily, insistently, towards the future.