The Guardian’s advocacy is a partnership with 350.org, an organization with branches all over the world—including in Pittsburgh, where last summer’s Climate Action Rally brought together a constellation of environmental groups and politicians to Allegheny Commons.

One of Pittsburgh’s leaders in this fight is Divest Pittsburgh, a project of the peace and social justice organization the Thomas Merton Center that took on the challenge of pushing the City of Pittsburgh to divest its substantial Municipal Pension Fund from fossil fuels.

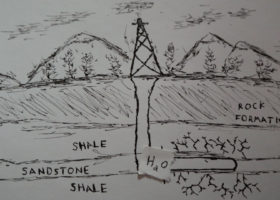

“[We’re] asking them to divest within the next five years,” Divest Pittsburgh member Wanda Guthrie said. “It’s not meant to make this huge impact on gas and oil. We know that won’t happen. What it is saying is we are not going to do business as usual. We have to leave this in the ground, because if we use all of the reserves, the planet will be unlivable.” A board member of the Thomas Merton Center, Guthrie helped draft the Municipal Divestment from Fossil Fuels Act in December of 2015 that was then sent to Mayor Peduto and City Council for consideration.

![]()

The Administration is listening. That same month, Mayor Peduto, who delivered the concluding remarks at last year’s Climate Action Rally, traveled to the Paris Climate Summit as part of the Compact of Mayors coalition. There, Peduto spoke about the role that cities must take to counteract climate change and then presented his proposal “for reducing … emissions through renewable energy consumption, energy and water conservation, fleet conversion, landfill diversion and transportation emissions reductions” by 2030. His plan also included the creation of “a fossil fuel divestment strategy for City of Pittsburgh funds.” And City Council President Bruce Kraus has signed on to do his part, assuring that his office will take up Divest Pittsburgh’s message and legislation—a move that the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Editorial Board brushed off in January as a “political statement” that “reflects a national fashion.”

Fashionable or not, a pension fund divestment would ultimately come under the purview of the City’s Pension Board, a panel made up of the Mayor and City Council President Kraus, plus City Controller Michael Lamb and employee representation. “To date,” Kraus confirmed, “the Pension Board has not taken any action” on divestment.

In conversation with Guthrie her fellow Divest Pittsburgh activists Kimmy Dinh and Gabriel McMorland, I learned more about the intricacies of the Pension Board and the way forward for divestment.

Kimmy Dinh: It’s not legal for City Council to directly tell the Pension Board to divest. So, now we are trying to get more support from members to have a resolution within the Pension Board.

Gabriel McMorland: The Pension Board has its own legal counsel. The legal opinion of the Pension Board’s solicitor, which we haven’t seen in writing, is that City Council cannot direct the Pension Board to divest. City Council can express opinions—they could sign a letter saying that we really hope you’ll think about this. But what we learned is that the official vote has to come from the Pension Board.

Wanda Guthrie: Which makes good sense. Councilpeople come and go. The Pension Board needs to cover employees. The problem with pension funds altogether is that they are looking at this as fiduciary responsibility, but we found that you can invest in other funds and find similar results. The National Methodist Church divested completely. So did the United Church of Christ.

Dinh: We want to make the case that divestment is the financially responsible thing to do. We want to make the case that the fossil fuel industry will not persist in the future. We want to ensure that people’s investments will not go bad. This is a strategy to pressure the industry to influence the economy, to put stigma on the fossil fuel industry, so that over time people will move into renewable energy.

McMorland: When hundreds of industries around the planet are pulling their money out, that creates a big amount of pressure on the industry. Part of what the industry relies on is using a large amount of media and political power to pass the real cost of their industry onto the people, public health, water, air.

The argument for divestment is a moral one in addition to a financial one. As climate change continues to prove its existence, changing weather patterns are expected to create ever-bolder storms and natural disasters, drastically alter food growth, and threaten the livability of certain lands.

Guthrie: A couple of years ago when Bill McKibben was here, he said, “We are running Genesis in reverse. We are de-creating.” I’m working with a Lenten eco-theology group. We talk about being in touch with the earth and remembering what creation is. We go back to how one nurtures everything around us. How do we relearn to nurture? The changes are going to be something that take a great deal of kindness and compassion for everything around us.

Dinh: Environmental justice is not just about the environment. It’s about people. Climate change harms communities and public health. There is so much displacement resulting from climate change. I can’t be a social justice advocate and not be a divestment advocate.

McMorland: We want to reduce the climate risk of the pension fund, but there are also moral reasons. Pittsburgh was actually the second city in the nation to divest from companies doing business in South Africa during apartheid.

With the roots of climate change being so global, so wrapped in fossil fuel corporations and nationalized drilling efforts, so tied to international trade policies, so ingrained in every product that we use—how does a person start to fight it? Divestment is one pathway.

Dinh: Divestment is a way to actively change what the economy is about. Different people have different viewpoints. I’m around a lot of engineering students. They look at climate change and they look at green building, because that is where they can address climate change—by building cities that are resilient to climate change. That is where it starts for them. But I don’t think that can happen without the push away from the fossil fuel industry. The two ideas can work together.

Guthrie: When we first started this campaign, we asked how will we phrase this. Well, we didn’t just want to talk about sustainability. We want to talk about thrivability. What makes Pittsburgh thrive. What makes the region thrive. How can we make those changes? How can we get people to dream about this? Personally, this is for the future. It’s for my grandchildren.

It’s a thing I see more and more. People are starting gardens and trying to make their community better. It’s a thing that gives us hope that we can really do this. We can change our lives. We can live more simply. We can give a little more so that others can simply live.

McMorland: It’s about collective action. We are not going to get ourselves out of this climate crisis by improving our own individual lifestyles. It is going to take collective action focused on the small group of organizations that hold most of the power over the climate crisis. The fossil fuel industry is one of the major players. No amount of buying the right light bulbs, taking shorter showers and growing my food is going to counteract the huge damage done by the industry.

During our discussion, I brought up my attempts to divest my own PNC Bank savings from bonds and mutual funds that include fossil fuel investments. Though PNC currently does not provide an easy option for personal divestment, most of PNC’s holdings include only 1-10% fossil fuel investments, because the industry is not viewed as a strong, long-term strategy. After I brought up PNC, our conversation turned to a decision last year that had environmentalists applauding.

McMorland: What is interesting is that PNC recently decided to no longer extend lines of credit to companies using mountaintop removal to retrieve the majority of their coal product. If more than 75% of your coal product comes from mountaintop removal, PNC will no longer extend a line of credit to your business. And those are some very large businesses. What is interesting is that the reason that happened was because of collective action. There was a several-year-long campaign led by Earth Quaker Team. They came together, held prayer circles in retail bank locations, brought giant photographs of mountaintop removal. They sang and they vigiled. PNC has a lot of retail customers, and they are worried about their brand. And they gave into the pressure and did the right thing. Now, PNC doesn’t have a brochure saying, “Hey, the Quakers told us to do the right thing and we did” after two years of people being arrested. But it is a really inspiring story. You can motivate a company to change the way they look at the world around them.

Guthrie: I was part of that. It was really inspiring. The Philadelphia Quakers actually walked across Pennsylvania, stopping at PNC banks everywhere, singing “This Little Light of Mine.” [And at each bank] they had one person divesting their money.

In December of 2015, it was announced that over five hundred institutions representing over $3.4 trillion have pledged to divest from fossil fuels. Some of the bigger institutions include Rockefeller Brothers Fund ($850 million portfolio), Allianz ($1.9 trillion portfolio, switching from coal to wind investments), University of Glasgow (reallocating ~$25 million), Guardian Media Group ($1.1 billion), and the World Council of Churches (representing 500 million Christians).

With more and more organizations joining the effort to divest from fossil fuels, it’s clear that this is a campaign with traction. And though the global climate outlook may be dire, the fight to counteract climate change is at its core a fight for equity—a worthwhile fight for Pittsburgh.

![]()

Divest Pittsburgh invites others, especially City employees, to join the campaign. To find out more, contact fossilfreepgh@gmail.com or visit their website or Facebook page.