Much of today’s discussion on local art centers on a few topics: sustaining a living as a Pittsburgh-based artist, creating equity in opportunity, energizing a local art market, or fostering critique. Studio Visit is a series intending to contribute to this discussion by spending time in-studio with artists, their work, and their thoughts on a creative life.

![]()

It is mid-February 2016, during a stretch of unseasonable warmth. I’m visiting Elizabeth Rudnick’s studio at Radiant Hall in Lawrenceville, where I find an assortment of paintings, netting, empty frames, and a wall full of images, text, and small works. At the time of this interview, Rudnick has work in two exhibits—her excellent solo show of abstract painting You’re Not Real, I’m Real at 707 Penn Gallery downtown, and in Houston, Texas at the Cindy Lisica Gallery, a series of over-painted vintage photographs in Over Time.

Elizabeth Rudnick: These are all brand new. [She’s pointing to the paintings scattered around the studio]. The studio got pretty emptied out for the show at 707 Penn Gallery, and what was left were the rejects and new projects. Not necessarily rejects, but they all need resolution. They’re part of the same series, the “When Did You Have It Last” series. It came out of digital anxiety but moved into painting, so they all have this choreographed but fast gesture, layering similar colors or monochrome on top of each other to add some angst, some hierarchical fight to the strokes.

Abstract painting is my first language and I’m figuring out how to describe contemporary fears and anxieties without using the media related to those fears and anxieties. Trying to use an analogue, trying to use paint.

It’s as much about my relationship with learning how to paint since that is a never-ending process. There’s been some reception by viewers, especially when I put the titles [with the paintings]. I’m trying to make this funny and try to use the title to that effect. This one is called “Minesweeper.”

David Bernabo: Are the marks improvised or do you sketch the shape beforehand?

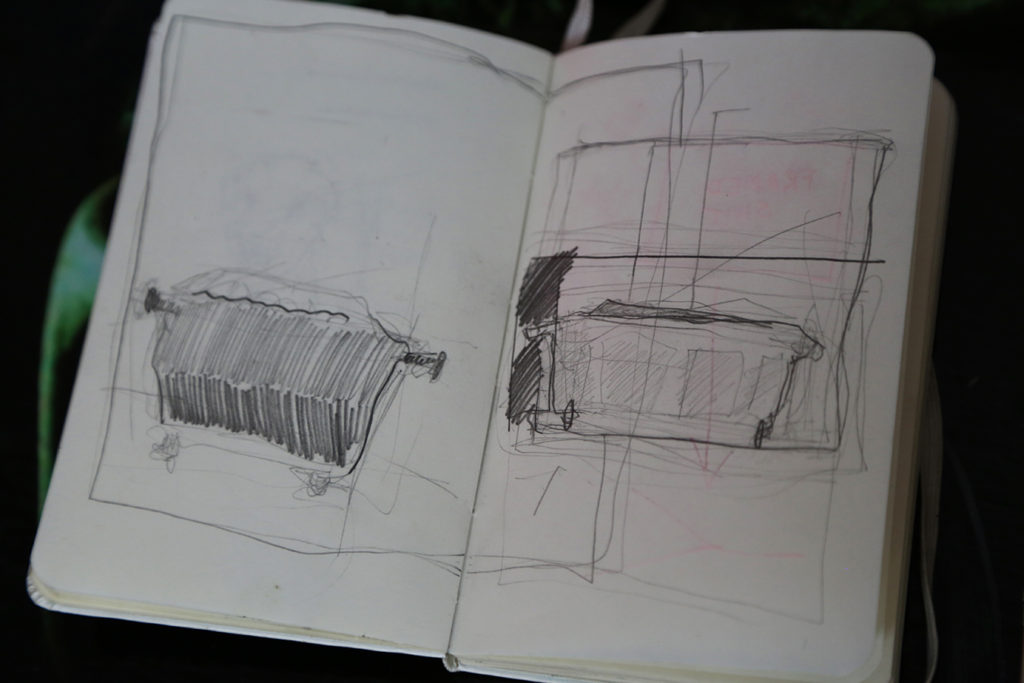

ER: The paintings themselves work as sketches for each other. So, if a shape shows up in one painting that I like, but it’s too early in the process, then perhaps it will travel to a field that is more developed. So, I start five at a time, sometimes more, so that I can use the paintings as sketches for each other.

Some of the gestures are really choreographed and some of them are messing around. Most of the layers happen in one go, especially under layers, because they are acrylic and dry quickly. So you only really have one shot to make it work. And then you have to wait for it to dry.

People ask, “How do you know when paintings are done?” I always say that you don’t know when they are done, but you know when you have gone too far—immediately! And then you have to fight it back to the place you had it before you killed it.

ER: It is an interesting transitional point that you’ve come into now. The show is up, and I’m thinking about where we are going forward. I’m mostly excited about these strange, fluorescent paintings.

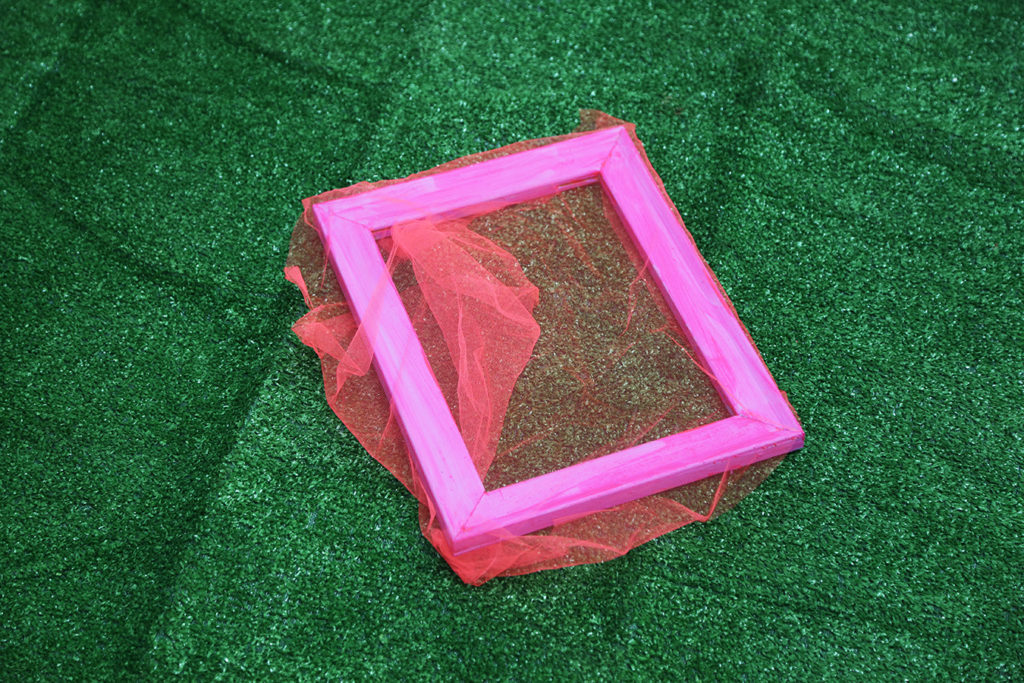

I’m thinking about screens and color theory that is more aggressive. I think I am sneaking up on sculpture and thinking about moving into a more three dimensional way of thinking. There is a piece in the [707 Penn Gallery] show that has a tiny bit of green fruit netting on it. That was like first blood. So, this is second. [Fiddles with pink netting and a frame on green grass carpet]. Most of my studio practice is throwing things on top of each other, whether it be throwing a layer of paint on something or moving things around spatially. Rectangles on rectangles. [Looks at new configuration]. I like that. That’s doing something.

ER: This is called plastic canvas, and I didn’t know that, because I found it in a dumpster somewhere.

DB: Where was it?

ER: It was outside of Artist & Craftsman. It wasn’t exactly a dumpster. I don’t want to sound more punk rock than I am. It was on top of a pile of things that were going to be thrown away. People use it to build wax and cardboard structures. But it has a weird op-art thing going on.

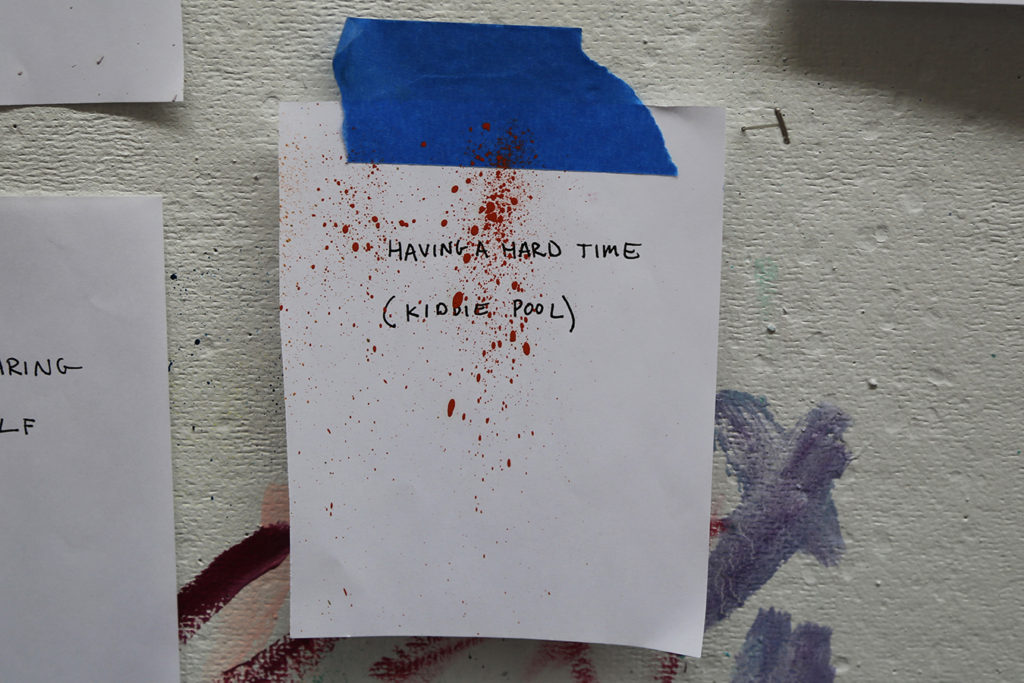

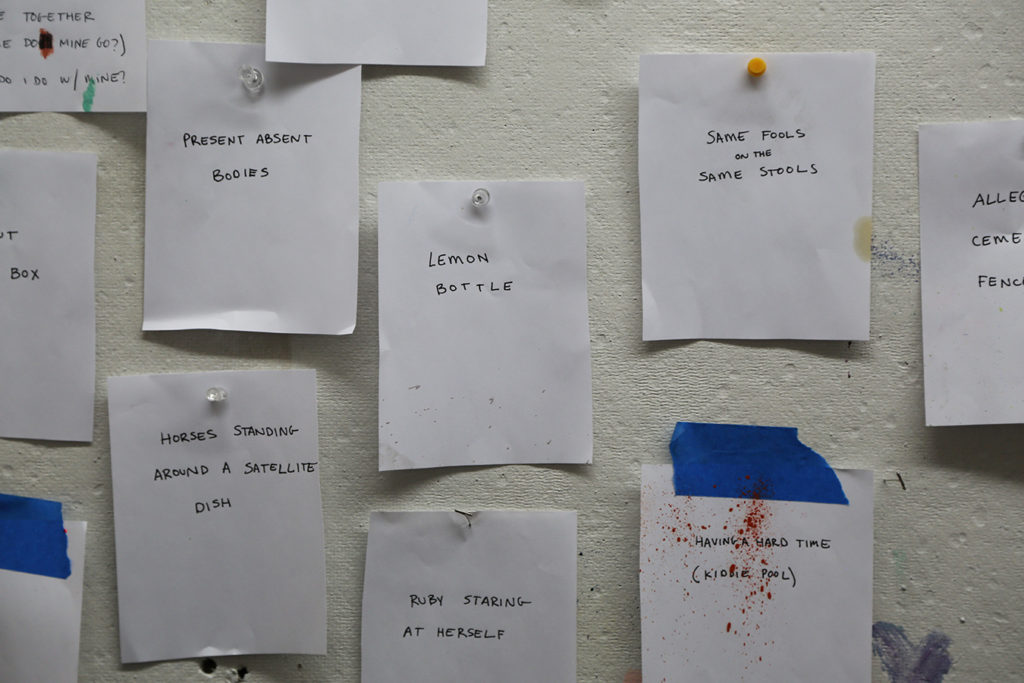

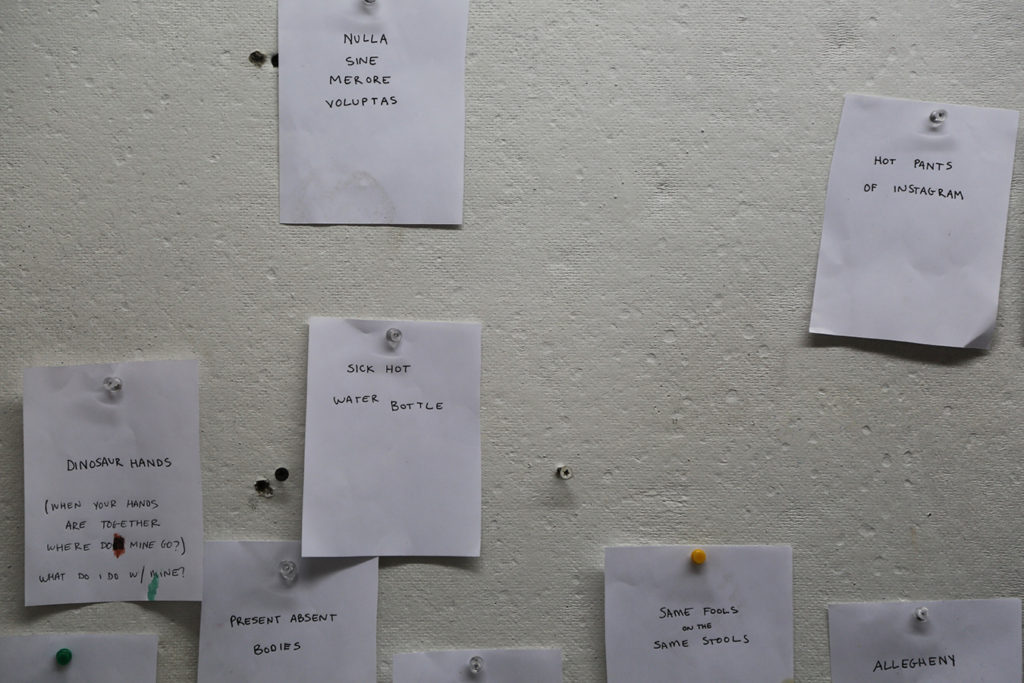

ER: I come up with titles much faster than work so I have all of these little thoughts that hang out with me: “Deflatable floral print.” “Ruby staring at herself.” “Iceberg lettuce.” “The angle of repose.” “Same fools on the same stools.”

ER: The second body of work that is going on now—I started taking photographs of the inside of my mouth with my cell phone camera, and I’ve been printing them on different papers with aluminum leaf overtop. This one here is printed on Yupo, which is cool because it is a plastic coated paper that dries slowly. It runs through the printer cleanly, but you can push the ink around while it is drying for 24 hours. I don’t think it is necessarily important to have that original story present in the structure. I’ve obscured it pretty completely, but I still appreciate images that relate to real life even if they’re completely abstracted.

ER: The two women with the flowers are actually my mother’s bridesmaids. I digitized their wedding video. That particular side-eye is because my father is sobbing. I don’t know what to do with it yet. But the color was so great, the turquoise in their gowns, the perms. They’re my patron saints right now.

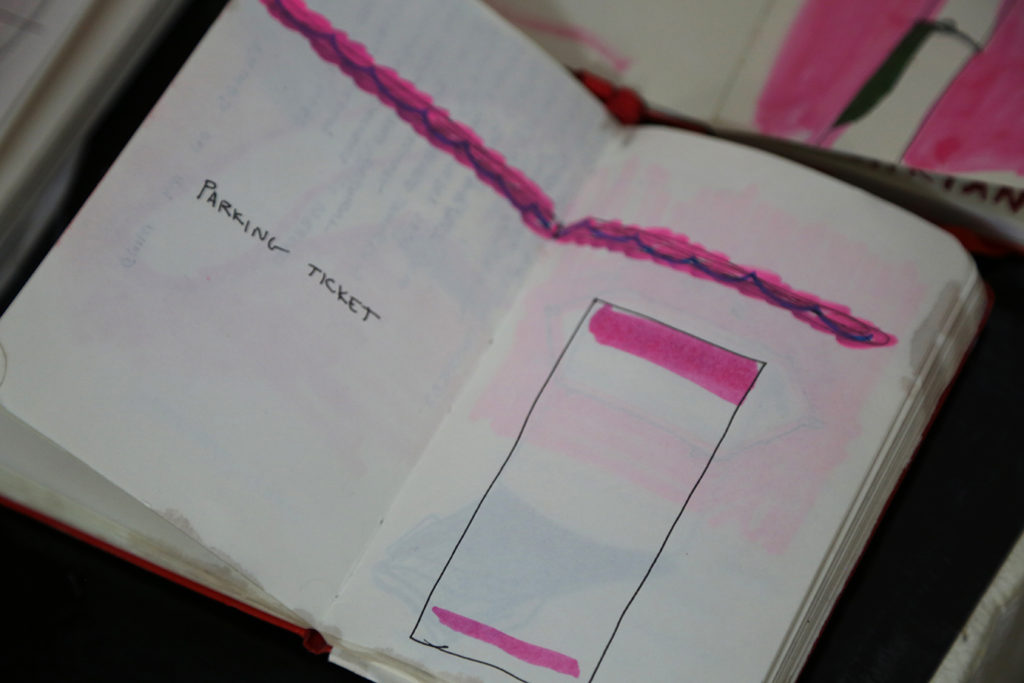

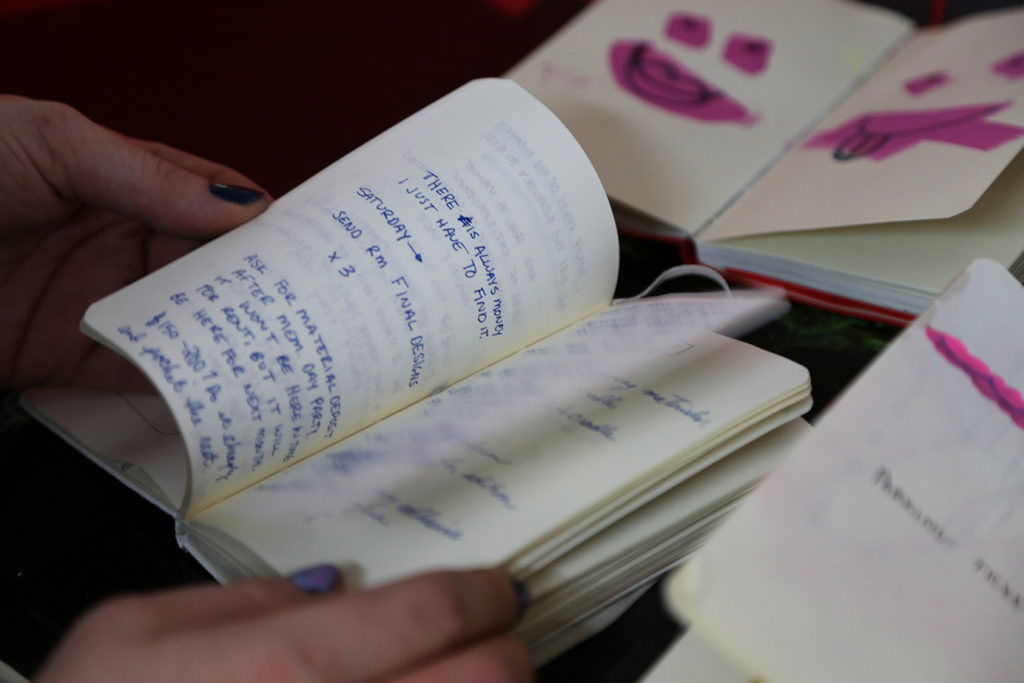

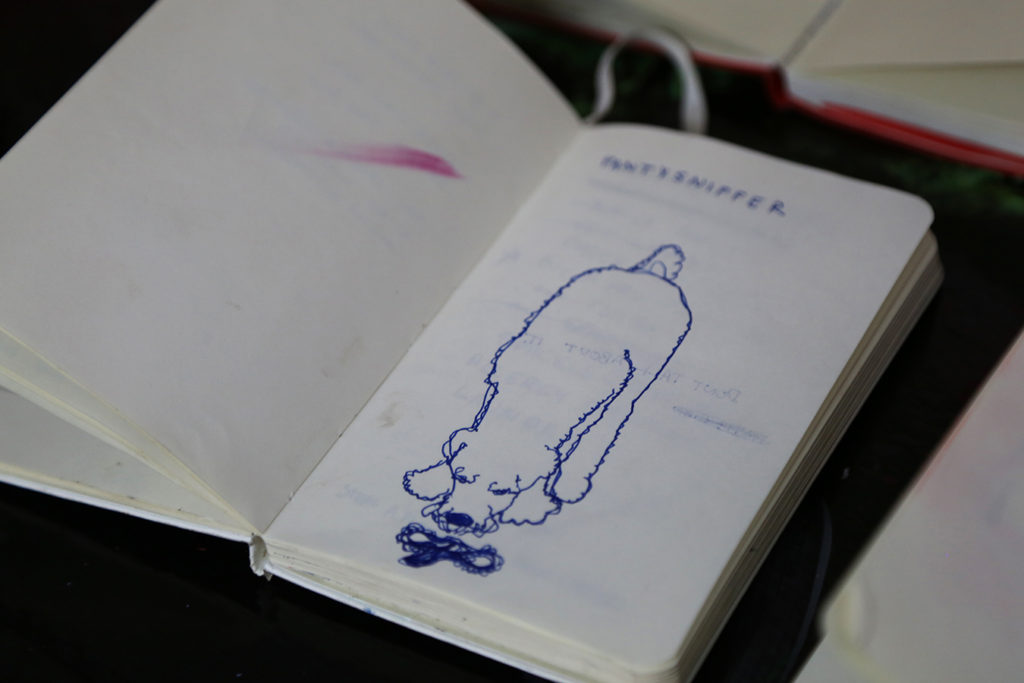

ER: Most of the ideas happen in sketchbooks first. Well, they show up and I forget about them for two years, and then they come back. Parking tickets: a reoccurring theme.

ER: I get to the paintings through writing, but the writing ends up being a sketch that doesn’t get shown to anyone.

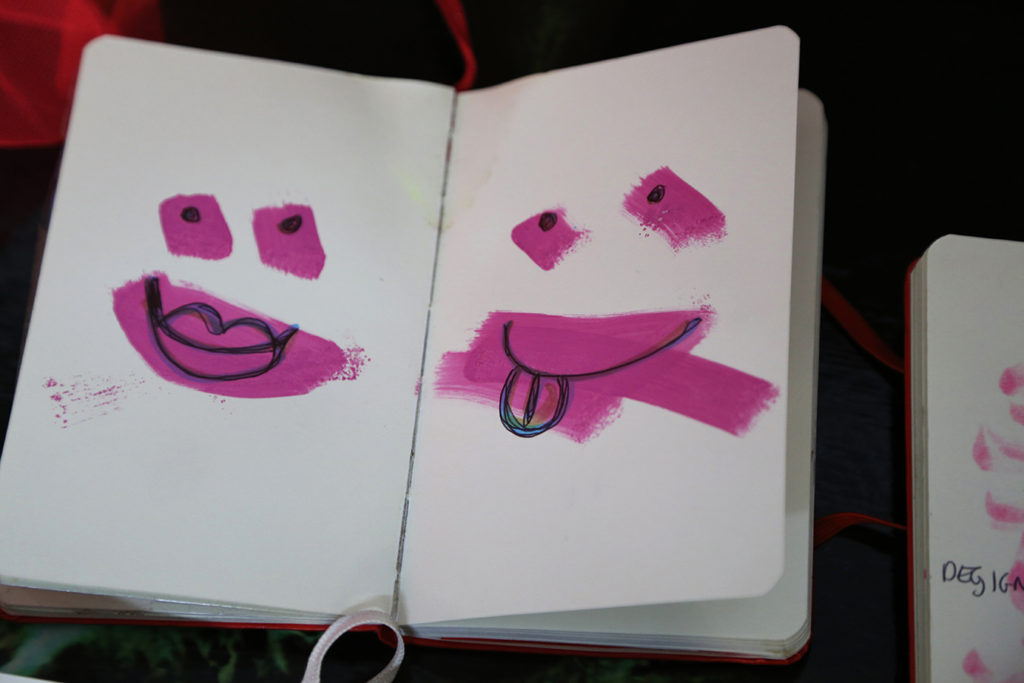

ER: These were the bar entry stamps that were drawn on a friend of mine and my hand the first time we ever made out.

DB: Which bar was it?

ER: It was Howler’s. They weren’t stamps; they got creative. It was a sharpie. He got the lips. I got the tongue.

ER: I had a sketchbook that I cared about a lot that had soup spilled on it. It was fish soup. For a long time, cats were my best friends.

ER: Ghost Guts is the name of a friend’s band. This was a sketch—perhaps it will become a t-shirt at some point. I was trying to figure out how to capture entrails and ambivalence in the same drawing.

[Like many in Pittsburgh, our conversation turned to the topic of Pittsburgh].

ER: I’ve been in Pittsburgh for eight years. I was at Carnegie Mellon for the first four doing painting. After I graduated, I was at Radiant Hall for a little while. Then I consolidated my art practice with my living practice, which had benefits and aggravating factors. I was in Highland Park. I had an attic space that was $500 a month for a bedroom and a studio space, but I missed working with other artists and missed being able to tap people on the shoulder who weren’t my roommates to ask them to stare at things, because your roommates get sick of that after a while, especially if they are in grad school.

So, I came back here [to Radiant Hall]. It’s kind of a special network. You not only have access to other people making cool stuff, but you access to the connections that they are making, to people inside and outside of the city. If you happen to be around while someone is having an important studio visit, then you get the benefit of that relationship. It’s been really fruitful and helpful.

[We spoke about the recent acclaim for work by Terry Boyd, Gavin Benjamin, Seth Clark, and other Radiant Hall artists].

ER: That’s another benefit. You see what a career five years ahead of your own looks like, the benchmarks that have been hit. You have access to those conversations: “What happens when I sign a contract with a gallery? What should I watch out for? How do I know when I’m being aggressive enough?”

ER: It’s like gambling. Now I’m lucky enough to say, “What did I sell a painting of this size for before?” Then I can slowly work my way up from there. But the large paintings, like this painting, “Two Rabbits,” which is in its fetal stages, would go for $2,400. Those are the types of rabbits that live around my parents’ house in New Jersey. It comes from a fortune cookie that I once received that said, “The man who chases two rabbits catches none.” For a while, I thought it described my painting practice, because I couldn’t decide between figuration and abstraction and I was trying to do them both at the same time. Which I still am, but I’m focusing on one at a time now.

But pricing is tough because the market in Pittsburgh is tough. Being an emerging and younger artist, you want to price work that is accessible without cutting yourself short. But there is very much a threshold for what you can sell paintings for in Pittsburgh despite your clout. I haven’t reached it yet, which is good. [Laughs]. I think it is around ten grand.

DB: Do you have ideas on how to fix the market issue in town?

ER: There are people in this city who get excited about artwork and buying artwork. I don’t think that the market doesn’t exist, but there aren’t mechanisms in place for bringing people into the scene. That’s a problem that no one is particularly at fault for. It’s partially getting to hear about things in a timely manner.

Facebook has become the one of the only ways to reach people, but those people aren’t always the people with financial stability to buy your paintings. So, how do you get people comfortable with buying art when they could be buying things that seem more tangible or more immediately utilitarian?

Using spaces in original ways is one solution. I was talking with David Oresick [Executive director of the Silver Eye Center of Photography] about his pop-up gallery, The Goldmine, which is essentially his upper living room. He has shows every couple of months. He said that happens all the time in Chicago. In Pittsburgh, there are a lot of spaces that could be utilized in that way. You surprise people and bring them in instead of hunting them down and dragging them in. I don’t think there is a single solution, but having more writing, having more people talking about art, having a clear calendar of events somewhere in the ether that isn’t Facebook. Talking is the first step, like what we’re doing right now.

ER: When you live in a small city which is simultaneously insulating and insular, you don’t want to alienate anyone. So, for lack of a better term, you get caught into a circle jerk, and quality reaches a ceiling when you can only say good things about shows. And that’s a larger market problem. By the time the critics get there, everything has been done. Collectors have found the people. Curators have made the decisions. Then criticism becomes a mode of advertising instead of a mode of critique. I don’t think that is just a Pittsburgh problem. When you have an art scene that is trying to make a name for itself, it’s necessary to get good press, but you are shooting yourself in the foot if there isn’t lively critique.

You know, I came out of art school, so I’m used to tearing something apart in an emotionally-neutral way. But the public at large has a much harder time doing that, and things can come across as being malicious when being critical is necessary and helpful.

![]()

Elizabeth Rudnick was born in Herlev, Denmark and received her BFA from Carnegie Mellon in 2012. See some of her work documented on her website here.