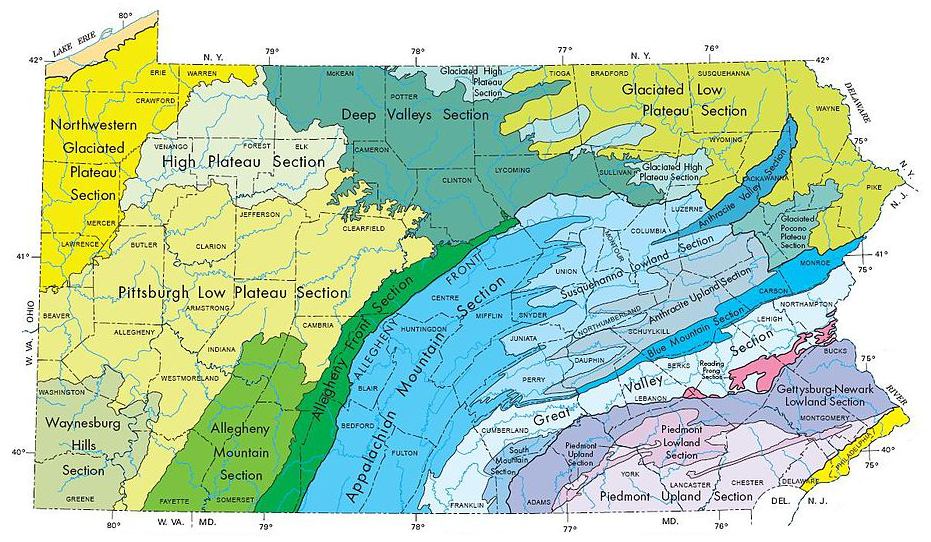

Most are plain and dull, without any notable texture or shine. These are sedimentary rocks, like the kind visible in the eskers that leer over Western Pennsylvania’s highway system. When I walk in Frick or Schenley Parks, Pittsburgh’s wilder areas, I always dig into the moist earth, and there, too, I find sedimentary rock. To say that Pittsburgh is a sedimentary city would be accurate on many levels: It’s gritty and dark and sits on a plateau that extends three miles into the earth.

Sedimentary rock breaks into well-drained, rocky soil, a fact discovered by the Monongahela people who once lived in the region. Contrary to their hunter-gatherer ancestors, the Monongahela planted the land, moving only when the soil became depleted. When European settlers arrived several hundred years later, they followed suit, using many crops that they brought from the Old Country: potatoes, squash, wheat. They also brought distilling techniques, laying the groundwork for what is today one of Pennsylvania’s favorite pastimes.

The incident known today as the Whiskey Rebellion stands testament to both the efficacy of Washington’s new national government and to the fierce protectiveness with which Western Pennsylvanians guarded their land—and their alcohol.

Pennsylvania is a state with a historic love of alcohol, and as a Pennsylvanian writer who specializes in beer and spirits, it was natural that I should know all about the Whiskey Rebellion, and many other facts besides: For example, I know that for a time in the late 1800s Pennsylvania and New York together represented one of the premier regions in the world growing hops, an herbaceous vine-like plant in the Cannabaceae family that’s one of the four main ingredients in modern ales. I know that Latrobe Brewing Company, founded in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, was at one time one of the largest breweries in the country, and Yuengling, headquartered in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, is still among the top. And, in what’s one of my favorite pieces of Pennsylvania beer trivia, I know that the Pittsburgh Brewing Company, which began operations as the Iron City Brewery, weathered Prohibition by selling ice cream and soda; they came back after the repeal of the 18th Amendment to produce IC Light, my father’s favorite beer. (Later, after moving to Charlotte, North Carolina, my father would look at draft lists at restaurants and express wistful regret that they didn’t carry IC Light. With a sigh he would resign himself to a Heineken.)

![Hops. [Kate Ter Haar/CC BY 2.0]](http://theglassblock.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/6141709859_b013779db2_b-1024x683.jpg)

If Pennsylvania brewers today want large quantities of conventional hops, they typically need to source them from the other side of the country. If they prefer organic hops, they must turn to Australia or New Zealand, 11,000 miles away. Grain also needs to be imported. In 2012, Pennsylvania grew 53,000 acres of barley for feed, and only five for use as malting barley, which goes into whiskey and beer. Five. Only five acres in the entire state. And only one Pennsylvania-based commercial facility is even capable of malting the barley, a necessary step before it can be used in drinks.

There are exceptions to the rules, of course. Wigle Whiskey is famous for making many of its products with Pennsylvania ingredients. Braddock’s Brew Gentlemen produces its Homegrown Saison, which uses 100 percent Pennsylvania malt. Arsenal Cider in Lawrenceville uses apples from orchards located a few miles away. But these are exceptions, not rules, and that worries me.

![]()

I love this place—its rivers and hills, the smell of the air in fall, the distinct dendrite branches of a red maple against a brilliant blue winter sky.

I’ve driven in Manhattan and England, and in Berkeley, where houses cling to the hills like kittens on curtains, and in Laos, where only thirteen percent of the country’s roads are paved and trucks scream past on blind turns, passing so close you could reach out and touch them. But Pittsburgh, with its labyrinthine, pockmarked roads, mysterious one-ways and right-turn-onlys, beats them all for difficulty. At night, I dream of getting lost in Pittsburgh and finding my way via geology: a left at the shockingly yellow ginkgo, a right when you hit that rolling green lawn in Schenley Park. This land created me. Without it, I wouldn’t be who I am.

Similarly, the land gives identity to its more literal fruits. Every layer of sedimentary rock, every breeze that blows through the sugar maples, and every drop of hydraulic fracturing flowback that reaches the water table shape these fruits in some way. Alcohol, a product of these fruits, is the land distilled, and it takes on characteristics of its place—of wine, we say terroir, from the French for “land”—in a way that makes it incapable of being reproduced anywhere else in the world. To taste a product made from Pennsylvania ingredients is to taste Pennsylvania—its light, its water, its land.

When we lose our connection with the land, we begin to lose our identity. I look at the rocks on my kitchen table and realize that I am who I am because of Pittsburgh’s sedimentary composition, just as I am a product of a swirl of German, Polish, and Italian cultures, of gray days and steel mills words like “slippy,” “chip-chopped.” Consuming local connects us with our land, in turn connecting us with ourselves.

Once, not so long ago, Pennsylvania supported a thriving community of brewers and distillers that used local ingredients in their products. Today, despite a lack of infrastructure and recent precedent, a few beverage makers have been brave enough to continue that tradition. But I wonder: Who will follow their lead?