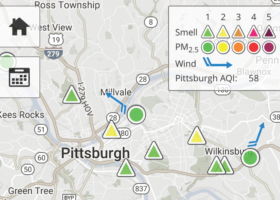

In November and December of 2015, representatives from nearly every nation met in Paris for the COP21 UN Climate summit, where they agreed to cut or curb their carbon emissions to stay the increase in global average temperature to “well below 2°C.”

The Paris Agreement was celebrated as a landmark, a “Kyoto 2.0” that would—fingers crossed—mitigate the worst effects of global warming. The planet has already moved 1°C beyond pre-industrial levels; anything above 2°C is considered the threshold at which catastrophic weather events become the norm and a sixth mass extinction event kicks off in earnest.

Even before Donald Trump was elected President (he has vowed to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement) critics had called the agreement inadequate: It lacks a binding enforcement mechanism to cut emissions, and some studies predict temperatures will rise 2.7-3°C even if every nation meets their pledge to cut or curb emissions.

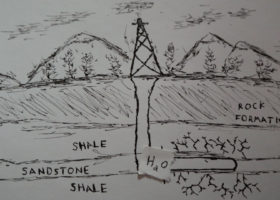

“There is no action, just promises,” said former NASA scientist and climate expert James Hansen. “As long as fossil fuels appear to be the cheapest fuels out there, they will be continued to be burned.”

Fed up with a tepid response to a pending calamity, a grassroots movement has emerged wielding a tactic that helped bring down apartheid in South Africa: divestment.

New movement, old tactic

The thinking goes like this: If enough institutions sell off their fossil fuel holdings, it will reduce the industry’s share prices and profitability, hastening a switch to renewable energy and leaving oil and coal in the ground rather than the atmosphere.

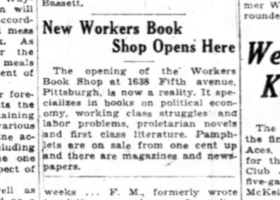

The movement began in 2011 when a handful of students at Swarthmore College petitioned their school to divest their fossil fuel holdings. As of September of this year, 600 institutions worldwide have divested, mostly philanthropic trusts (Rockefeller Brothers Fund), university endowments (Yale and Stanford), religious groups, and even a small number of city pension funds.

For a short time this year it seemed imminent that Pittsburgh would join those ranks by divesting their Comprehensive Municipal Pension Trust Fund from its carbon holdings.

Local advocates, Local action

Divest Pittsburgh formed in late 2013 after a speech at the Thomas Merton Center by writer and climate activist Bill McKibben, who popularized the push for divestment in 2012 when his 350.org environmental organization launched its Go Fossil Free: Divest from Fossil Fuels movement. [Read The Glassblock’s May 2016 interview with members of Divest Pittsburgh.]

Divest Pittsburgh petitioned city officials, and in January 2016 City Council President Bruce Kraus spoke out in support of fossil fuel divestment.

Emails obtained by Right to Know request dated January 26, 2016 show city Finance Director Paul Leger circulating a draft resolution with Kraus that called for the city pension fund to divest its holdings from the top 100 public coal companies and the top 100 public oil and gas companies globally within five years.

Kraus had a natural ally in Mayor Bill Peduto, who attended COP21 as a member of the Compact of Mayors, an international coalition of 550 city leaders committed to taking action against global warming. He used the occasion to announce a series of environmental goals for the city to reach by 2030, including the creation of a fossil fuel divestment strategy for City of Pittsburgh funds.

“Pittsburgh and other cities are on the front lines of the climate change crisis,” Mayor Peduto said at the time, “and it is our responsibility to address the deep challenges it is creating for us, our children, and our grandchildren”

But any post-COP21 momentum was lost when it was determined that the issue is a matter for the Pension Board to consider, not City Council. Kraus’s bill was never introduced, and the issue was jettisoned, delegated to the seven-member Board, which includes Peduto, Kraus, Controller Michael Lamb, three union representatives, and a mayoral appointee.

The “Moderately Distressed” Pension Fund

A total of 3,161 firefighters, police officers, and other municipal employees pay into the city pension fund from which 4,209 retired and inactive members collect.

As of June, the comprehensive pension fund had an unfunded obligation of about $550 million, meaning that 45% of its $1.2 billion is not budgeted for. That puts the fund in “moderate distress”—and a 2015 Compliance Audit stated “it is clear that the City of Pittsburgh’s Comprehensive Municipal Pension Trust Fund continues to face serious financial difficulties that city officials must address.”

Sixty percent of the $655 million fund (about $400 million) is invested in mutual funds or an equivalent. Marquette estimates that 5% (or $20 million) of that is invested in the energy sector, but they cannot say how much exactly.

“To tell what is actually in the mutual funds is nearly impossible because it changes nearly every day,” says Leger, who also serves as the Fund’s Executive Director.

Those who favor divestment say that it makes financial sense to divest now in order to avoid falling victim to a collapse in oil like the one endured by coal. Pittsburgh’s pension fund lost $16 million in 2015, in part due to a 30% decline in oil values.

“A lot of public pension funds lost a lot of money to coal,” says Jamie Irwin, associate director of the Mayors Innovation Project.

Irwin, who has spoken with members of the Peduto administration regarding divestment, warns that “we have indications that something similar is likely to happen to oil, and at some point the carbon bubble really is going to burst.” (Irwin shared this before the recent presidential election; fossil fuel stocks have since risen given Trump’s campaign pledge to reinvigorate the domestic coal and oil industries.)

“Peduto’s email read four words: ‘We need a policy.'”

If the bubble is not set to burst in the immediate future, oil may look like a shrewd investment. Crude oil fell to a ten-year low, $27 a barrel, in January. It may seem like a textbook case of “buy low, sell high”—and the Pension Board has a legal obligation to maximize investment returns for members.

A parallel can be found in tobacco. After enduring a lengthy divestment campaign of its own, the tobacco industry has become an alluring investment option for cash-strapped funds. For example, a study commissioned by the nation’s largest pension fund by assets, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, shows that they missed out on almost $3 billion in profit since divesting from tobacco in 2000.

What comes next?

Since the issue became a matter for the Pension Board, the issue has languished. Neither Kraus or Peduto have called for a vote on divestment or a vote to commission a study of the financial implications of divestment at any of the three Board meetings this year. Mayor Peduto has not appeared at any of the three pension board meetings this year, in person or by phone, so any introduction of a measure would have fallen to Kraus.

This inaction stands in contrast to the content of emails sent by Mayor Peduto to his staff, obtained by Right to Know request.

On November 24, 2015, the Mayor forwarded a “Municipal Primer for Climate Investing” from the American Sustainable Business Council to Leger, Acklin, and policy advisor Alex Pazuchanics. Peduto’s email read four words: “We need a policy.”

On May 5, 2016, in response to an email from Divest Pittsburgh advocating for divestment, Mayor Peduto wrote to his chief of staff, Kevin Acklin, and Comprehensive Municipal Pension Trust Fund executive director Paul Leger, saying “I want to find a way to divest by end of year.”

Despite these statements, Acklin says that present conversations regarding divestment in the city take a long-term view of the process—in the neighborhood of 10-15 years. He says that the current pension crisis in Pennsylvania precludes more immediate action and that Peduto and Kraus don’t have the votes on the Board to pursue it further.

“To [divest] immediately would be irresponsible,” says Acklin, “but to do so over time is not only good for the planet and environmental sustainability, it’s probably a good investment decision … as the world moves away from fossil fuels and invests more in renewable resources.”

Will it work?

Divestment’s greatest power is its ability to shape perception. Experts still debate how much of a financial impact the movement had in bringing down South African apartheid, but undeniably the divestment campaign helped shape its perception as an abhorrent practice and spurred the moral imperative that precipitated its demise. Today’s generation of divestment crusaders hope to cast their campaign in much the same light.

“The cost of prevention pales in comparison to the cost of inaction…”

One of the few American city pension funds to divest from fossil fuels is Providence, Rhode Island. In July 2015 the city divested from 15 large coal companies, known informally as the “Filthy 15,” a list that includes companies with strong Western Pennsylvania ties, including Consol Energy. Four of the 15 have filed for bankruptcy, including Peabody Energy, the largest private-sector coal company in the world.

The total amount Providence divested was less than $2 million—barely a rounding error for the $5 trillion fossil fuel industry—but the city’s mayor Jorge O. Elorza said his administration had made sustainability a priority and that it was important that they lead by example. Rhode Island, “the Ocean State,” is directly threatened by rising sea levels and a U.S. Senate report shows swaths of Providence underwater with a three-foot increase of the Atlantic Ocean.

The day before Thanksgiving 2016, Mayor Peduto joined 41 other mayors of small and large American cities in signing an open letter to President-elect Trump asking him to take action on climate change.

“The cost of prevention pales in comparison to the cost of inaction, in terms of dollars, property and human life,” the letter reads. “As our incoming President, as a businessman, and as a parent, we believe we can find common ground when it comes to addressing an issue not rooted in politics or philosophy, but in science and hard economic data.”

Donald Trump’s election has given the fossil fuel industry a reprieve, at least in this country. Whether it makes long-term economic sense for Pittsburgh’s distressed pension fund to divest from fossil fuels can largely be determined by a study. But whether or not city leaders have the conviction, or mandate to pursue it, will be learned in time.