As part of The Glassblock’s sponsored partnership with the New Hazlett Theater, we will be presenting a series of editorially-independent previews and reviews of the 2016-2017 Community Supported Art (CSA) Performance Series. Follow along here, and learn more about how you can experience this season’s CSA here.

![]()

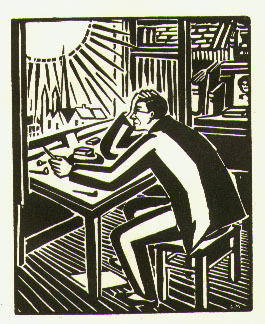

Though he was born in Chicago and raised in Englewood, New Jersey, artist Lynd Ward’s year in Leipzig, Germany, from 1926 to 1927, was to have a profound influence on his work. It was there that he honed his skill in etching, engraving, and lithography, much of it in the German Expressionist style dominant during those interwar years. Like the uncanny set design of the 1920 silent film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the woodcut storytelling craft that grew in Weimar Germany utilized fields of black and white, shadow and light, to create stark, sometimes jarring, visual contrast to achieve moody, melodramatic, or downright sinister tones. Typically wordless, these early graphic novels relied solely on painstaking imagery to tackle topics like political and economic injustice, oppression, and other socially-minded, earnest subjects. “To make a wood engraving is to insist on the gravitas of an image,” famed American cartoonist Art Spiegelman wrote in 2010. “Every line is fought for, patiently, sometimes bloodily. It slows the viewer down. Knowing that the work is deeply inscribed gives an image weight and depth.”

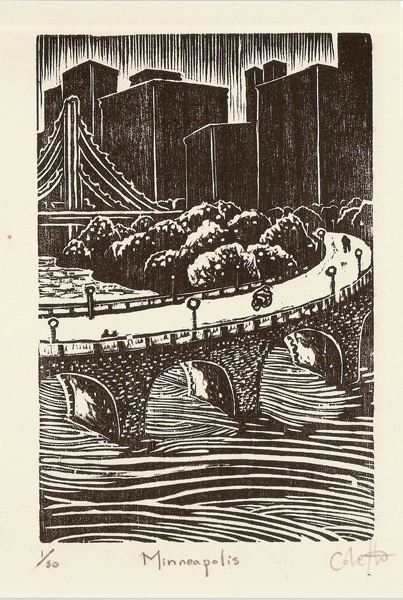

For Pittsburgh artist and storyteller Cole Hoyer-Winfield, Lynd Ward’s legacy is that of “the American noir visual style,” with “an invisible influence on American imagery,” he said one recent afternoon as we visited him in his Lawrenceville home. Inspired by the creative work of Ward and others, Hoyer-Winfield studied printmaking at the University of Minnesota, graduating in 2009 and soon after exhibiting his work in shows like the Minnesota Center for Book Arts, the Biennial International Miniature Print Exhibition in Vancouver, Canada, and the Universos Paralelos Print Exchange in Curitiba, Brazil.

But while this foundation in printmaking has had an influence on a personal visual language, “My stories were being trapped [by a] laborious woodcut printmaking process,” he said. And, at the end of the process, the work remains in a book, or perhaps in a gallery, but ultimately static, a frustrating conclusion for a storyteller like Hoyer-Winfield. Then he discovered the crankie.

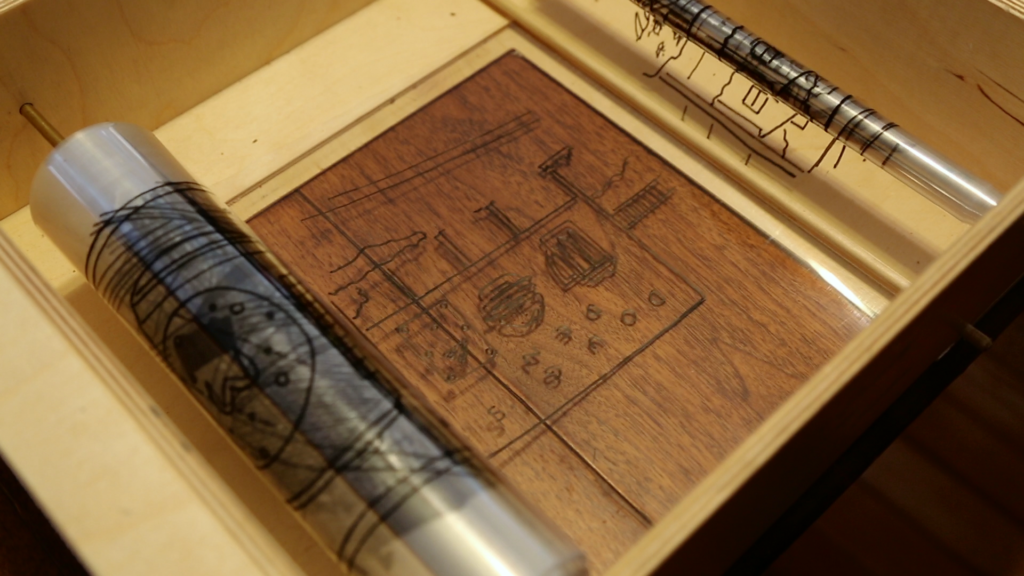

Slowly, with a mechanical pacing, Hoyer-Winfield turned a small black hand crank attached to a rectangular, wood-framed box, one of two identical crankies atop his kitchen table. “My dad, who’s a woodworker, helped me build these,” he told me as I peered into the curious contraption. “He put a little engraving on the side.” A thick roll of translucent plastic unwound, passing inked trees, buildings, and line drawings of urban landscapes through the frame. The visual effect of the crankie—or “moving panorama,” its more mannerly moniker—is not animation, which requires a rapid succession of frames, but, together with a source of illumination (in this case, an overhead projector), it instead produces a scrolling imagery that’s whimsical, charmingly primitive, and full of personality.

This approach also allows a more personalized, even improvisational, storytelling style. “I can just rattle it,” Hoyer-Winfield explained, “and the whole wall will look like it’s shaking. Or I can mess with the focus, block the light, or add other hand elements.”

Monthly puppet shows put on by college friends attracted his attention, and it was through these performances (which took place in conjunction with full moons for extra ambiance) that he first became familiar with the crankie. “I thought it would work really well with my [printmaking] style, and, using a projector, I could draw as many images as I wanted, as large as I wanted, instead of being limited to a certain size of paper.”

Marrying his printmaking background with this newer, sequential art direction, Hoyer-Winfield created Midnight in Molina, a crankie performance that plucks themes, characters, and ideas from past stories he has written. The fictional town of Molina is “a jungle town that was founded as a crystal mine, with a post-industrial backdrop,” Hoyer-Winfield told us, an amalgam of different places he’s spent time in (Hoyer-Winfield, who also studied Portuguese at the University of Minnesota, spent a semester in Brazil, which explains the tropical influences, and his time in the Midwest and in Pittsburgh surely point to the post-industrial). Midnight in Molina dips into the magical and mysterious—he cites Twin Peaks as a stylistic influence—and its characters reflect ideas of optimism and skepticism, with echoes of Candide, and the way that different people deal with the frighteningly consequential impacts of chance.

“The way I ended up in Pittsburgh, the way I’ve ended up in a lot of different places, supplied with different opportunities or met important people or had great ideas—have totally been based on chance,” Hoyer-Winfield shared. “The thinnest threads of events have created these massive, transformative experiences in my life.”

![]()

On Thursday, October 20, with an overhead projector—and musical accompaniment by Minneapolis-based Orchard Thief and Pittsburgh-based Swampwalk, Matt Breslov, and Jeff Ryan—Hoyer-Winfield will perform Midnight in Molina, kicking off the 2016-2017 New Hazlett Theater’s CSA Performance Series. Buy your share of the CSA here and get admission to the entire season of performances. The Glassblock will be there—check back afterwards for our review of Midnight in Molina, and again throughout the rest of the CSA series.