Artists dedicate significant time to each creation, and, often, reviews of artists’ exhibitions strive for a summation that can leave specifics unexplored. Our series The Object is a an attempt at a small-scale course-correction, focusing conversation on one single work of art in order to investigate its concepts, materials, and execution in great detail.

![]()

It’s suitable that the first iteration of our series The Object features Pittsburgh Center for the Arts’ Artist of the Year Richard Pell. His current exhibition The Myth of the Great Outright Extraordinary! is a collection of objects, small and large, old and new, containing some element of known or little-known history, presented alongside a collection of stories. In one room lurks a large multi-sided structure titled Pell’s Cabinet of Ambiguities. Like the show, it is literally filled with objects—a postcard, a record, an E-meter, a puppet. Though there are other rooms with other objects, the cabinet struck a few notes both personal and intellectual. For the first in this series, installation artist Natalia Gomez joins The Glassblock’s David Bernabo for a discussion of The Object.

David Bernabo: First of all, we should talk about how we just spent five minutes looking at the flies in the gallery, trying to decide if Rich Pell genetically engineered them and stuck them on the walls.

Natalia Gomez: Well, they were so perfectly placed. There was a fly on a screen projection and it seemed so intriguing. Then a second fly was perfectly perched on a piece of paper, partially blocking a light from throwing too much glare on a piece. It was like an Easter egg in a video game.

DB: And then they flew away. Because they were real flies. So, anyway, we are looking at a multi-sided structure, filled with curiosities.

NG: Searched, found, preserved objects. And all of the sides of the structure have windows that allow the viewer to see the objects. There are old-school telephone booth phones under each window.

DB: If you pick up the telephone, you hear a short story… or a description of the object.

NG: Well, I would say a short story is a really good way to put it. Though the narrator does start to describe the objects, the narrative is larger—there’s a personal feel to the stories.

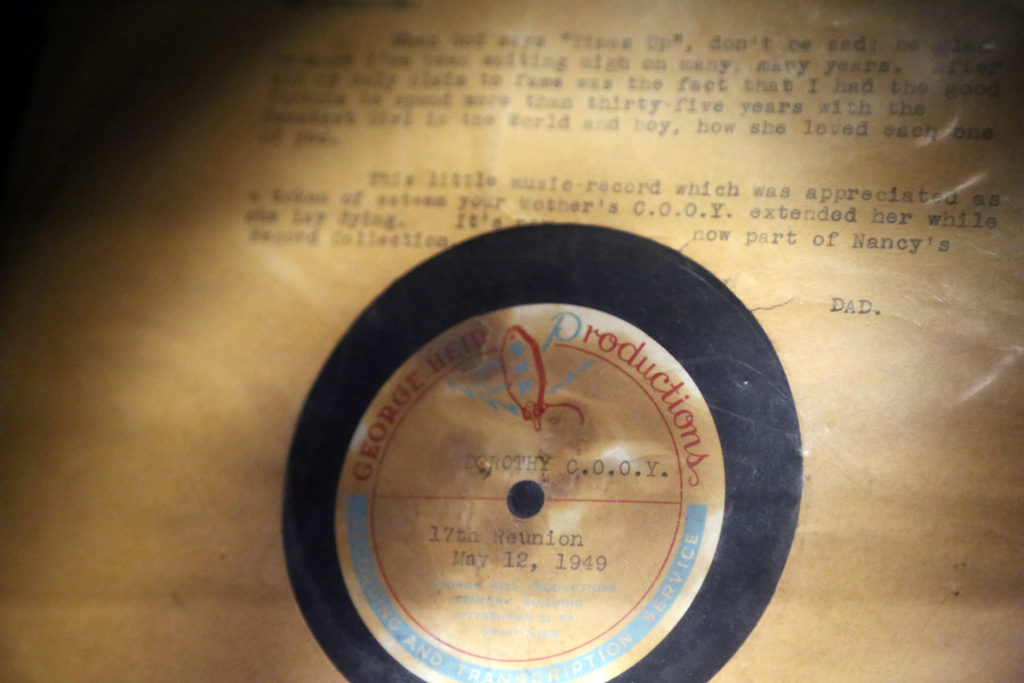

DB: This record of Dorothy’s friends singing to her on her deathbed was really emotional and sad. I was surprised how a record, heard through a phone, could have such an impact.

NG: What’s interesting, thinking about the intimacy of the experience, is that you are picking up a phone and you hear another person on the line. There’s an ambiguity within this action, but also the intimacy of hearing the voice on the other end—hearing how her friends are parting ways with her, and how that record continued to exist.

DB: This one speaks to me a bit, because my grandfather recorded a solo accordion piece on one of those instant recording booths, like the Voice-O-Graph. I have a few of those one-off recordings. So, this object and this story relate to my personal narrative. Alternately, the UFO themes in a different window don’t speak to me personally—it’s just an interest of mine, but all of these windows work on different levels of nostalgia and will affect people differently.

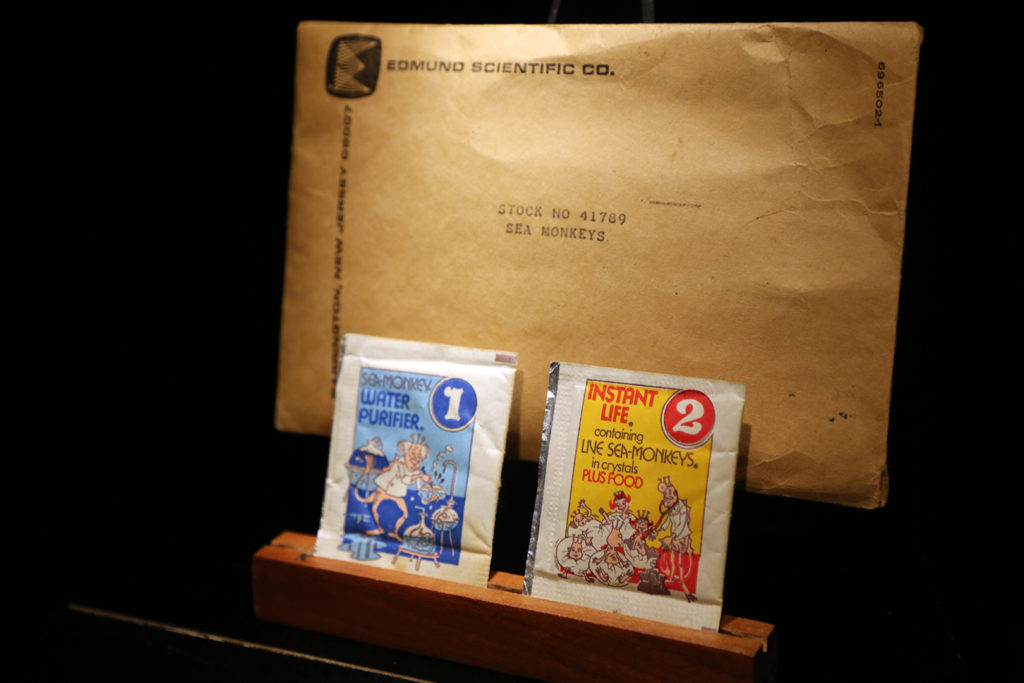

NG: I think that is one of the really powerful things about this piece as a whole. Each object and each narrative are so different and will harp on different interests, playing on your own history and personal connections. For instance, looking at the Sea-Monkey packets. Not only is there humor in that story, but I grew up with a mom who—throwing things away can be difficult sometimes and, as artists, we like to keep all kinds of random stuff. So, in Pell’s piece, opening a drawer, the narrator finds old Sea-Monkeys and asks, How did this come into my house? And I remember opening a drawer and finding this beautiful little still life of an empty pencil case, a corner of coupon, and a button to a shirt that no longer exists. I thought that this is a really great moment of discovery. And that sense of discovery runs through all of these windows.

DB: This kind of setup for an artwork can be cumbersome and I often don’t make it all the way through.

NG: And also daunting, because if you know there are ten experiences within the piece and you know you need to pay attention to each experience, I never make it too far. I generally listen to a bit and move on to the next room. But in Pell’s piece, we both made it through all the objects!

DB: One thing that helped our attention spans was that the narrative literally sped up about 20 seconds into each story. The pitch and the speed of the narrator increase. That’s a great detail, because the listener can grasp the story and, once they’re hooked, the narrative moves quicker and propels you to the conclusion of the story.

NG: That’s a really great point. Going through the motions of interacting with the piece—you approach the dim panel, you know there is an object and you want to approach it. You pick up the phone, which is a wonderful act of entry. That forces you to lean into it and get close to the object. And that narrator starts in a regular tone. It’s kind of soothing, informative and inquisitive, and has a generally calming nature. Then it speeds up and you can move on. You haven’t lost my attention; I don’t feel like I have to sit here forever.

DB: One thing that struck me is how professional this is. Every element is super precise. The structure has nice sharp wood pieces, the phones have clean, new coiling, and each object is backed with nice fabric. Those elements make you give into the piece and focus on the story and the object.

NG: It’s one of those interesting moments where something so well executed falls into the background, and that’s its mark of success.

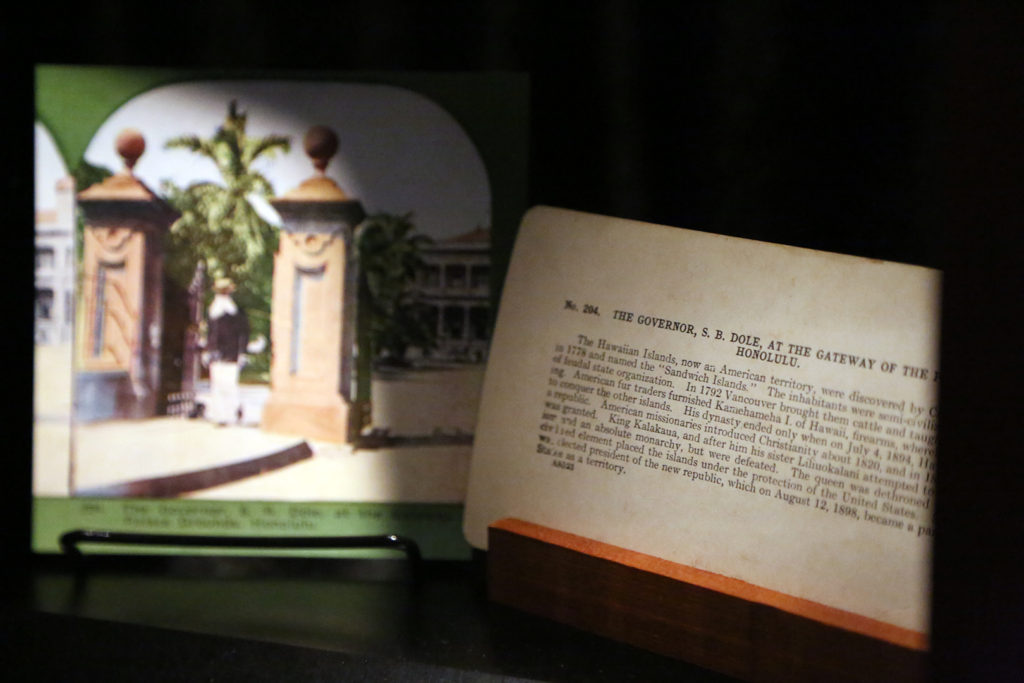

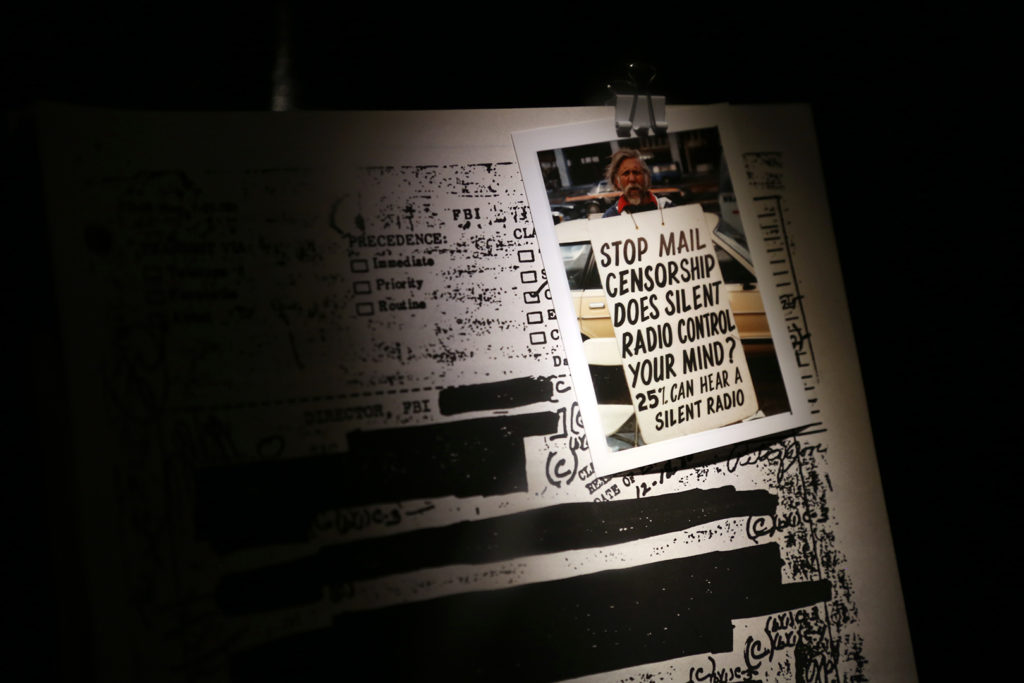

DB: There is a through line of government intervention and conspiracy in many of the stories. Secret aircraft, imperialist plots, UFOs….

NG: Scientology. Conspiracy is treated as a kind of magic. With the Sea-Monkeys and Scientology, you have rules and expectations that a person behind the curtain has set up to redirect your attention.

DB: That line between illusion and reality.

NG: It’s weird that I’m comparing an old pack of Sea-Monkeys to a Scientology E-meter, but in a lot of ways they are very similar.

NG: I really appreciated the puppet, which is a nice introduction to the room. It’s the only piece that has additional decoration, as it has a frame around the window and a title. As you pick up the phone, the narrator retells how he saw a puppet machine of a woman folding many paper planes, and that it was called “Flight Simulator.”

DB: Yeah, the text draws your eye to this piece and then, when you pick up the phone, the puppet starts to move. These actions create excitement right away. It feels a bit like magic, like anything can happen as you move to the following windows.

NG: As we entered, there were basically three starting options. First, the puppet window with text and a moving doll. Then there is essentially the opposite of that interaction—an extremely small piece of paper with a magnifying glass. Or you could start with a more traditional vignette where there are paper cutouts depicting an early museum setting. So, these three windows that meet you at the entrance are more in line with your expectations of an exhibit called the Cabinet of Ambiguities. Then as you go through, the scope broadens with a copy of FBI papers on a Pittsburgher or a window telling two different histories of how Hawaii came under U.S. control. It’s interesting how your expectations are manipulated—how you lose expectations.