I started saying it almost as soon as I moved here: “That’s Pittsburgh with an ‘H.'” It was the first time I had my own address, and relatives, friends, and anyone else who needed it were going to spell “Pittsburgh” right, dammit. I was born in New England and grew up on the West Coast, both within driving distance from a Pittsburg. But Pittsburg, New Hampshire and Pittsburg, California had nothing on the original Pittsburgh, the Pittsburgh of renown, our Pittsburgh. And neither had an “H.”

![]()

In 1890, Thomas Corwin Mendenhall decided to tackle a problem.

As the recently appointed superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey Office, the premier agency for standardizing the nation’s maps, charts, and weights and measures, Mendenhall presided over a government agency that just a few years prior had been placed under a watchful congressional eye due to swirling accusations of graft and favoritism. But Mendenhall’s predecessor Frank Manly Thorn had weathered these bureaucratic storms well. By firing embezzlers, streamlining operations, and ensuring on-time production of maps and charts, Thorn had fended off the threat that the office, one of the federal government’s earliest scientific agencies, would be dissolved or merged with the U.S. Geologic Survey or the Department of the Navy.

But a more externalized problem remained for Mendenhall—one concerning standardization. From mountains and waterways to cities and villages, it was considered critical to enact standard naming conventions for a growing, industrial country. Could both “La Fayette” and “Lafayette” coexist? Should names include hyphens, or apostrophes, or even German umlauts or Spanish tildes?

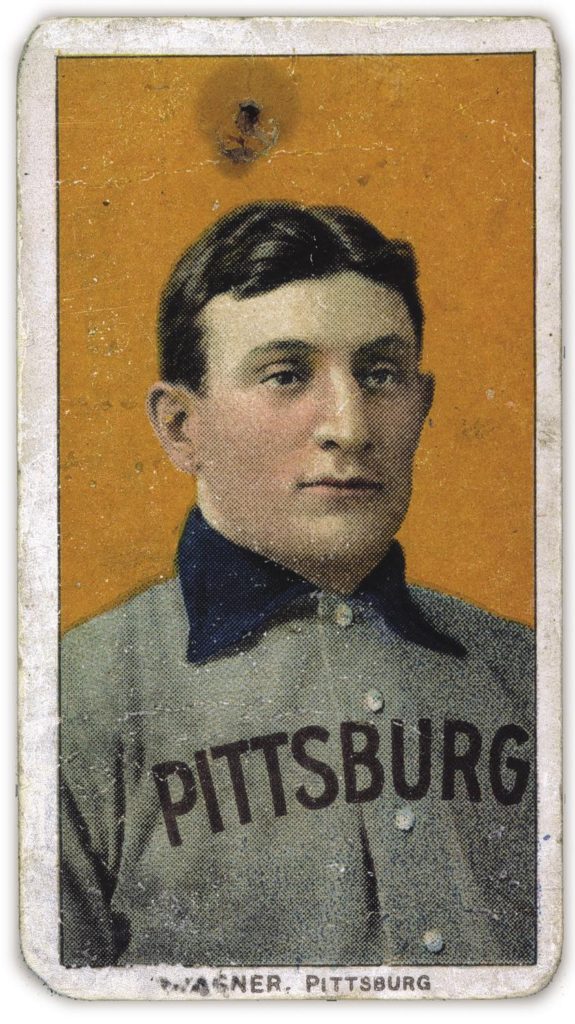

Pittsburgh exhibited its own quandary. Named for William Pitt the Elder and originally carrying the suffix “-bourgh,” it’s likely that the frontier town was pronounced “Pittsburra,” like the Scottish say “Edinburgh.” Soon, “Pittsburgh” became something of a dominant spelling, though examples of “Pittsburg” could be found as well. As Pittsburgh became an industrial center, this orthographic messiness had to be fixed.

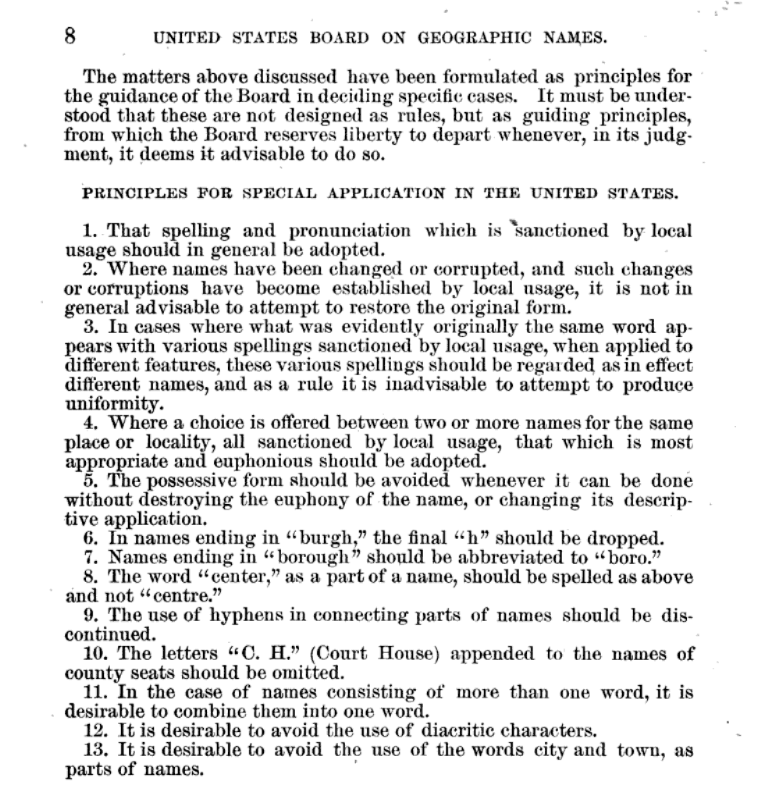

President Benjamin Harrison in 1890 gave Mendenhall the authority to establish the United States Board of Geographic Names, a board of ten geographers “to which may be referred any disputed questions of geographical orthography”—and whose decisions would be considered binding across all departments and agencies of the federal government. The next year, the board published its First Report, which outlined thirteen principles for place-naming. Principal 6 included this stipulation: In names ending in “burgh,” the final “h” should be dropped.

Pittsburghers were divided. Federal agencies, including the Post Office, were forced to adopt the change, but many local institutions, like the University of Pittsburgh or the Pittsburgh Gazette, refused.

This state of affairs lasted for two decades until, under pressure from attorney, newspaper publisher, and Pennsylvania Senator George T. Oliver, a Pittsburgh native, and William Hamilton Davis, Spanish-American veteran and Pittsburgh postmaster, the decision was reversed. On July 19, 1911, the U.S. Geographic Board wrote Senator Oliver a letter, capitulating:

Sir: At a special meeting of the United States Geographic Board held on July 19, 1911, the previous decision with regard to the spelling of Pittsburgh without the final H was reconsidered and the form given below was adopted:

Pittsburgh, a city in Pennsylvania (not Pittsburg).

July 19th, then, represents a day of victory. Pittsburgh’s “H” is more than just a particular spelling. It’s a symbol of pride and identity—we are “PGH” after all—and it’s a triumph of regional variety over standardization. We should recognize July 19th as a local holiday: H Day.

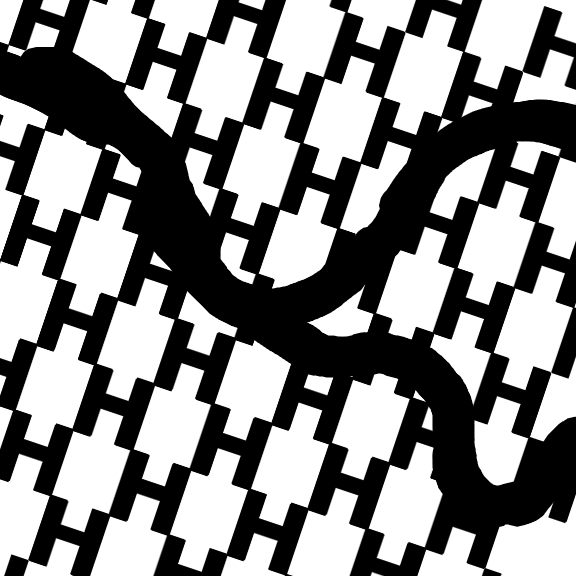

For me and my partner Rigel Richardson, H Day has become a celebration of all things Pittsburgh. When we first marked the occasion in 2011, the hundredth anniversary of the return of the H, we baked a cake using a local beer, and Rigel designed a cake pattern that incorporated the iconic geography of the city. We’re sharing our recipe below. On July 19th, join us in celebrating Pittsburgh’s H Day—and use the hashtag #hday to share it aht!

![]()

Pittsburgh Chocolate Stout “H” Cake

Tools you will need:

• Oven and stove

• Three 8-inch round cake pans (sides should be 2 inches high)

• Parchment paper

• Mixing bowls

• Double boiler (or a bowl simmering over water)

• Whisk

• Spatula

• Electric mixer

• Serving plate

• Printed PDF of the H Day pattern (see below)

Ingredients:

• 12 oz. stout (consider East End Brewing Co.’s Black Strap Stout for a local nod; otherwise Guinness or another dark stout)

• 1 cup unsalted butter (plus some extra to grease parchment paper)

• 7 oz. dark chocolate, chopped roughly

• 3 large eggs

• 2 egg yolks

• ¼ cup of Canola oil

• 1⅓ cups of sour cream

• 3 cups all-purpose flour

• 1 Tbsp. baking powder

• 1 Tbsp. espresso powder (or instant coffee)

• ¾ cup unsweetened cocoa powder (consider Penzeys Dutch Process cocoa powder for a local nod; otherwise any Dutch Process powder)

• 1 tsp. kosher salt

For the icing:

• 1 cup unsalted butter, softened

• 1 cup sour cream

• 4 cups dark chocolate chips, melted

• 4 cups powdered sugar

• ¼ cup bourbon

• ½ cup heavy cream

Preparation:

The icing takes 30 minutes at least to cool, so make it ahead of time.

In a bowl or stand mixer, beat the softened unsalted butter until creamy. Add the sour cream; beat until fluffy and light. Slowly add the melted chocolate, and mix until combined. Add in the powdered sugar, and mix until combined. Add in the bourbon and then the cream, one tablespoon at a time. Be sure to scrape the bottom of the bowl while mixing. Once ingredients are thoroughly combined, cool in a refrigerator for at least 30 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 350ºF.

Butter three 8-inch pans. Butter the parchment paper and line the pans.

In a double broiler (or in bowl over simmering water), whisk together dark chocolate and butter, stirring constantly. When just melted, add in the stout. Remove from heat.

In a bowl or stand mixer, beat together the sugar, eggs, and yolks until light and fluffy. Add in Canola oil and sour cream and beat until combined. Then slowly add the stout mixture and beat until evenly mixed.

In a separate bowl, whisk together flour, baking powder, espresso powder, cocoa powder, and kosher salt. Sprinkle over the wet ingredients, stirring continuously until combined into a batter.

Divide the batter among three prepared pans. Bake them about 22 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean. Remove the cakes and let cool for at least 10 minutes in the pan. Then remove them out of the pans and let cool for at least 20 minutes.

Stack the cakes on a serving platter, adding icing between each layer. Add a layer of icing on the top of the cake and the sides. Then, decorate the cake as you wish—download our official H Day PDF pattern here.

To Pittsburgh!